'Baby quasars' spotted by James Webb telescope could transform our understanding of monster black holes

Scientists think that by studying a cluster of "baby quasars," they can get a better understanding of supermassive black holes in the early universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

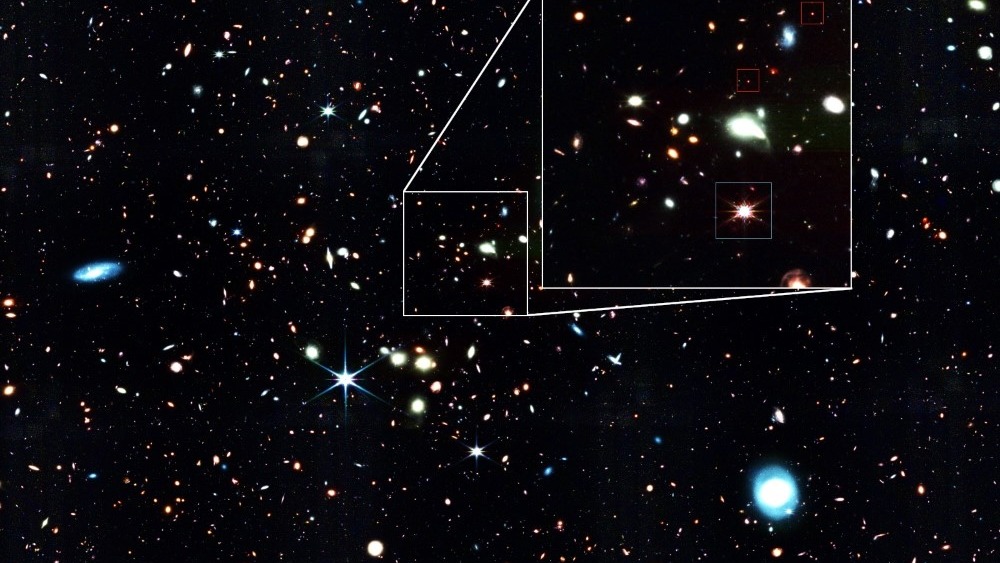

A cluster of faint, red dots lurking in the farthest reaches of the universe could change our understanding of how supermassive black holes (SMBHs) form.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) coincidentally spotted the specks, which astronomers say are actually "baby quasars," while studying an unrelated faraway quasar called J1148+5251.

Quasars are extremely bright objects powered by actively feeding supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. The target quasar emitted its light approximately 13 billion years ago — less than a billion years after the Big Bang, according to a study published Thursday (March 7) in The Astrophysical Journal.

While these mysterious spots had been previously recorded by the Hubble Space Telescope, it wasn't until scientists viewed them using the far more powerful JWST that they could finally distinguish them from normal galaxies, according to a statement.

"The JWST helped us determine that faint little red dots … are small versions of extremely massive black holes," lead study author Jorryt Matthee, an assistant professor of astrophysics at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, said in the statement. "These special objects could change the way we think about the genesis of black holes."

Related: 8 stunning James Webb Space Telescope discoveries made in 2023

Analyzing these tiny dots, which are tinged red by clouds of dust obscuring their light, required JWST's powerful infrared camera. By studying the different wavelengths of light emitted by the dots, the researchers determined that each one appeared to be a "very small gas cloud that moves extremely rapidly and orbits something very massive like an SMBH," Matthee said. In other words — a young quasar.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The dots don't seem out of place in the early universe, but they may be growing into "problematic quasars" — ultra-monstrous black holes that appear too massive to exist at such early epochs of the universe, the researchers said.

Astronomers using JWST have already uncovered many of these problematic black holes and struggle to explain them with current theories of cosmology.

"If we consider that quasars originate from the explosions of massive stars — and that we know their maximum growth rate from the general laws of physics, some of them look like they have grown faster than is possible," Matthee said. "It's like looking at a five-year-old child that is two meters [6.5 feet] tall. Something doesn't add up."

The researchers hope further study of these newly discovered "baby quasars" could help reveal how these problematic black holes grow so big, so fast.

"Studying baby versions of the overly massive SMBHs in more detail will allow us to better understand how problematic quasars come to exist," Matthee said.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus