Ominous 'Chamaeleon' is hiding a stellar secret: Space photo of the week

The Dark Energy Camera captured glowing nebulae in the Chamaeleon I star-forming region, illuminating the dense clouds with newborn starlight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What it is: The Chamaeleon I star-forming cloud

Where it is: 522 light-years away, in the constellations Chamaeleon, Apus, Musca, Carina and Octans

When it was shared: June 10, 2025

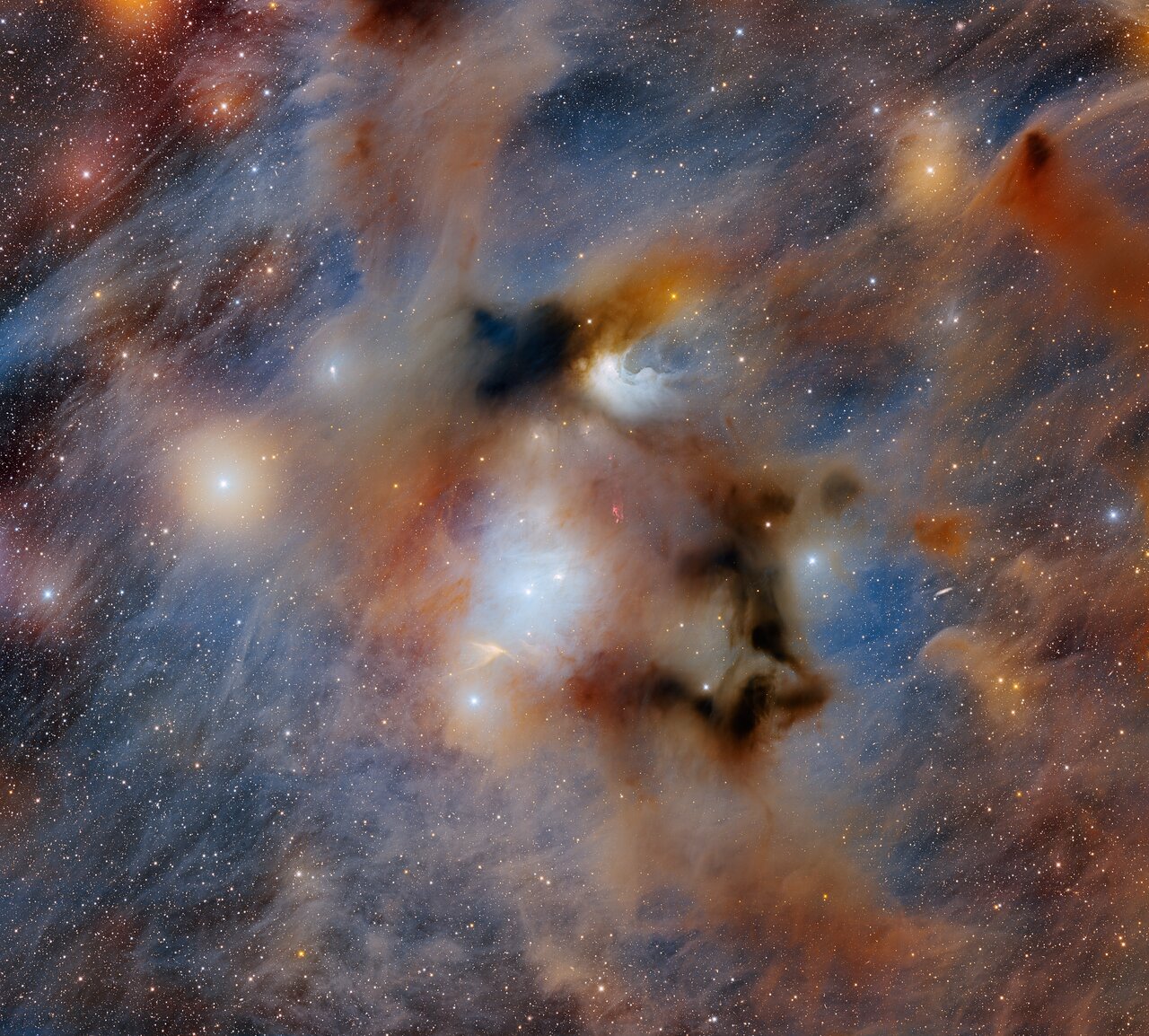

Stars form within dark molecular clouds of gas and dust called nebulae, but it's rare to capture these stellar nurseries clearly. A dramatic new image from the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) in Chile unveils the Chamaeleon I dark cloud — the closest such place to the solar system — in unprecedented detail.

The dark patches exposed in the new image give Chamaeleon I an ominous look, but within the thick veils of interstellar dust are pockets of light created by newly formed stars. Chamaeleon I is approximately 2 billion years old and is home to around 200 to 300 stars.

Those young stars, now emerging from swirling gaseous plumes, are lighting up three nebulae — Cederblad 110 (at the top of the image), the C-shaped Cederblad 111 (center) and the orange Chamaeleon Infrared Nebula (bottom). In astronomy, the word "nebula" is used to describe a diverse range of objects. It was initially used to describe anything fuzzy in the sky that wasn't a star or a planet, and it also refers to planetary nebulae, shells of gas ejected from dying stars.

Related: 28 gorgeous nebula photos that capture the beauty of the universe

However, these three are reflection nebulae, which glow brightly only because they're illuminated by starlight. That's in contrast to the famous Orion Nebula, which emits its own light because the intense radiation of stars within or near the nebula energizes its gas, according to NASA.

Chamaeleon I is just one part of the expansive Chamaeleon Cloud Complex — imaged in 2022 by the Hubble Space Telescope — which includes the smaller Chamaeleon II and III clouds. Chamaeleon I has been imaged many times before, most recently by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2023.

What makes this new image stand out is its spectacular detail. Mounted on the National Science Foundation's Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, DECam's 570-megapixel sensor reveals an intriguing faint red path of nebulosity between Cederblad 110 and Cederblad 111. Formed when streams of gas ejected by young stars collided with slower-moving clouds of gas, they're known as Herbig-Haro objects and are embedded throughout Chamaeleon I.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For more sublime space images, check out our Space Photo of the Week archives.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus