Just 2 Labs in the World House Smallpox. The One in Russia Had an Explosion.

Here's why there's little risk to human health.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

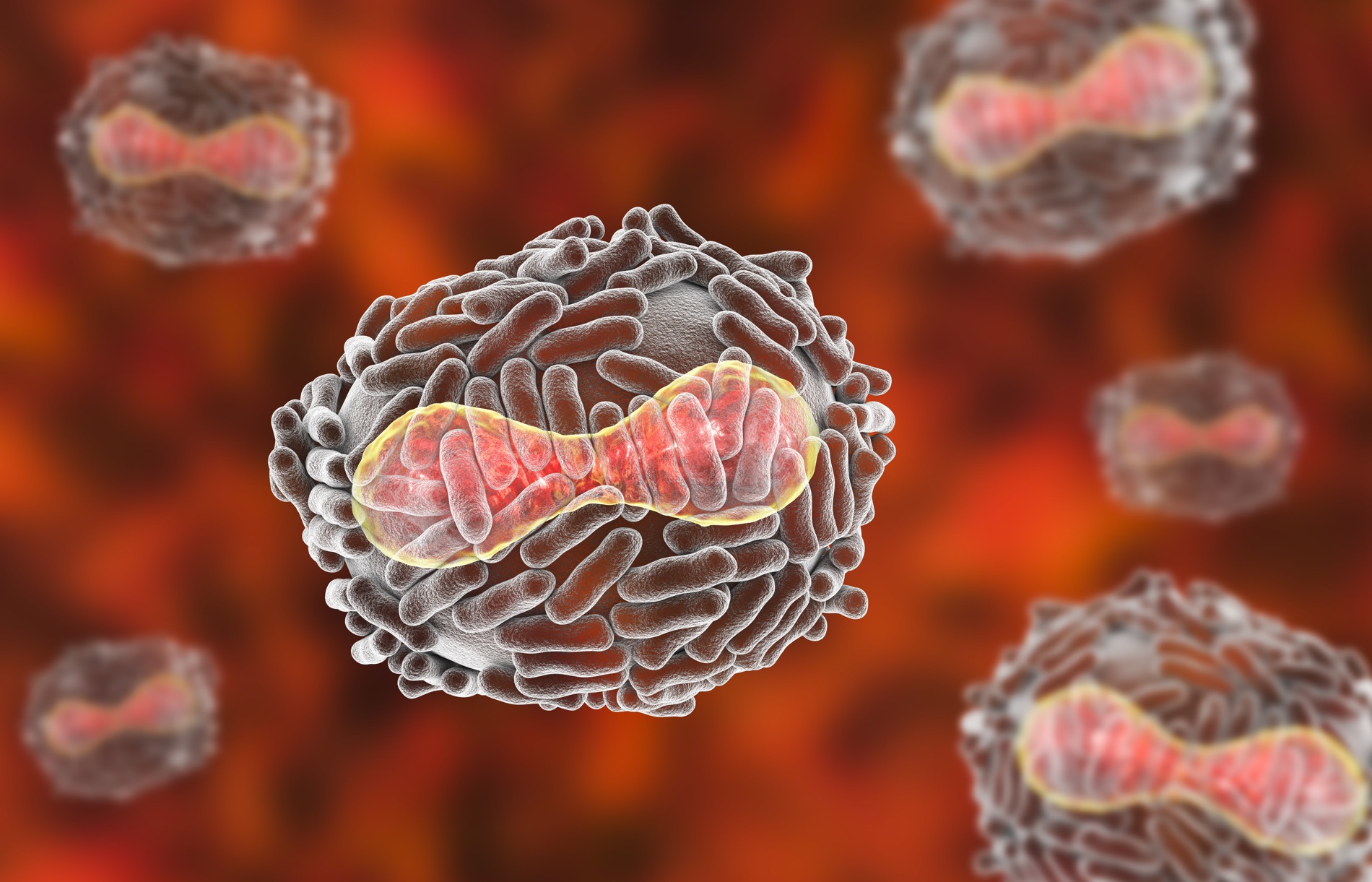

A fire reportedly broke out yesterday (Sept. 16) after an explosion at a secret lab in Russia, one of only two places in the world where the variola virus that causes smallpox is kept. One person was reported injured and transferred to a nearby burn center.

Researchers at the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (also called the Vector Institute), located near Novosibirsk in Siberia, study some scary viruses, including Ebola, anthrax and Marburg. Even so, according to the institute, the fire didn't affect the building where such viruses are kept.

In a translated Russian-language statement from Vector, the lab said a gas cylinder exploded on the fifth floor of a six-story reinforced concrete lab during a repair in the so-called sanitary inspection room. "No work with biological material on the body was carried out," the statement said.

Related: Could Smallpox Ever Come Back?

A Cold War-era bioweapons lab, Vector once housed some 100 buildings and even its own cemetery where a scientist who injected himself with the highly lethal Marburg virus was reportedly buried, the Los Angeles Times reported in 2006.

According to the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), in 2000, a visit to the lab indicated the scientists were no longer "engaged in offensive activities." Today, the scientists there carry out research on the spread of various infectious diseases, vaccine development, virus genome sequencing, among other biomedical studies to "counter global infectious threats," according to the institute's website.

Though outside scientists can't be certain exactly where the explosion and fire occurred, one expert in the field, David Evans, said, "That doesn't sound like it was near where the variola virus is stored or where the research is conducted."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Evans, a professor in the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology at the University of Alberta, is one of the world's experts on poxviruses like smallpox.

Even if the fire had engulfed virus storage facilities, the risk to human health would be very low. "In general, a fire would not be likely to create an infection hazard," Evans told Live Science.

Related: 27 Devastating Infectious Diseases

Another virologist agreed. "Incineration would in all likelihood destroy all of those viruses, including variola virus," Grant McFadden, director of the Center for Immunotherapy, Vaccines, and Virotherapy at Arizona State University, told Live Science in an email.

He added, "Fire is a risk for any biolab, but it is not a high threat of spreading live virus because most viruses are quite heat-labile when they are stored in repositories. That is why they need to be kept in deep freeze incubators for long-term storage."

Indeed, such virus samples are kept frozen and stored inside metal freezers at mind-numbing temperatures of minus 112 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 80 degrees Celsius), Evans said.

"Viruses are fragile things, and a fire in the immediate vicinity would first melt the contents and then consume them," Evans said. "The main concern with any biological collection is that if the power goes out for any length of time, samples warm and melt inside their storage vials and with viruses this can lead to a loss of infectivity."

Those freezers, he emphasized, would surely have mechanical and electrical backups for power.

The other lab authorized by the World Health Organization to hold smallpox — declared eradicated in 1980 — is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia.

- The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth

- 5 Scariest Disease Outbreaks of the Past Century

- 10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus