How 'Hot Tub Rash' Bacteria Kills the Competition

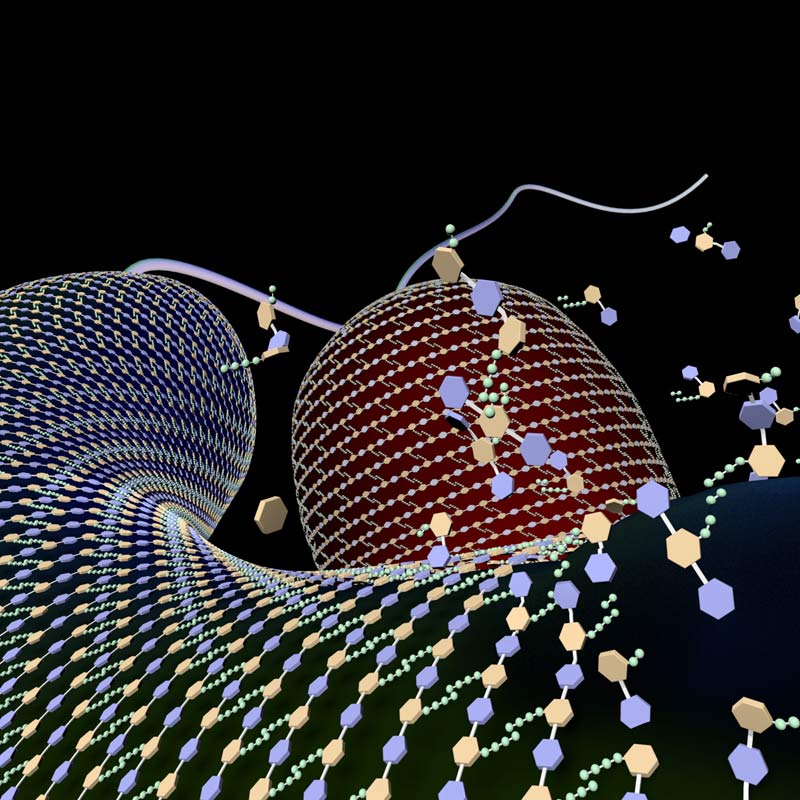

A common bacterium fights off competitors by injecting them with toxic proteins a using needle-like puncturing device, scientists have found.

This mechanism gives the bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an advantage in its environment and helps it in its quest to infect humans by eliminating other bacteria, including ones helpful for human health, according to the researchers.

"Competition among bacteria is brutal and fierce," said lead researcher Alistair Russell who is a National Science Foundation fellow at the University of Washington.

This research reveals another weapon in the arsenal microbes use to take out the competition. In this case, it is the machinery to deliver toxic proteins that attack the rival's protective barrier, called a cell wall causing the cell to burst. P. aeruginosa, meanwhile, protects itself so the toxins don't harm its own cell wall. It can also inactivate toxins injected by rivals. [Bacteria Think Ahead]

P. aeruginosais found in soil and other environments. It is generally not a problem for healthy people, but if it has the chance, P. aeruginosa can cause severe, even fatal, infections in immunocompromised people, those with cystic fibrosis, burn victims and others.

Although directed at other bacteria, this attack machinery makes it more of a menace to people, according to Russell.

"Pseudomonas is never going to encounter an infection site if it can't survive in the outside world," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This finding could be helpful to medicine because it could allow scientists to transplant this machinery to helpful bacteria, giving them a new weapon against disease causers. Scientists could also use knowledge of the machinery to create new antibiotics to prevent harmful P. aeruginosa from breaking through the barrier of normal, healthy bacteria, according to Russell.

The research appears in the July 21 issue of the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.