Gene mutation that helps make 'toy' dog breeds so small existed in wolves 54,000 years ago

It existed long before humans started breeding the cute canines.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

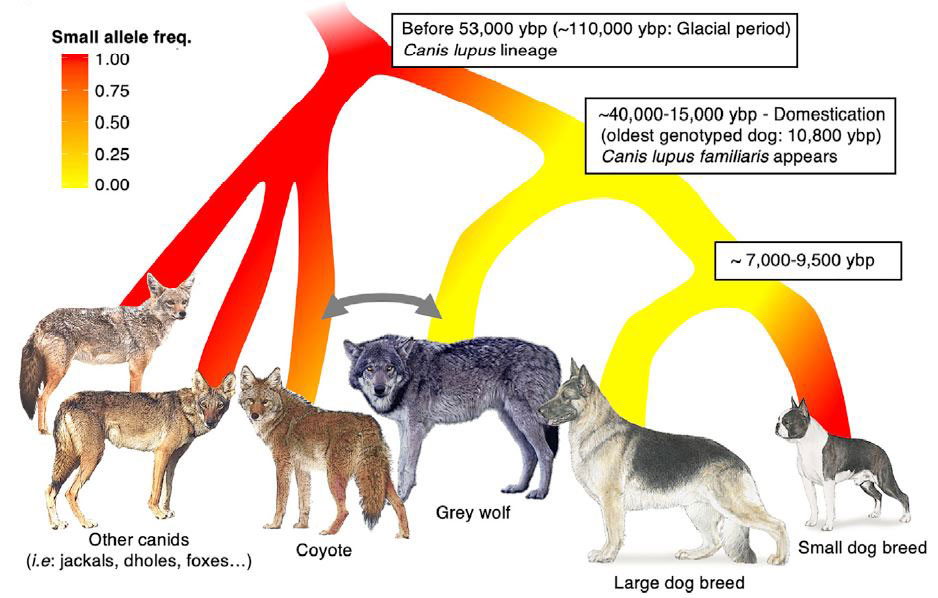

One of the main genetic mutations responsible for small size in certain dog breeds, such as Pomeranians and Chihuahuas, evolved in dog relatives long before humans began breeding these miniature companions. Researchers discovered that the mutation can even be traced back to wolves that lived more than 50,000 years ago.

Researchers discovered the mutation, which is found in the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) gene, by studying data collected as part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Dog Genome Project, a citizen science project in which ownerst collect DNA samples from pet dogs. This "unusual" mutation, found not in the IGF1 gene itself, but rather in DNA that regulates the expression of this gene, had previously evaded researchers for over a decade.

After consulting with scientists in England and Germany, the researchers found that the mutation was present in 54,000-year-old DNA from fossils of Siberian wolves (Canis lupus campestris), as well as in the DNA of every canid species alive today, including jackals, coyotes and African hunting dogs.

Related: The 10 most popular dog breeds

"It's as though nature had kept it tucked in her back pocket for tens of thousands of years until it was needed," senior author Elaine Ostrander, a geneticist at the NIH who specializes in dogs, said in a statement. The discovery helps tie together what we know about dog domestication and body size, she added.

Unusual mutation

Genes are sections of DNA that act as the blueprint for the construction of specific proteins. Each gene is made up of a unique combination of four bases — adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T) — that code for a certain protein. To make a specific protein, cells must unzip the double-stranded DNA in order to read the bases of the strand that contains the corresponding gene. Special machinery within the cell then copies the DNA and creates RNA — a single-stranded molecule similar to DNA with one different sugar (ribose instead of deoxyribose) and the base uracil (U) instead of thymine (T) — which is then used to make the proteins. This process is known as transcription.

The new mutation is located in a section of DNA near the IGF1 gene and regulates its expression, which in turn influences the body size of the dog. There are two versions, or alleles, of this snippet of DNA: One allele has an extra cytosine base (C) that causes smaller body size, and the other allele has an extra thymine base (T) that causes larger body size, Ostrander told Live Science. Each dog inherits two alleles of the gene (one from each parent), meaning it can have either two versions of the small allele (CC), one of each (CT) or two of the large allele (TT), she added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers looked at the DNA of different dog breeds and found a major correlation between alleles and size: Small dogs were CC, medium-size dogs were CT and large dogs were TT.

Getting smaller

After finding the mutation, the NIH researchers wanted to know how far back the alleles could be tracked in canid evolution, which led them to search for the mutation in the DNA of ancient wolves from genomes published in previous studies.

"We were surprised to find the mutation and delighted to find that both variants [C and T] were present over 54,000 years ago," Ostrander told Live Science. The researchers had predicted that the allele for smaller stature was much newer than the one for larger size, but this was not the case, she added.

The IGF1 mutation appears to have played a key role in the evolution of smaller canids such as jackals, coyotes and African hunting dogs, all of which have two copies of the small allele (CC). However, it is extremely unlikely that small dogs would have naturally evolved to become as petite as they are without the intervention of human domestication and breeding, she added.

"The small allele was maintained at a low level [in dogs] for tens of thousands of years until it was selected on during or around the time of domestication," Ostrander said. This breeding was done to create smaller dogs that could better hunt small prey, such as rabbits, she added.

The first slightly smaller dog breeds, which were eventually bred into the extremely miniature versions we see today, emerged between 7,000 and 9,500 years ago, according to the researchers.

Understanding body size

The IGF1 gene is not the only gene that affects a dog's body size. At least 20 known genes code for body size, but this particular gene has an outsize influence: It is responsible for about 15% of body size variance across dog breeds, a large amount for just one gene, Ostrander said.

In comparison, hundreds of genes affect body size in humans, Ostrander said. But it is unsurprising that dogs have fewer body-size-related genes considering that most dog breeds have been around for only a few hundred years, she added.

The researchers will continue to study more body-size genes in dogs to better understand how the genes work together to determine the exact size of every breed, from Chihuahuas to Great Danes. "The next step is to figure out how all the proteins produced by these genes work together to make big dogs, little dogs and everything in between," Ostrander said.

The study was published online Jan. 27 in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus