Watch the 1st X-class solar flare of 2024 erupt from the sun in explosive fashion

An X-class flare, the most powerful type of solar flare, erupted from the sun on Feb. 9, 2024. Lucky for us, Earth wasn't in the direct firing line.

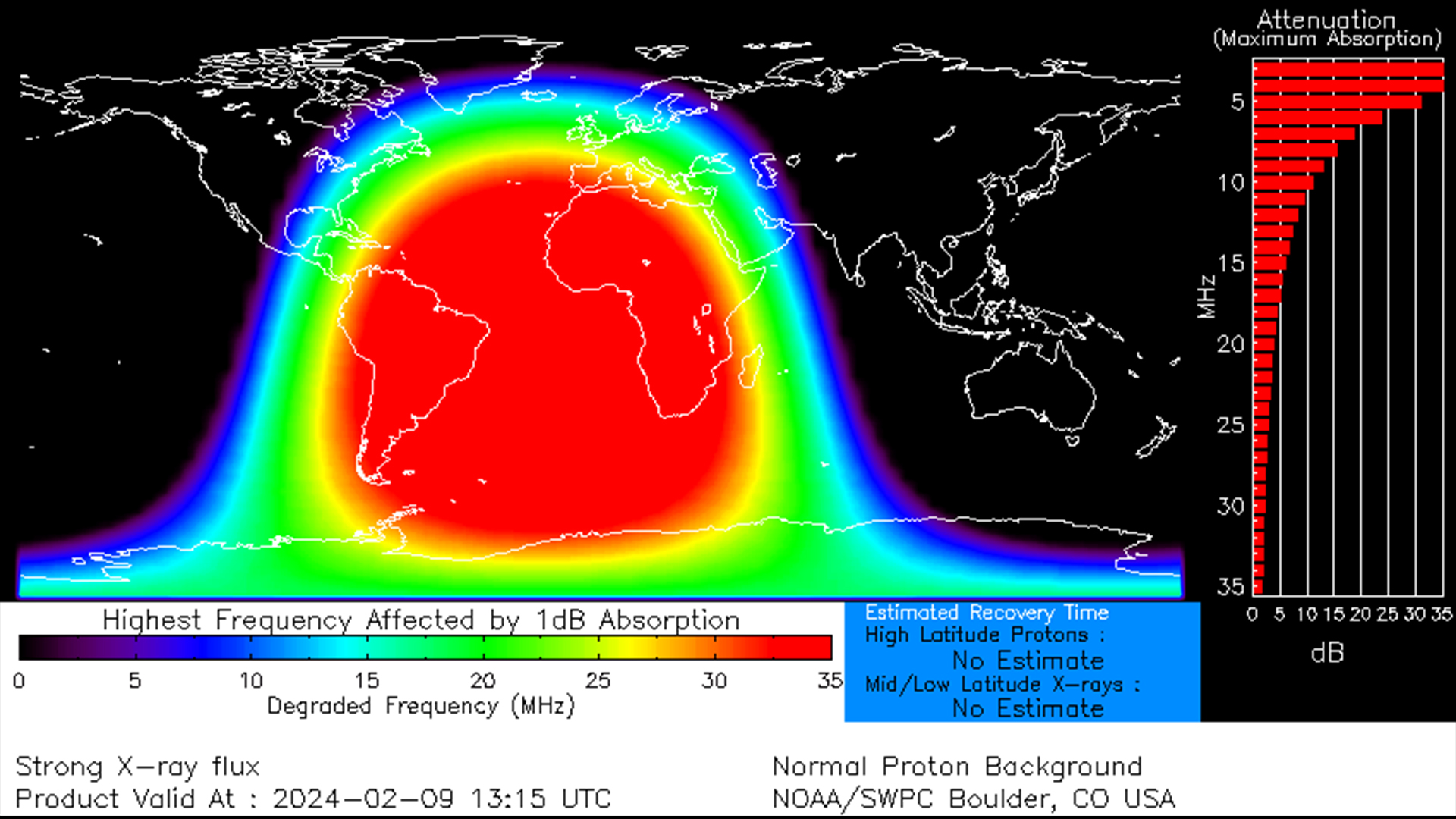

The sun unleashed a powerful X-class solar flare on Friday (Feb. 9), peaking at 8:10 a.m. (1310 GMT) and triggering shortwave radio blackouts across South America, Africa and the Southern Atlantic.

The solar flare erupted from sunspot AR3576 — the same sunspot that put on a fiery show on Feb. 5 with an M-class flare and plasma eruption.

Luckily for us, the sunspot moved beyond the sun's limb yesterday (Feb. 8), placing Earth outside of its direct firing line. "Goodness knows how big this flare would have been if it had happened this side of the sun," solar physicist Keith Strong wrote in a post on X.

The monstrous solar flare was accompanied by a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a large release of plasma and magnetic field from the sun.

"There was a clear eruption with a coronal wave suggesting a very fast CME to the west, " said heliophysicist Alex Young in a post on X.

If a CME hits Earth it can cause disturbances to our magnetic field and lead to geomagnetic storms which can be troublesome for Earth-orbiting satellites but a delight to aurora chasers on the hunt for dramatic displays.

Due to the location of the sunspot so far south, it is unlikely that any CME from sunspot AR3576 will strike Earth directly; it is more likely to pass straight under us.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While we may not be in the direct firing line, it doesn't mean we are not affected. The X-flare caused extensive radio blackouts due to the strong pulse of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation sent barrelling toward Earth at the time of the eruption. Traveling at the speed of light, the radiation reached Earth in just over eight minutes and ionized the upper layer of Earth's atmosphere — the thermosphere — triggering shortwave radio blackouts on the sun-lit portion of Earth at the time including South America, Africa and the Southern Atlantic.

Solar flares are triggered when magnetic energy builds up in the solar atmosphere and is released in an intense burst of electromagnetic radiation. They are categorized by size into lettered groups, with X-class being the most powerful. Then there are M-class flares that are 10 times smaller than X-class flares, then C-class, B-class and finally A-class flares which are too weak to significantly affect Earth. Within each class, numbers from 1 to 10 (and beyond, for X-class flares) denote a flare's relative strength. The recent flare clocked in at X.3.38 according to Spaceweatherlive.com using data from NASA's GOES-16 satellite.

The sun is becoming incredibly active as it approaches the most active part of its approximately 11-year solar cycle known as the "solar maximum." Just yesterday (Feb. 8) a giant sunspot crackling with M-class solar flares turned to face Earth. The sunspot — AR3576 — is so big it was seen by the Perseverance Rover on the surface of Mars. Could we see a similarly powerful X-flare eruption from the "Martian sunspot"? Only time will tell.

Solar and space weather scientists are monitoring the sun carefully as energetic solar flares and CMEs can be problematic for satellites in space and electronic technology here on Earth. Scientists at NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center analyze sunspot regions daily to assess the threats. The World Data Center for the Sunspot Index and Long-term Solar Observations at the Royal Observatory of Belgium also tracks sunspots and records the highs and lows of the solar cycle to evaluate solar activity and improve space weather forecasting. NASA also has a fleet of spacecraft — known collectively as the Heliophysics Systems Observatory (HSO) — designed to study the sun and its influence on the solar system, including the effects of space weather.

Originally published on Space.com.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 as a reference writer having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus