Tubby 'tardigrade' crawls across sun's surface in spectacular images

The tardigrade-shaped blob was visible in an up-close solar view.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

No, tardigrades haven't colonized the sun. But a tardigrade-shaped speck on a solar mission's images recently led to some joking about the unlikely solar presence of a wee water bear.

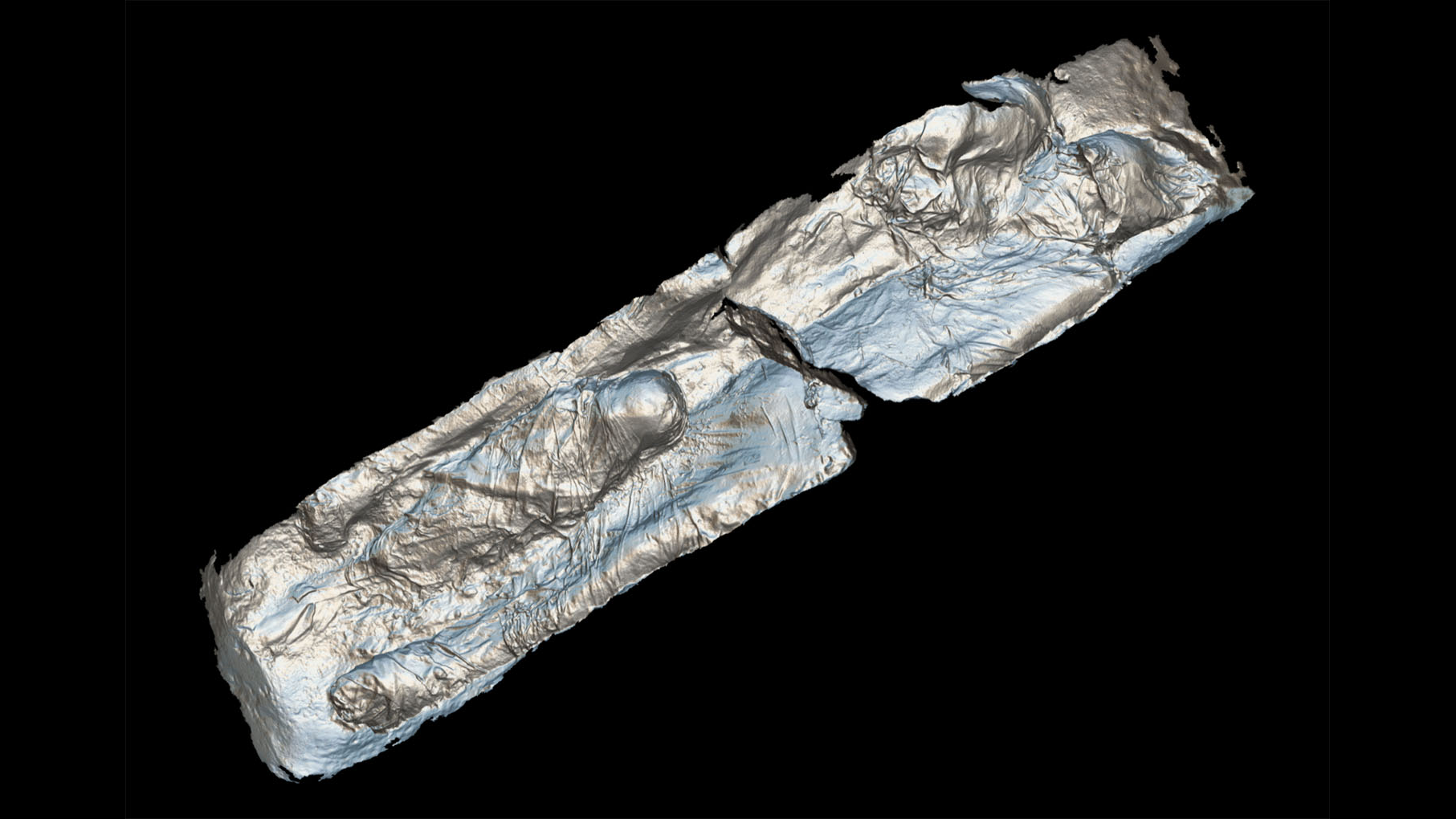

Today (July 16), when the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA unveiled the latest images captured by the agencies' Solar Orbiter mission, some sharp-eyed viewers were quick to point out a small, dark blotch on the left-hand side in one of the image sequences. David Berghmans, a principal investigator for the Solar Orbiter and Head of Scientific Service Solar Influences Data Analysis Center at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, noted during a news conference that the blob resembled a tardigrade: tubby, eight-limbed microscopic animals that are known for their indestructibility.

But the dark blob was actually an image flaw that happened to have a tardigrade-like shape, Berghmans explained.

Related: 8 reasons why we love tardigrades

Solar Orbiter launched in February, carrying imaging equipment to capture views of our nearest star that will zoom in closer than any seen before, Live Science sister site Space.com reported. The mission's first images have already revealed intriguing new solar features, which gobsmacked scientists have nicknamed with "crazy names" such as "campfires and dark fibrils and ghosts," Berghmans said at the news conference.

And when Solar Orbiter researchers spotted an oval shape that appeared to be "crawling" over some of the images, they referred to it as "a little tardigrade" and "our extra biology experiment," Berghmans said.

"But in fact, it's a sensor defect," he said. "In future processing when we further optimize this, this will be cleaned up and interpolated from nearby pixels. But for the moment, it's still clearly visible."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The "tardigrade" looks like it's moving because the original images were "a bit shaky," which the researchers corrected with software. But after that correction, fixed parts of the image — such as defects in the detector — started moving independently, which is why the tardigrade appeared to crawl, Berghmans said.

On Twitter, Jack Jenkins, a postdoctoral researcher studying solar prominences at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium, mentioned the tardigrade "hitchhiker," suggesting that the Solar Orbiter mission adopt the water bear as a mascot (mission representatives had not replied to the tweet by the time of this story's publication).

Anyone from @ESASolarOrbiter @EuiTelescope @long_daithi @MihoJnvr @asubsetofdaves fancy making the tardigrade the official mascot if this is true? 😍☺️ https://t.co/3IH1Q6KrsuJuly 16, 2020

Tardigrades are unexpectedly hardy for such small creatures. They can resist extreme cold and heat; they survive exposure to radiation, crushing pressure and the vacuum of space; and they can revive after spending years in a dried-out form known as a tun state.

Despite their hardiness, not even tardigrades could survive a close encounter with the sun, where surface temperatures can reach 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius). However, tardigrades have been sent to the moon — and some tardigrades may still be there right now. On April 11, 2019, the Israeli lunar lander Beresheet crashed on the moon, possibly scattering a payload that included thousands of tardigrades in a tun state.

But whether any of those dried-out tardigrades survived the crash remains unknown, Live Science previously reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus