Scientists reveal largest map of the universe's active supermassive black holes ever created

A massive new 3D map of space includes more than 1 million supermassive black hole-powered quasars, which are among the brightest objects in the universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers have unveiled a moving 3D map of supermassive black holes that covers the largest volume of our universe ever charted.

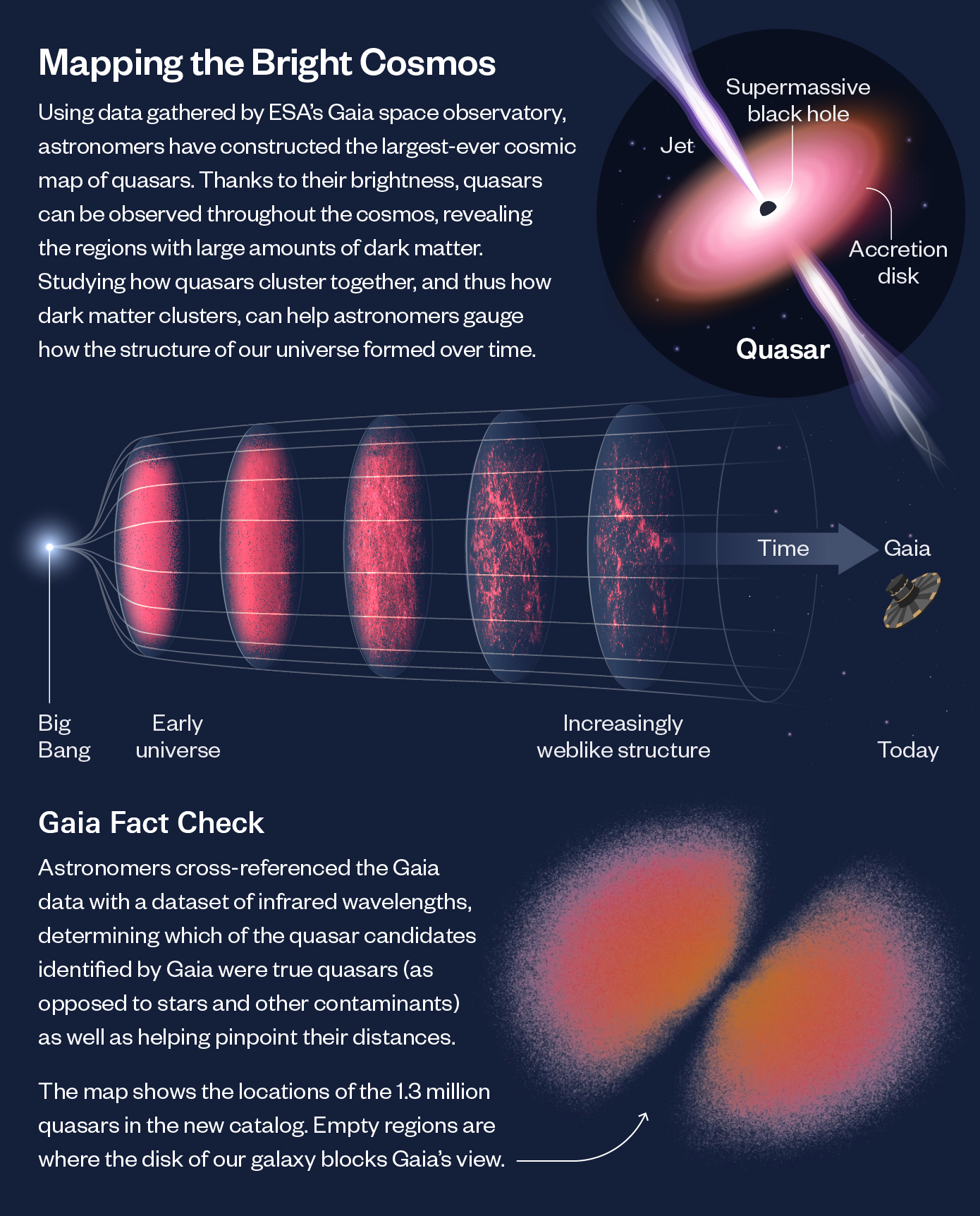

The map is made up of 1.3 million quasars, which are cores of active galaxies powered by supermassive black holes and some of the brightest cosmic objects in existence.

The light emitted by quasars comes from the supermassive black hole's gravitational pull on nearby clouds of gas, according to a statement released by the Simons Foundation in New York, which funds and supports research in science and mathematics. As friction heats up these clouds, they can form a bright, fast-moving disk that occasionally sprouts powerful jets of light.

The new map, called Quaia, is a catalog of quasars based on data collected by the European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope, among other sources. It appears in a new study published Monday (March 18) in The Astrophysical Journal.

"This quasar catalog is different from all previous catalogs in that it gives us a three-dimensional map of the largest-ever volume of the universe," map co-creator David Hogg, an astrophysicist at New York University and senior research scientist at the Simons Foundation's Flatiron Institute, said in the statement.

"It isn't the catalog with the most quasars, and it isn't the catalog with the best-quality measurements of quasars, but it is the catalog with the largest total volume of the universe mapped," Hogg added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers can learn a lot from quasars. Their evolution is intertwined with that of their host galaxies, so studying them gives scientists insight into the mysteries of how supermassive black holes grow and how massive galaxies form, according to the study.

Galaxies with quasars are also surrounded by dark matter — an invisible substance that is thought to comprise 85% of the universe's total matter — which provides researchers with an opportunity to learn more about this enigmatic substance, including how it clumps together, according to the statement. The standard model of cosmology suggests that these clumps influence the distribution of regular matter across the universe.

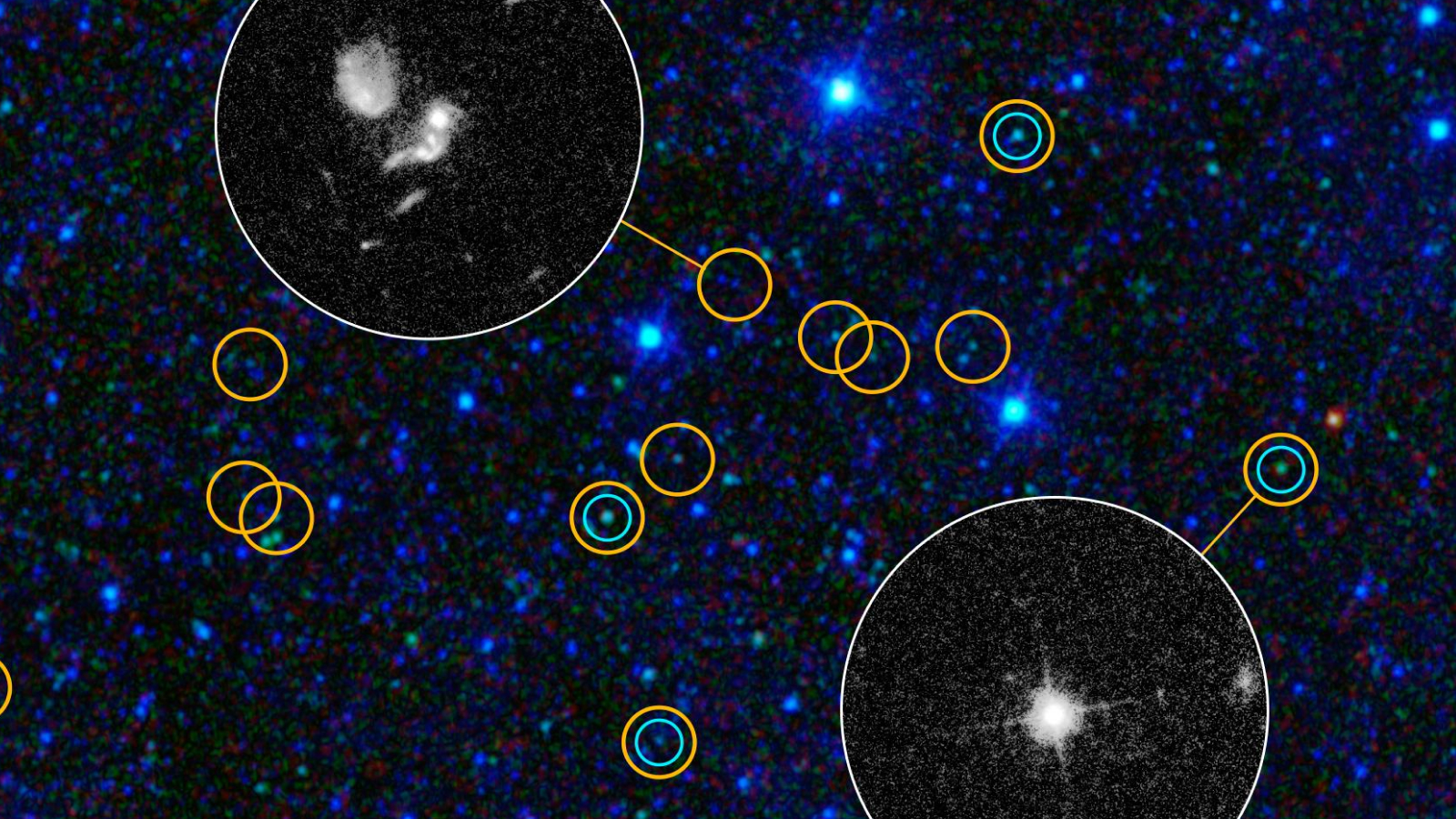

To chart their map, the team combined data from Gaia's third data release from June 2022, which flagged more than 6 million quasar candidates, with data from NASA's Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

The Gaia space telescope has been mapping the Milky Way since it launched in 2013. While its mission is focused on our galaxy, the telescope also records objects outside of the Milky Way, including quasars, according to the statement.

"We were able to make measurements of how matter clusters together in the early universe that are as precise as some of those from major international survey projects — which is quite remarkable given that we got our data as a 'bonus' from the Milky Way-focused Gaia project," said lead author Kate Storey-Fisher, a postdoctoral researcher at the Donostia International Physics Center, a research institution in Spain.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus