Move over polar bears, there's another top predator along the Arctic coast

A new study has revealed that certain sea stars rival polar bears as the most prolific predators in coastal Arctic ecosystems.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In coastal ecosystems around the Arctic peninsula, polar bears have long been considered the top predators. But a new study suggests that sea stars could be surprising contenders to rival the famous white bears at the summit of the local food web.

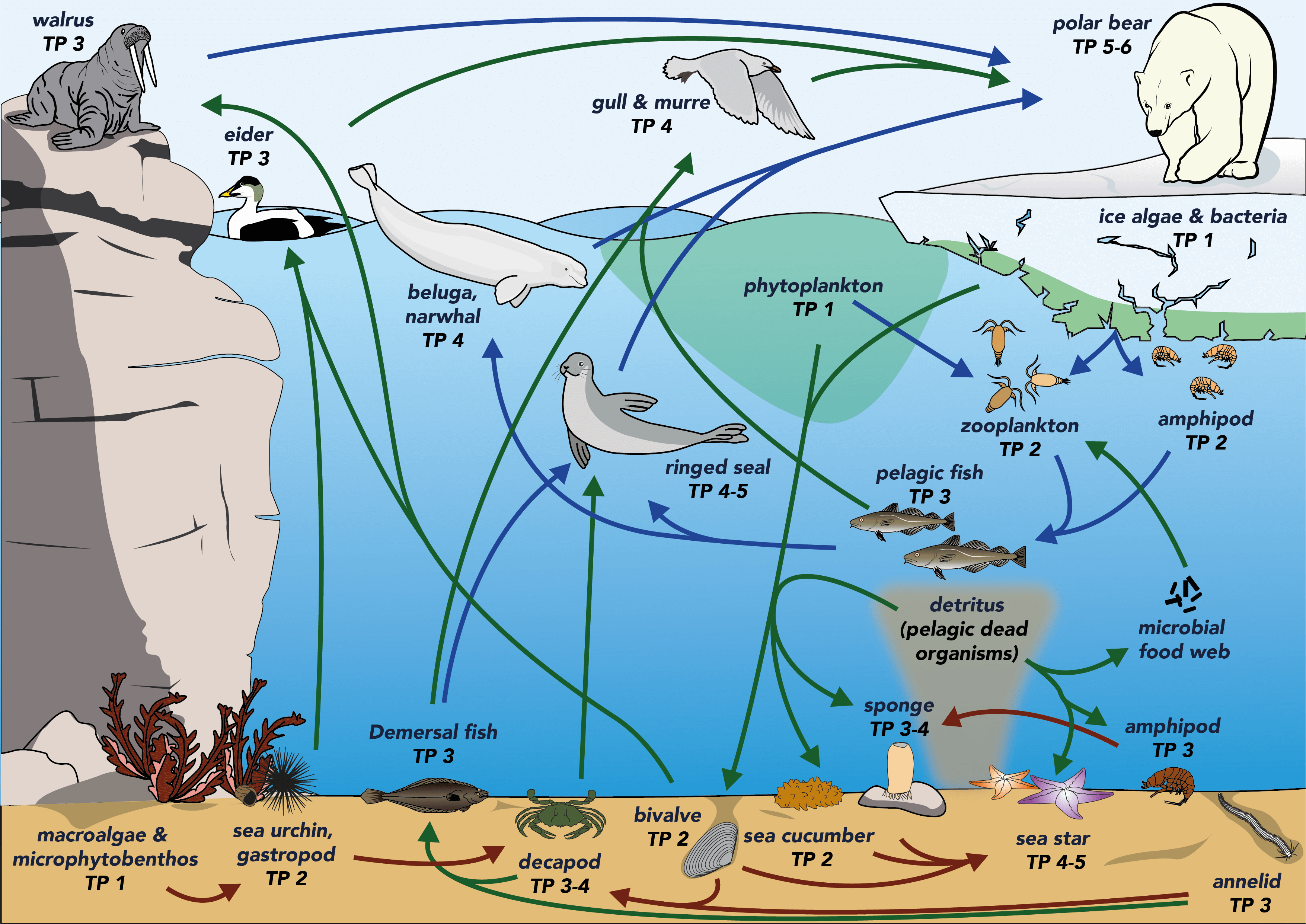

A food web is a sprawling map of ecological connections that combines all the different food chains within an ecosystem. Individual food chains contain primary producers, which derive energy from the sun or by recycling dead organic material; primary consumers that graze upon the primary consumers; and then secondary or tertiary consumers that prey upon all the consumers beneath them. But the organisms in one food chain can also have a place in another, or multiple others, so the best way to see how an ecosystem functions is to link these chains together.

In marine food webs, researchers often focus on pelagic, or open water, food chains that contain tiny, surface-dwelling plankton all the way up to large predators such as polar bears (Ursus maritimus), which often sit at the top of multiple food chains. But the seafloor, or benthic, realm is often overlooked in marine food webs because scientists believed it has no real top predators of its own.

Article continues belowBut in a new study, published Dec. 27, 2022, in the journal Ecology, researchers took a more in-depth look at a coastal marine ecosystem in the Canadian Arctic and found that the benthic component of the region’s food web had been majorly underappreciated. The research team created a detailed map of the various food chains surrounding Southampton Island, in the mouth of Hudson Bay in Canada's Nunavut territory, and found that the benthic part of the web had just as many connections as its pelagic counterpart, as well as its own equivalent of the polar bear — predatory sea stars.

Related: Swarm of rainbow-colored starfish devour sea lion corpse on seafloor

"It’s a shift in our view of how the coastal Arctic marine food web works," study lead author Rémi Amiraux, a marine ecologist at Laval University in Canada who was with the University of Manitoba when the study was conducted, said in a statement. "We proved that the wildlife inhabiting the seawater and those inhabiting the sediment form two distinct but interconnected subwebs."

The researchers analyzed data on 1,580 individual animals living in the Southampton Island coastal ecosystem to create the new food web. They found that the benthic and pelagic components each had a similar number of steps, or trophic levels, in their respective food chains.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sea stars were a key part of the benthic food web, occupying various trophic levels, but one family, Pterasteridae, was consistently at the top of most individual food chains. The researchers discovered that these sea stars feed on a range of secondary consumers including bivalves, a group of mollusks whose bodies are protected by a hinged shell, sea cucumbers and sponges. This means Pterastidae sea stars were hunting on an equivalent scale to polar bears, which preyed upon walruses, gulls, beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and ringed seals (Pusa hispida). The key difference between the polar bears and sea stars was the size of their prey.

In addition to being among the most successful predators in the entire ecosystem, the Pterasteridae sea stars and polar bears also shared the ability and willingness to scavenge, which researchers believe has enabled both groups to thrive in the Arctic.

The sea stars opportunistically fed on dead pelagic organisms that sank to the seafloor, meaning they had to hunt less often. Similarly, polar bears can scavenge on whales that wash up dead, which can sustain them for weeks or even months, researchers wrote in the study.

The team believes that the new findings highlight the importance of seafloor food chains in many other marine food webs. Pterasteridae sea stars are found in almost all marine ecosystems, and if they are as successful elsewhere as they are in the Arctic, they could turn out to be one of the ocean's most successful predators, researchers wrote.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus