Wiggle Room: Female Hormone Helps Sperm Meet Egg

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

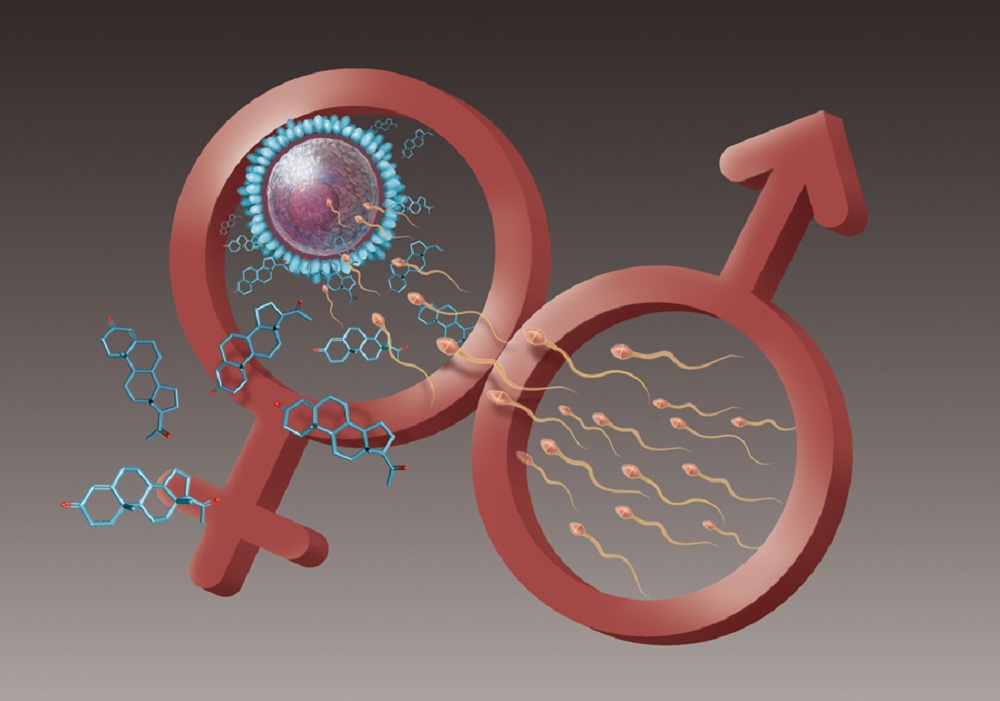

The female hormone progesterone kicks sperm into overdrive so they can make a fast beeline for the egg. Now scientists have figured out how: The hormone links up with a specialized protein that signals the sperm's tail to wiggle back and forth, helping propel the little guy to its target.

"To fertilize the egg, it [sperm] needs to penetrate the protective layers of the eggs," said study researcher Polina Lishko, of the University of California in San Francisco. "For this, it needs to move back and forth."

When progesterone binds the receptor referred to as catsper, it opens a channel in the membrane, sending a wave of calcium spiking down the sperm body, which causes this back-and-forth wiggling of its tail.

The research is outlined this week by Lishko's team in the journal Nature and in a second study, from a team led by U. Benjamin Kaupp at the Center for Advanced European Studies and Research in Germany.

Catsper's calcium affinity

"It's been known for more than 20 years that progesterone is a very significant stimulant of sperm's various functions," said Stephen Publicover, of the school of biosciences at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, who wrote an accompanying "News and Views" article in the journal issue.

Until now, however, scientists didn't know how the hormone and catsper interacted. The team looked at human sperm cells, measuring calcium flux that causes the tail movement. Their experiments showed that progesterone's interaction with catsper was critical to causing the wave of calcium, an integral part of getting sperm through the cells surrounding the egg. Past research had shown for mice, all that was needed was a change in pH, or acidity level. Humans need both pH changes and progesterone, it appears.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Progesterone doesn't activate mouse sperm cells — it's very specific to humans," Lishko told LiveScience. "When you study human fertility, you have to study it on the human sperm cells."

The researchers found that in human cells, progesterone opens catsper channels in the sperm and sends a wave of calcium to hyperactivate the tail. The result: Big swings of the sperm's tail, which are integral to getting it through the cells surrounding the egg. If it can't get through, the sperm never reaches the egg and can't fertilize it. Both humans and mice with nonfunctional catsper are infertile.

Contraceptive candidate

Because the catsper protein is only expressed in sperm cells, it's a perfect candidate to target with drugs, the researchers say. A drug that could incapacitate this channel or block it from binding with progesterone would stop the sperm from hyperactivating, and it couldn't break through to the egg to fertilize it.

"Catsper channel is a great target for developing new contraceptives, because it's expressed only on the sperm cells," Lishko said. (That means men and women could take it without impacting other reproductive functions or having the side effects of hormone-based drugs, like the pill.)

The research could also dig up other proteins involved in the sperm-to-egg process, leading to nonhormonal contraceptive drugs, Publicover said.

Lishko's team is now working to determine where the progesterone binds on the channel, and they hope to study patients with deficiencies in the catsper channel, to see how progesterone affects their sperm.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus