Dingoes Didn't Run Tasmanian Tigers Out of Australia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

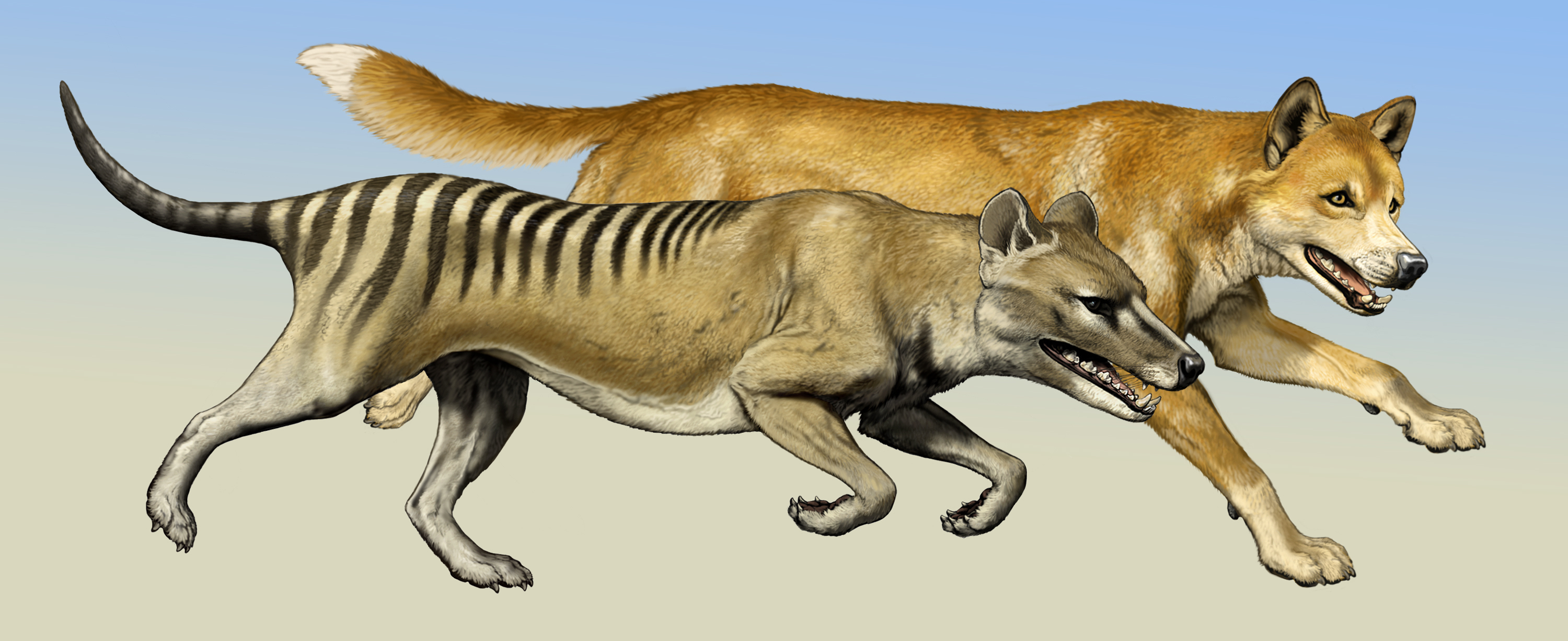

The extinct thylacine, more commonly known as the "Tasmanian tiger" or "marsupial wolf," hunted more like a cat than a dog, meaning the tiger moniker may be the more appropriate nickname.

The thylacine had the striped coat of a tiger, the body of a dog and like other marsupials (including kangaroos and opossums) carried its young in a pouch. These carnivores were last seen in Australia 3,000 years ago, having died out after the introduction of dingoes by humans. The last remaining populations were sheltered by their isolation on the island of Tasmania, surviving until the 1900s, when a concentrated eradication effort wiped the thylacine out.

Researchers hypothesized that the dingoes were a main cause of the thylacine decline in Australia, because the two species were in direct competition — using the same hunting strategies to hunt the same prey. [Top 10 Creatures of Cryptozoology]

"Dingoes are a species of wolves, they are runners," study researcher Borja Figuerido of Brown University said. "If the thylacines are ambushers, the hypothesis of the extinction of the thylacine outcompeted by dingoes is less probable."

Elbow joints connected to...

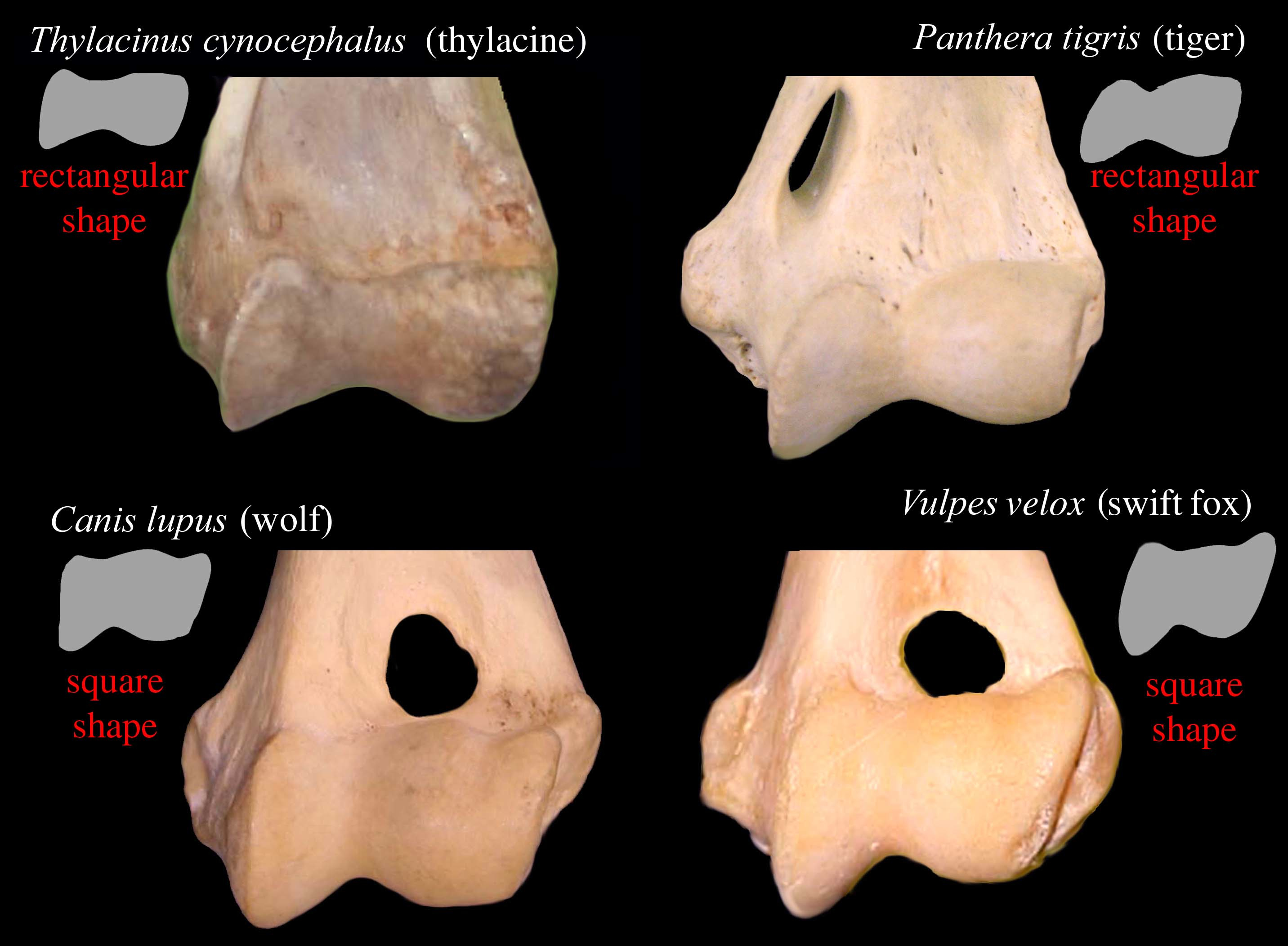

By looking at the elbow joint bones of the thylacine and 31 other mammals, the researchers noticed they resembled those of cats, which can rotate their paws upward to pounce and attack prey. Dogs and wolves don't have this rotation capability.

"These anatomical characters reveal something about the hunting strategies of the thylacine. They are more ambushers than previously suspected," Figueirido said. "Ambush predators usually manipulate the prey with the forearms, they have very good mobility. Running predators lack this ability, because the elbow is locked."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The limited rotation of their arm bones makes dogs and wolves (including dingoes) faster runners, which changed their hunting behaviors. Dogs and wolves hunt in packs, following their prey over longer distances. The researchers determined that the thylacine was more of a solitary, ambush-style predator, similar to cats.

Mammalian cousins

Marsupial mammals, found mainly in Australia and other areas of the Southern Hemisphere, are similar to placental mammals (such as humans, dogs and cats), but their evolution diverged from ours during the Cretaceous Period, the earliest example of a marsupial appearing about 125 million years ago.

The evolution of these two groups of mammals is an example of convergent evolution, where two separate groups in different locations evolve similar morphologies to deal with similar habitats. The thylacine was thought to be the marsupial equivalent, or ecomorph, of the wolf, with similar body size and eating habits.

Now, Figueirido said, "this designation will need to be revised."

The study was published today (May 3) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biology Letters.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescienceand on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus