See Mercury's frigid north pole in extraordinary new images from the BepiColombo spacecraft

A joint Japanese-European mission to Mercury just made its sixth flyby of the planet, revealing stunning close-ups of the permanently shadowed craters at Mercury's north pole.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

New photos of Mercury's mysterious north pole reveal a glimpse of the permanently dark, frigid craters that may hold ice dozens of feet thick, even though Mercury is the closest planet to the sun.

Mercury's surface can reach a blistering 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius) during the day, according to NASA. But the planet lacks an atmosphere to hold that heat in — so, on Mercury, dark equals cold. At night, temperatures can plunge to minus 290 F (minus 180 C). The planet's north pole is pockmarked by craters whose bottoms are always in shadow. Research has shown that these crater bottoms likely contain thick deposits of water ice.

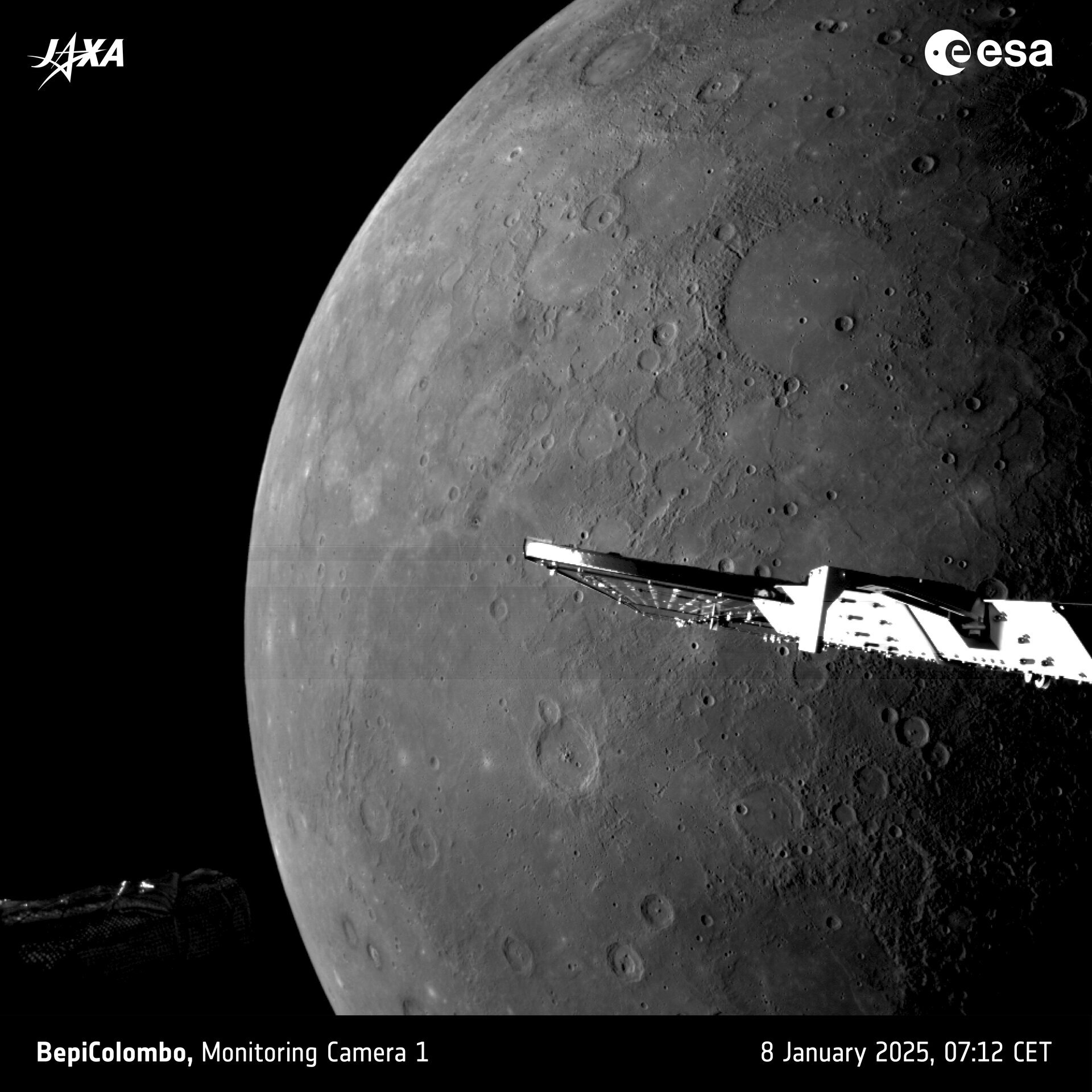

The new images of these cold craters come courtesy of BepiColombo, a joint mission of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and the European Space Agency (ESA). The BepiColombo spacecraft will start orbiting Mercury in 2026. Right now, it's conducting a series of flybys of the planet to get into position for that orbit. On Jan. 8, one of those flybys brought the craft within 183 miles (295 kilometers) of the planet's surface. BepiColombo also passed right over Mercury's north pole.

Lands of perpetual shadow

The spacecraft sent back a series of stark images, including photos of the perpetually shadowed Prokofiev, Kandinsky, Tolkien and Gordimer craters. It also snapped photos of Borealis Planitia, where massive lava flows 3.7 billion years ago created a smooth plain, according to ESA. The pictures show Mercury's biggest impact crater, as well as a mysterious, boomerang-shaped lava flow.

Related: 10 jaw-dropping space photos that defined 2024

Ancient lava deposits form bright patches on Mercury's surface.

A view of Mercury's northern, sunlit side.

A third image shows Nathair Facula, a light-colored region left behind by volcanic eruptions in the planet's past. Younger areas on Mercury are lighter, according to ESA; though researchers don't know what the planet's surface is made of, it clearly darkens with age. Near Nathair Facula is another bright spot, Fonteyn crater, which formed in an impact 300 million years ago.

When the BepiColombo spacecraft enters Mercury's orbit, it will separate into two orbiters that will focus on the planet's north and south poles. Among the questions it will probe, according to ESA, is whether water ice really exists in the planet's craters and what Mercury's surface is actually made of.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus