Surprising loss of sea ice after record-breaking Arctic storm is a mystery to scientists

Although models accurately predicted the evolution of the Arctic storm, scientists were surprised to see just how much sea ice thickness decreased in the storm's aftermath.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Early in 2022, the Arctic experienced its strongest cyclone on record, with wind speeds reaching 62 mph (100 km/h). Although storms aren't rare in the Arctic, this one led to an extensive loss of sea ice that surprised Arctic researchers.

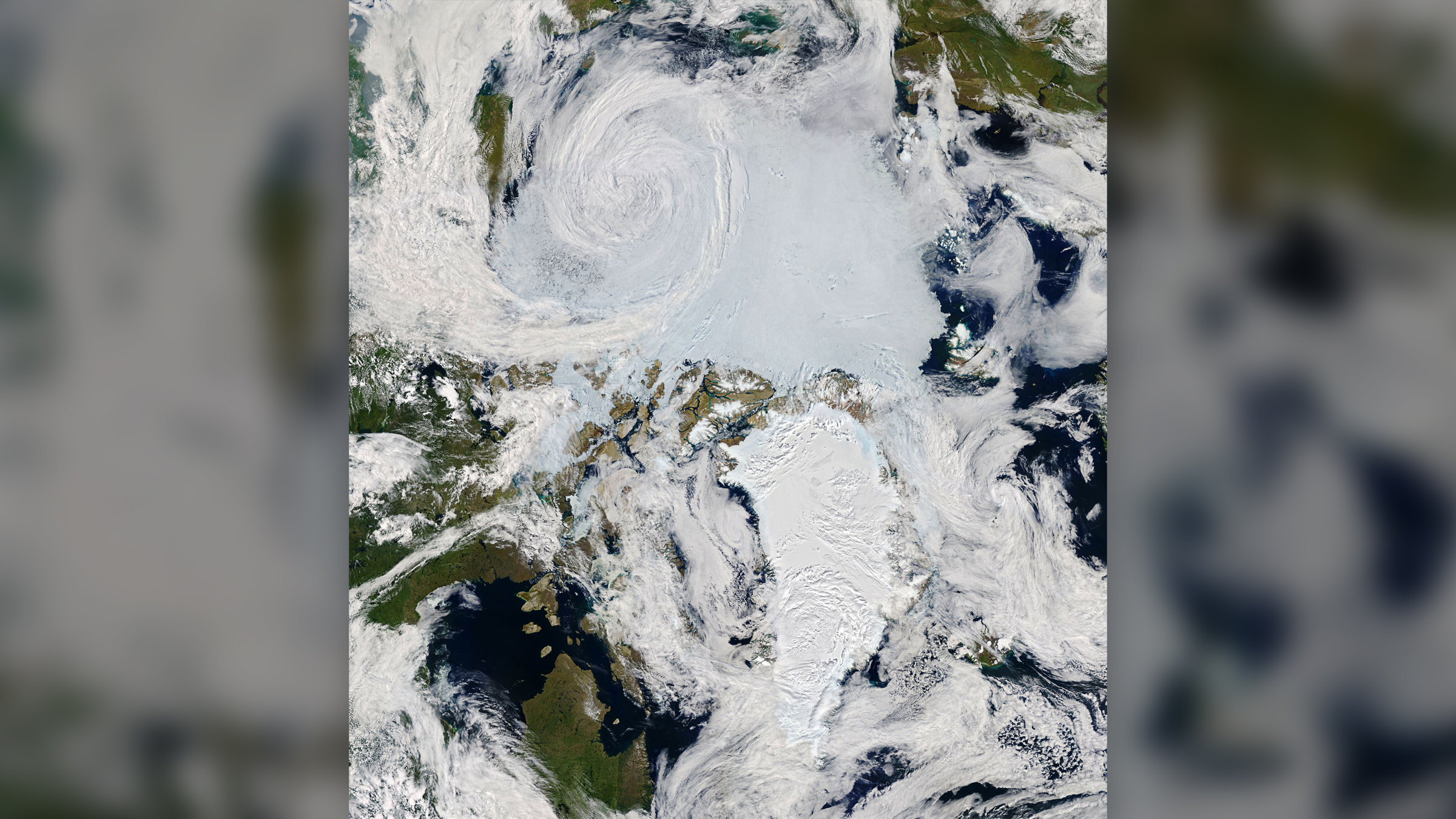

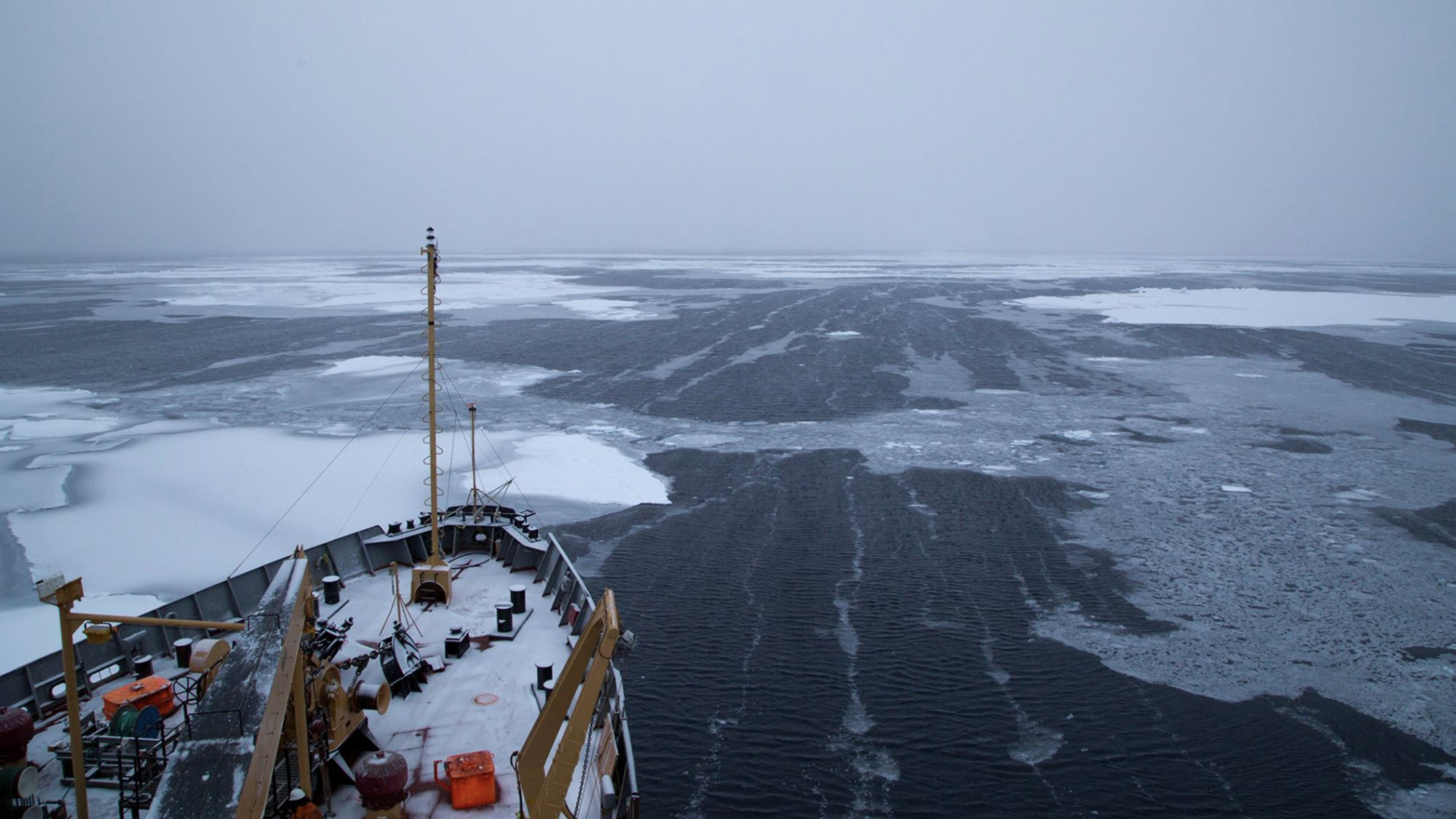

In the Arctic, sea ice — frozen seawater that floats over the ocean in the polar regions — reaches its largest coverage in March and what is thought to be its thickest maximum in April, researchers told Live Science. But as sea ice was building up this year, it hit a major setback. Between Jan. 20 and Jan. 28, the storm developed over Greenland and traveled northeast into the Barents Sea, where massive waves reached 26 feet (8 meters) high. Like a wild bronco, those waves bucked sea ice at the edge of an icy pack 6 feet (2 m) up and down, while even larger waves swept 60 miles (100 km) toward the center of the pack. Although weather models accurately predicted the evolution of the storm, sea ice models did not predict just how much the storm would affect ice thickness.

Six days after the storm dissipated, the sea ice in the affected waters north of Norway and Russia had thinned 1.5 feet (0.5 m) — twice as much as what sea ice models had predicted. Researchers analyzed the storm in a study published Oct. 26 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

Related: The Arctic's most stable sea ice is vanishing alarmingly fast

"The loss of sea ice in six days was the biggest change we could find in the historical observations since 1979, and the area of ice lost was 30% greater than the previous record," lead author Ed Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, said in a statement. "The ice models did predict some loss, but only about half of what we saw in the real world."

The study found that atmospheric heat from the storm affected the area minimally, so something else must have been going on.

The paper authors offered a few ideas for why the sea ice thinned so much, so fast. It could have been that their models had wrongly estimated the sea ice thickness before the storm. Or perhaps the storm's violent waves broke up the sea ice more than anticipated. It could also be that the waves churned up deeper, warmer water, which then rose to melt the sea ice pack from the bottom.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sea ice thickness is notoriously hard to study and model. Interactions between the ice, ocean and atmosphere affect sea ice thickness in ways that scientists don't fully understand. And some of these interactions happen on too small of a scale to model. For instance, scientists know that pools of melted water that appear on the top of sea ice in the Arctic summer do influence sea ice thickness, but that effect is hard to model. Melt pools also can throw off satellites, which may measure those pools as "ocean" rather than water on top of sea ice.

And as the climate warms, it's more important than ever to understand Arctic storms and their effect on sea ice. In a paper published in the journal Nature Communications in November, a team of NASA scientists found that sea ice loss and warmer temperatures will lead to stronger Arctic storms by the end of the century. Those more intense storms could bring rainfall that could melt sea ice, cause warmer temperatures and churn up warmer water from deep below.

"Going into the future, this is something to keep in mind, that these extreme events might produce these episodes of huge sea ice loss," Blanchard-Wrigglesworth said.

JoAnna Wendel is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon. She mainly covers Earth and planetary science but also loves the ocean, invertebrates, lichen and moss. JoAnna's work has appeared in Eos, Smithsonian Magazine, Knowable Magazine, Popular Science and more. JoAnna is also a science cartoonist and has published comics with Gizmodo, NASA, Science News for Students and more. She graduated from the University of Oregon with a degree in general sciences because she couldn't decide on her favorite area of science. In her spare time, JoAnna likes to hike, read, paint, do crossword puzzles and hang out with her cat, Pancake.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus