Brightest black hole ever discovered devours a sun's-worth of matter every day

A distant quasar that was initially mistaken for a star is actually one of the brightest and fastest-growing black holes ever seen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

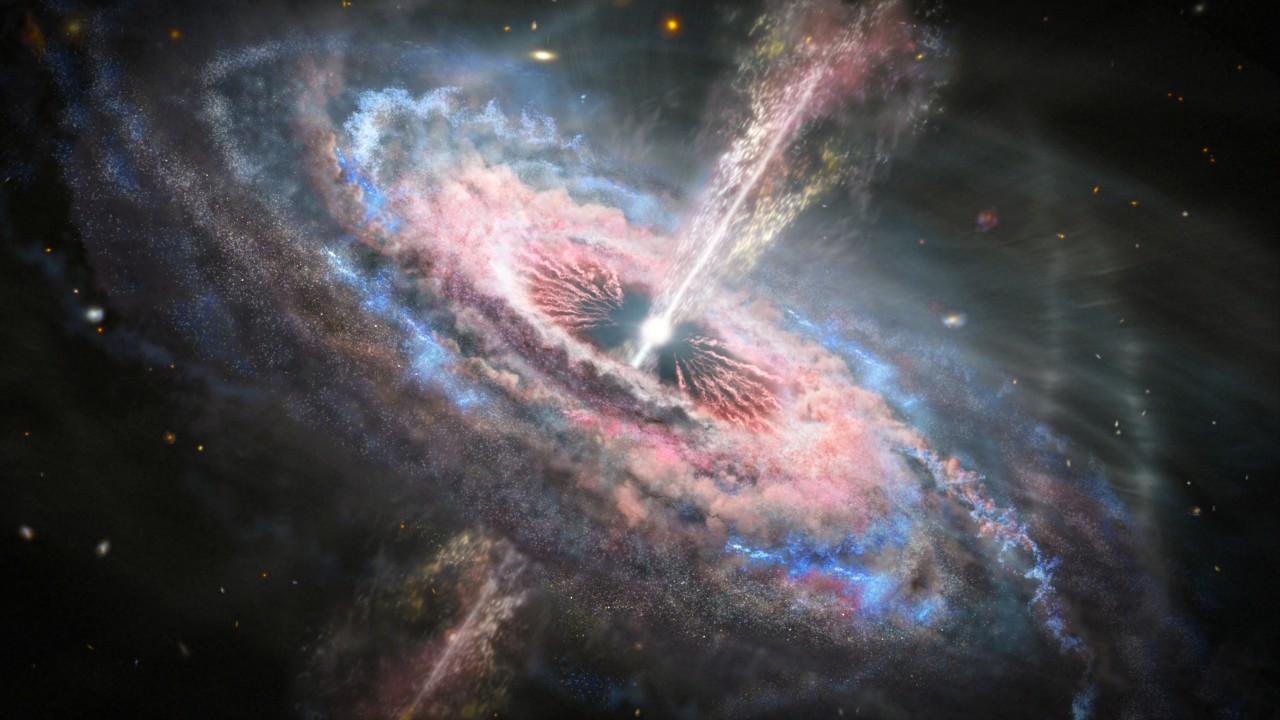

Scientists have spotted the brightest and fastest-growing quasar ever seen — a monster black hole that's devouring a sun's-worth of material every day.

The brightly burning object, named J0529-4351, weighs between 17 billion and 19 billion solar masses and is located 12 billion light-years from Earth — meaning it dates to a time when the universe was only 1.5 billion years old.

Related: James Webb telescope discovers the oldest, most distant black hole in the universe

Black holes are born when giant stars collapse in on themselves, and they grow by devouring all they encounter — be it gas, dust, stars, planets or other black holes.

Friction can cause the material spiraling into the maws of these gluttonous space-time ruptures to heat up, which emits light that can be detected by telescopes, turning them into so-called active galactic nuclei (AGN). The most extreme AGNs are quasars — supermassive black holes that are billions of times heavier than the sun and shed their gaseous cocoons with light blasts trillions of times more luminous than the brightest stars.

The quasar initially showed up in a 2022 survey by the European Space Agency's Gaia spacecraft, which has been mapping the positions and movements of the Milky Way's roughly 2 billion stars. However, as quasars often burn at least as brightly as stars, J0529-4351 was initially misidentified as one. (The word quasar itself is short for "quasi-stellar," because the two types of objects look so similar when seen through most telescopes.)

After searching for potentially misidentified black holes in the survey, the researchers behind the new study, which they published Feb 19 in the journal Nature, found J0529-4351 hiding in plain sight. Further observations by the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in the Atacama Desert confirmed that the bright object is a gigantic quasar, not a star.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By measuring the quasar’s perceived brightness and adjusting for its distance from Earth, the researchers estimated that the object was burning with the power of roughly 50 trillion suns (or 10^41 Watts).

This intense burn is owed to the fact that J0529-4351 is so big and consuming material so fast that it is very close to the Eddington limit — an upper limit on how bright an object can be given its size, according to the study authors.

The researchers hope that by studying the monstrous object they can both learn how quasars grew to such inexplicable sizes, as well as get better at distinguishing the monsters from among the brightest stars.

"Although their luminosity implies rapid growth, their existence is hard to explain," the researchers wrote in the paper. "When black holes start from the remnant of a stellar collapse and grow episodically within the Eddington limit, they are not expected to reach the evident masses in the time from the Big Bang to the epoch of their observation, which has triggered a search for alternative scenarios."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus