Our universe is merging with 'baby universes', causing it to expand, new theoretical study suggests

The universe is expanding faster and faster, but not all scientists agree that dark energy is the cause. Perhaps, instead, our universe keeps colliding with and absorbing smaller 'baby universes,' a new theoretical study suggests.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Our universe is expanding at an ever-accelerating rate — a phenomenon that all theories of cosmology agree upon but none can fully explain. Now, a new theoretical study offers an intriguing solution: Perhaps our universe is expanding because it keeps colliding with and absorbing "baby" parallel universes.

Studies of the cosmic microwave background, the afterglow of the Big Bang, have revealed that our universe is experiencing accelerated expansion. For this observation to fit with the main theory of cosmic evolution — called the Standard Cosmological Model — physicists assume that the universe is filled with an enigmatic substance dubbed dark energy that drives the expansion.

But this elusive form of energy does not manifest itself in any other way, leading many astrophysicists to question its existence and explore the possibility of an alternative cause for the universe's expansion.

In a new study published Dec. 12, 2023 in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, scientists proposed the idea that the expansion of the universe may be driven instead by constantly merging with other universes.

"The main finding of our work is that the accelerated expansion of our universe, caused by the mysterious dark energy, might have a simple intuitive explanation, the merging with so-called baby universes, and that a model for this might fit the data better than the standard cosmological model," lead study author Jan Ambjørn, a physicist at the Copenhagen University told LiveScience in an email.

Swallowing cosmic 'babies'

While the idea of multiple universes interacting with ours isn't new, this study develops a mathematical model to explore the hypothetical impact of this on the evolution of our universe. The researchers' calculations showed that merging with other universes should increase the volume of our universe, which could be perceived by our instruments as an expansion of the universe.

The scientists also computed the rate of expansion of the universe using their theory, and their calculations more closely fit with observations of the universe than the traditional Standard Cosmological Model, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: After 2 years in space, the James Webb telescope has broken cosmology. Can it be fixed?

The authors' theory also addresses the problem of cosmological inflation — the mysterious super-rapid expansion that occurred in the early moments of the universe.

Physicists have previously proposed that this expansion was caused by "the inflaton" — a hypothetical field that drove ultra-rapid expansion in the first milliseconds after the Big Bang. But in the new study, the authors suggest this super-rapid early expansion could have been caused by our young universe being absorbed by a larger universe.

"The fact that the Universe has expanded … in a very short time, invites the suggestion that this expansion was caused by a collision with a larger universe, [that is] it was really our Universe which was absorbed in another 'parent' universe," the researchers wrote in their paper. "Since we have presently no detailed description of the absorption process, it is difficult to judge if such a scenario could take place in a way that would actually solve the problems inflation was designed to solve, but one interesting aspect of such a scenario is that there is no need for an inflaton field."

The scientists suggested that, after being absorbed, our newly enlarged universe then continued to collide with other “baby universes” and incorporate them as well.

Although the authors' theory enables us to solve some important problems of modern cosmology, only observational data can validate their hypothesis. Many experiments are currently being carried out to study the properties of the microwave background, so scientists may be able to answer these fundamental questions in the near future.

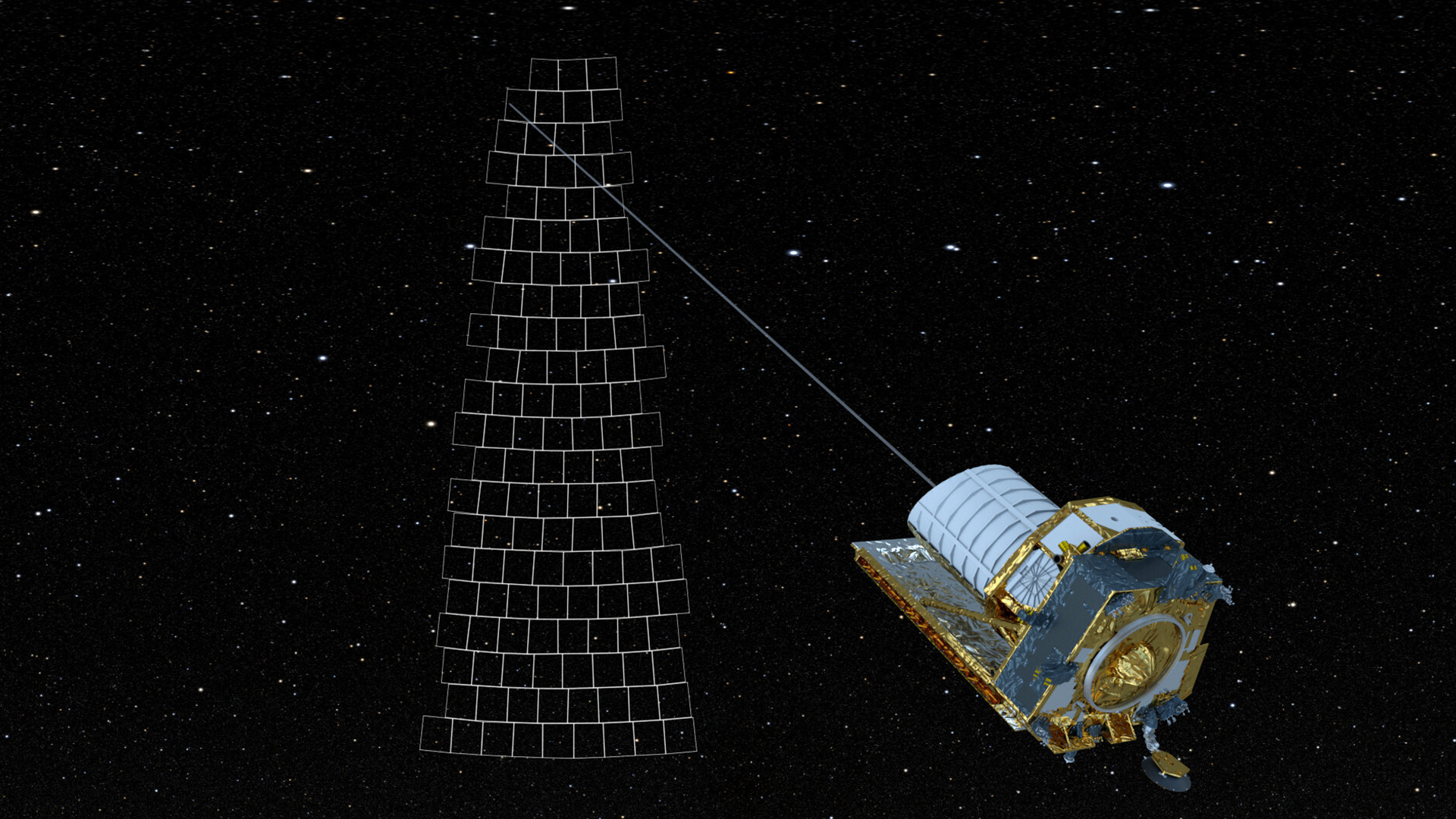

"Our late time expansion of the Universe is different from the standard cosmological predictions and we believe that observations from the Euclid telescope and the James Webb telescope will settle which model is best describing the present time expansion of our Universe," Yoshiyuki Watabiki, a physicist at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, told Live Science.

Andrey got his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in elementary particle physics from Novosibirsk State University in Russia, and a Ph.D. in string theory from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. He works as a science writer, specializing in physics, space, and technology. His articles have been published in AdvancedScienceNews, PhysicsWorld, Science, and other outlets.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus