Test Pits Earthquake Forecasts Against Each Other

Everyone in an earthquake-prone area wants to know when the next big one might come, but temblors are not well understood, and there is a plethora of methods that forecast quake risk. So which one works best?

A test of seven different techniques that one day could reveal when quakes will occur could help narrow the field.

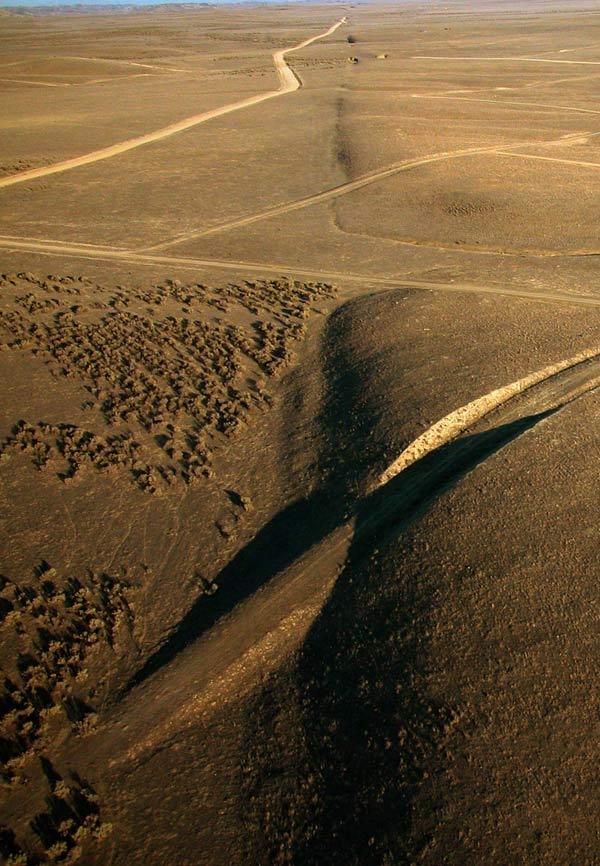

So far, reliable predictions of earthquakes do not appear possible in the short term — no early warning came with the 2004 Parkfield magnitude 6 quake in California, for instance, or even the massive magnitude 9 that rocked Japan earlier this year, despite it being one of the most seismically monitored areas on Earth. Still, quakes don't happen randomly in space and time, researchers note. Large ones prefer to occur where small ones do, and earthquakes on active faults happen semi-periodically over time.

Scientists have bandied about a number of different earthquake forecasting methods over the years. For instance, one technique might look at the magnitude and timing of small quakes to predict when larger ones might occur; another might examine geological evidence of ancient temblors to forecast when future ones might happen; still another might estimate how much stress is built up in faults to guess when they might rupture from the pressure.

To see which technique might work best, researchers were invited to submit forecasts of future quakes to the Regional Earthquake Likelihood Models (RELM) test, the first competitive analysis of such methods. The project was supported by the Southern California Earthquake Center, a consortium of 600 researchers funded by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Science Foundation.

Seven research groups submitted forecasts. The aim was to estimate the chances that earthquakes of magnitude 4.95 or higher would occur in more than 7,600 grids in and around California encompassing about 360,000 square miles (930,000 square kilometers) between 2006 and 2011. During this time, 31 earthquakes of the given magnitudes struck this area.

Of the seven techniques, a method known as "pattern informatics" scored as most reliable. This approach looks for anomalous increases and decreases in seismic activity, and if the number or intensity of these changes exceed a threshold based on past events, a given area gets flagged as a hot spot.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of the 22 grids stricken by quakes, the pattern informatics model flagged 17 as potential hot spots. For eight of these 17 this model had the highest certainty of an earthquake hitting of all the forecasting techniques, said researcher Donald Turcotte, a geophysicist at the University of California, Davis, who helped develop the model.

"We are not predicting the occurrence of a specific earthquake," Turcotte cautioned. "We are giving the relative risk of occurrence of earthquakes."

In the future, this research could be extended to other parts of the United States and to other countries, Turcotte told OurAmazingPlanet. He and his colleagues detailed their findings online today (Sept. 26) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus