City-size seamount triple the height of world's tallest building discovered via gravitational anomalies

Researchers found and mapped four seamounts in the deep sea off the coast of Peru and Chile. The tallest of these new peaks rises around 1.5 miles above the seafloor.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

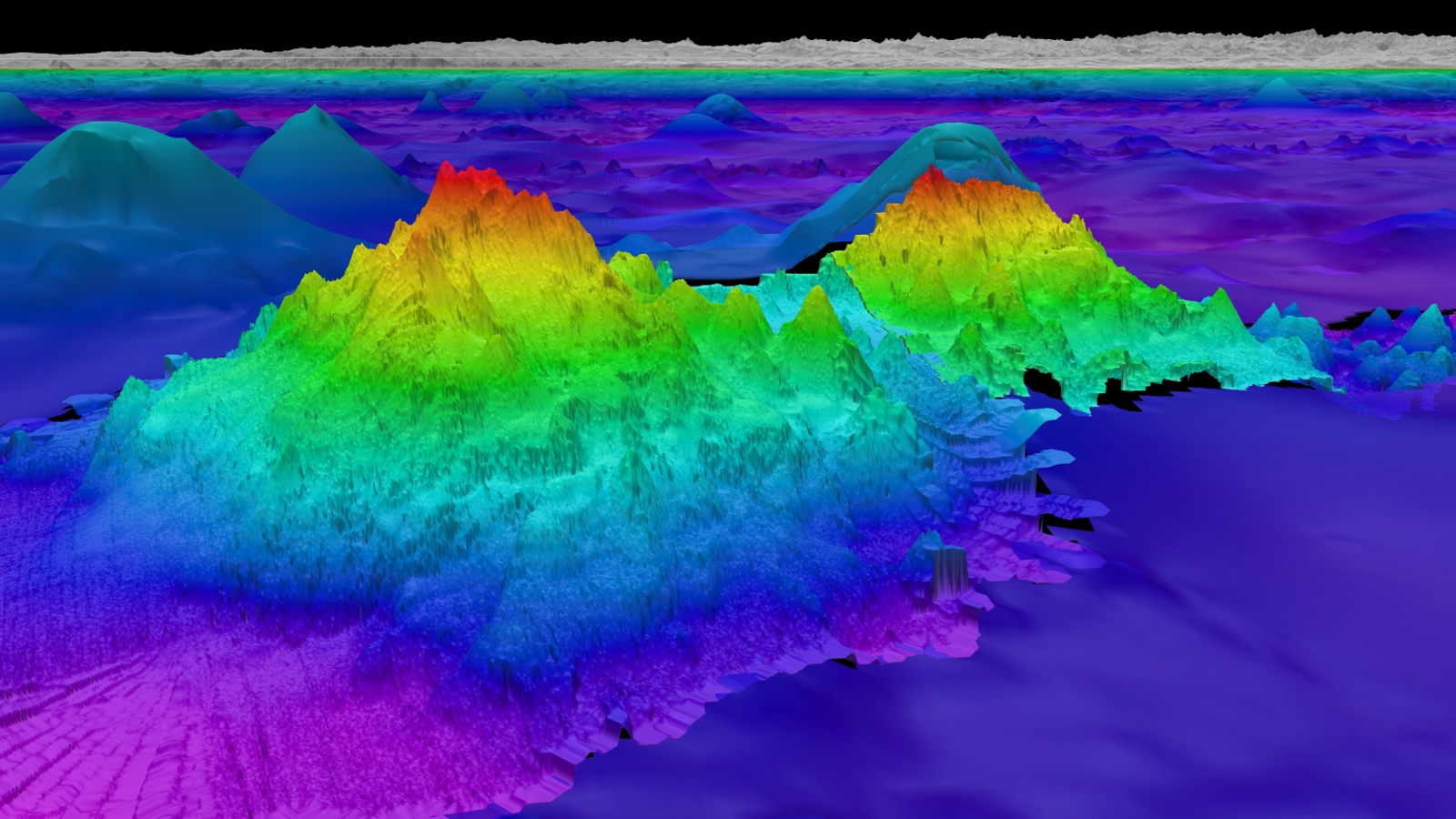

Researchers have discovered four gigantic seamounts towering above the seafloor surrounding South America after detecting "gravitational anomalies" given off by the massive underwater mountains. The tallest rises more than 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) from the seafloor, making it three times taller than the world's tallest building.

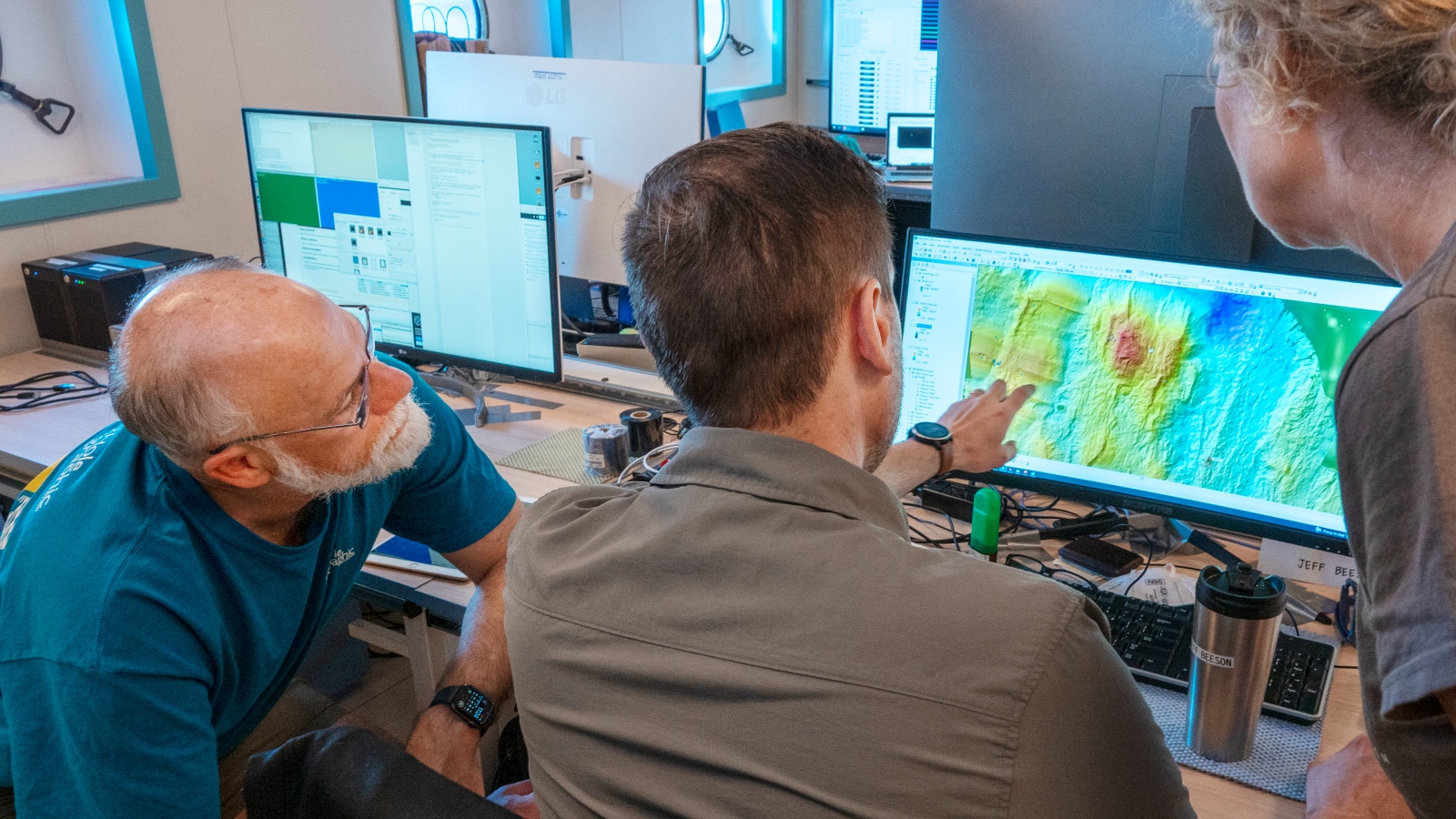

Scientists aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute's Falkor (too) research vessel recently discovered and mapped the quartet of seamounts in the deep sea between 286 and 373 miles (460 and 600 km) off the coast of Peru and Chile during an expedition through the East Pacific from Costa Rica to Chile.

The three Peruvian peaks measured 5,220 feet (1,591 meters), 5,459 feet (1,644 m) and 6,145 feet (1,873 m) tall respectively. But the largest seamount, found off Chile, rises 8,796 feet (2,681 m) above the ocean's bottom, bringing it to within a mile of the surface. For comparison, the world's tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, is 2,716 feet (828 m) tall, while the Empire State Building stands at 1,250 feet (380 m).

The tallest peak also has a surface area of around 175 square miles (450 square km), which is around the same size as New Orleans.

These giant underwater peaks, which are all extinct volcanoes, are so massive that they create subtle changes in the height of the ocean's surface, and these so-called gravitational anomalies can be detected by satellites. In this case, the ocean's surface bulges right above the peaks.

"Examining gravity anomalies is a fancy way of saying we looked for bumps on a map, and when we did, we located these very large seamounts," John Fulmer, the expedition's lead technician, said in a statement emailed to Live Science.

Related: 10 mind-boggling deep sea discoveries in 2023

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Last year, the same research team found another massive seamount that was around twice the size of the Burj Khalifa. But there are several bigger underwater mountains.

The world's largest seamount is technically Hawaii's dormant volcano Mauna Kea, according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. It stands at around 13,796 feet (4,205 m) above sea level but extends to the seafloor, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Its true height is around 33,500 feet (10,211 m).

Scientists suspect that up to 100,000 seamounts are littered across the world's oceans, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. However, only a small fraction of these have been mapped. More than half of these predicted peaks are thought to be in the Pacific Ocean.

The latest expedition is part of a new project, named Seabed 2030, which aims to map the entirety of the world's seafloor by the end of the current decade and should reveal the rest of these hidden peaks in all their glory.

Seamounts are often referred to as "biological hotspots" by marine researchers. The structures provide a hard substrate for immobile creatures such as corals and sponges to settle and cause "upwelling" when currents drag nutrients from the deep sea closer to the surface. This attracts larger creatures — including crustaceans, fish, cephalopods and sharks — which makes seamounts extremely important marine habitats.

"Locating seamounts almost always leads us to understudied biodiversity hotspots," Jyotika Virmani, executive director of the Schmidt Ocean Institute, said in the statement. "Every time we find these bustling seafloor communities, we make incredible new discoveries and advance our knowledge of life on Earth."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus