Scientists capture the world's deepest octopus on video. And it's adorable.

The octopus was found miles beneath the ocean surface.

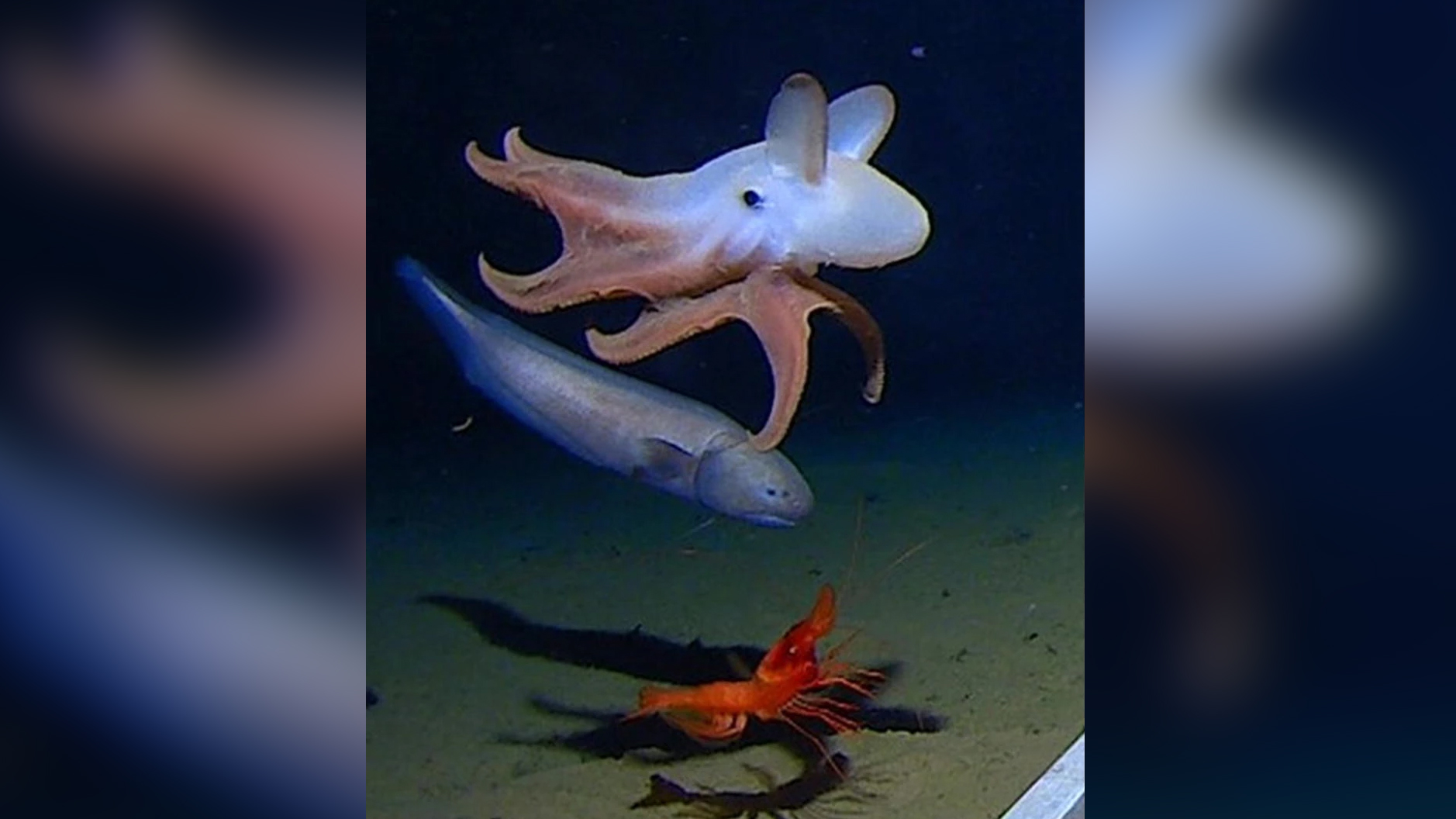

Explorers have captured video of the deepest-known octopus, revealing an adorably pudgy Dumbo octopus some 4.3 miles (6,957 meters) beneath the surface of the Indian Ocean swimming in what is called the hadal zone, where not even a drop of sunlight can penetrate.

The dumbo octopus (genus Grimpoteuthis), with its wee size and two relatively large fins that look like the eponymous Disney character's ears, is often called "the cutest octopus in the world," according to National Geographic. It's also one of the deepest-known octopuses, known to live more than 2 miles (3,200 m) below the ocean's surface.

The newfound creature — recorded more than a mile deeper than any octopus has ever been spotted before — and another Dumbo octopus dwelling 3.6 miles (5,760 m) below the surface were described in a new study, published May 26 in the journal Marine Biology.

Related: In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures

These discoveries were made last April during dives to the Java Trench — the deepest part of the Indian Ocean — as part of the Five Deeps expedition, in which a team of explorers dove to the deepest part of all of the world's oceans in a submersible and deployed landers, as previously reported by Live Science.

Dumbo octopuses are "cirrate" octopuses, meaning they have protrusions coming off their suckers called cirri, which have an unknown function, according to National Geographic.

These observations "unequivocally" identify cirrate octopuses as members of the hadal community, the authors wrote in the paper. The hadal zone is the deepest part of the ocean — typically deeper than 3.73 miles (6,000 m). But because both octopuses were observed in the same area, it's difficult to know whether such octopuses live this deep globally or if this was "the result of chance encounter with an abnormally deep population," the authors wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To live at such depths, these creatures' bodies would need to have somehow adapted to the extreme pressure of the deep sea, the chief scientist on the expedition, Alan Jamieson, who is also a senior lecturer at Newcastle University in the U.K. and the CEO of Armatus Oceanic, a deep-sea consultancy, told the BBC. "They'd have to do something clever inside their cells. If you imagine a cell is like a balloon — it's going to want to collapse under pressure. So, it will need some smart biochemistry to make sure it retains that sphere," he said.

The Indian Ocean is teeming with both familiar creatures such as starfish and sea cucumbers as well as unfamiliar ones. For instance, the Five Deeps explorers also captured a video of a strange gelatinous creature that looks like a balloon on a string, Live Science previously reported.

- In Photos: The Wonders of the Deep Sea

- Deep-Sea Creepy Crawlies: Images of Acorn Worms

- Images: Cameron's Dive to Earth's Deepest Spot

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.