Nuclear fusion reactor in UK sets new world record for energy output

The JET nuclear fusion reactor in the UK has set a new world record for total energy output. However, the reactor's record-smashing test will be its last.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A nuclear reactor in the U.K. has just broken a new fusion record.

In a news conference today (Feb. 8), representatives from the Joint European Torus (JET) facility declared that the reactor's final tests yielded 69.26 megajoules of heat from just 0.21 milligrams of fuel — the equivalent of burning 4.4 pounds (2 kilograms) of coal. This is more total energy — though not more net positive energy — than any other fusion reaction has produced thus far.

Tests such as this could help unlock fusion as a viable source of clean, near-limitless energy, the researchers said.

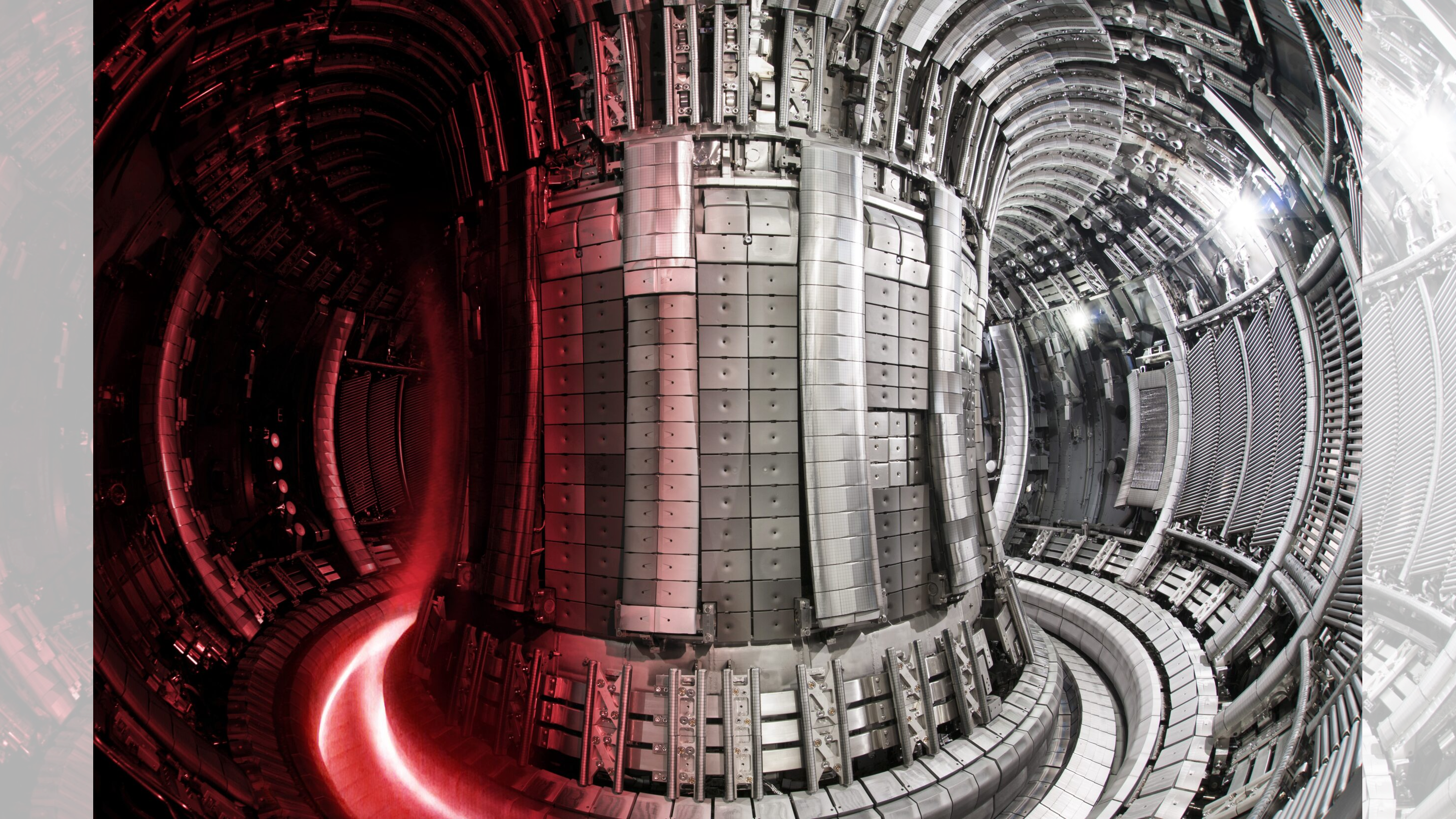

JET first fired up in 1983 in Oxfordshire, England. Its doughnut-like shape, known as a tokamak, allows scientists to whip modified hydrogen atoms into hot plasma by accelerating them to breathtaking speeds using a magnetic field. This setup creates the necessary conditions for nuclear fusion — the combination of two light atomic nuclei into one heavier one, releasing enormous amounts of energy in the process.

Over the course of its 40 years of operation, JET has produced numerous fusion milestones, including becoming the first reactor to use a 50/50 mixture of deuterium (hydrogen with an extra neutron) and tritium (hydrogen with two extra neutrons) atoms — now considered a standard fusion fuel.

"We can reliably create fusion plasmas using the same fuel mixture to be used by commercial fusion energy powerplants, showcasing the advanced expertise developed over time," Fernanda Rimini, JET's scientific operations leader, said in a statement.

Related: Nuclear fusion reactor 'breakthrough' is significant, but light-years away from being useful

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, this record will be JET's last. The project was decommissioned in December 2023, shortly after the record-breaking test took place. Researchers have now begun the arduous process of taking the reactor apart, a task that is expected to last until 2040. But over that time, they hope to learn even more about what made JET tick, including how renegade plasma blasts affected the tokamak's internal structure. It will also help scientists develop safer strategies to dispose of radioactive waste, the team said.

JET's legacy will live on in the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a massive tokamak in southern France scheduled to start up in 2025. The $22 billion dollar project will use a very similar fusion strategy, but at a much larger scale.

"Throughout its lifecycle, JET has been remarkably helpful as a precursor to ITER," Pietro Barabaschi, ITER's director-general, said in the statement. "The results obtained here will directly and positively impact ITER, validating the way forward and enabling us to progress faster toward our performance goals once operation begins."

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus