The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is now running tests on the six forgotten vials of smallpox that were recently discovered in an unsecured laboratory, to see if any live virus remains in them.

The sealed vials were found in a lab at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, and had apparently been languishing there since the 1950s.

But the discovery is not a risk to the public, and even if live smallpox virus were accidentally released in a lab, it would be unlikely to spread disease in the general population, experts say.

"There's no reason for the general public to panic at this discovery," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist and a senior associate at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's Center for Health Security. "There's no risk to the public of smallpox." [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

First vaccine

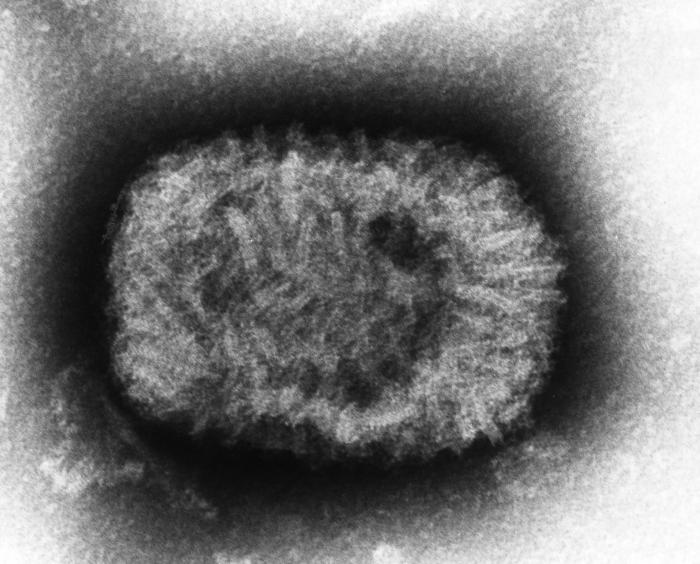

Smallpox is a disease caused by the Variola virus, and is related to several other poxviruses, including cowpox and monkey pox. The virus can spread from one person to another through the air, in respiratory droplets. It causes flulike symptoms, along with characteristic white blisters all over the body. About 30 percent of people who get sick with smallpox go into the serious state of reduced blood flow called shock, and die, Adalja said.

Smallpox has been around since the dawn of recorded history; there are even Egyptian mummies with pockmarked faces, Adalja said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was a big scourge of the human race until it was eradicated from the planet in 1980," Adalja told Live Science.

Long eradication process

The first vaccine against smallpox was developed in the 1700s, when biologist Edward Jenner noticed that women who milked cows were immune to smallpox after they had been infected with the much milder disease of cowpox, or vaccinia. So in 1796, Jenner inoculated people using pus from those infected with the cowpox virus, creating the world's first vaccine.

For hundreds of years, the live vaccinia vaccine was grown in cow skins, then in tissue cultures in the lab, but such vaccines caused complications. Scientists have since developed a third-generation vaccine that uses live-but-weakened virus, and doesn't have those side effects, said Grant McFadden, a virologist at the University of Florida who studies poxviruses.

Thanks to a worldwide effort to wipe out the disease, smallpox was declared officially eradicated in 1980, after the last natural occurrence of the disease happened in Somalia in 1977, and the last death from the disease occurred due to a laboratory accident in England in 1978, according to the World Health Organization.

Disease resurgence

The vials of smallpox discovered in the NIH research lab were completely sealed, so it's extremely unlikely anyone was exposed to the virus, McFadden said. In addition, now that the vials are in the hands of the CDC, they're in one of the two laboratories in the world with the necessary safety protocols and approval to handle the virus. (The other known place that houses live smallpox is a laboratory in Koltsovo, Russia.)

Even if someone were infected in a lab accident, there's an almost nonexistent risk of the disease spreading in the general population, Adalja said.

People aren't infectious until they start showing the characteristic rash. So health workers have time to implement a "ring strategy" of containment, meaning any exposed person would be quarantined and vaccinated, and all the people they come into contact with would be immunized against the disease. The same ring strategy successfully eliminated the disease in the 1970s, Adalja said.

Bioweapon

The risks from a lab accident are extremely low, but there's still a murky, impossible-to-quantify risk that rogue nations or terrorists could try to deploy smallpox as a weapon, McFadden said. The Russians did try to make biological weapons from viruses, such as Ebola, during the Cold War.

"Nobody knows if there are weaponized stockpiles of Variola virus out there or not," McFadden told Live Science.

If someone were to deploy a weaponized form of the virus, few people today would have any immunity, meaning it could theoretically be more infectious than it was in the past, Adalja said.

But on the other hand, because of the bioterrorism threat, the United States has protocols in place to quickly contain a smallpox outbreak, and has stockpiles of the smallpox vaccine, he said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus