Solar Probe Finds Active, Mysterious Corona, Surprising Scientists

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has passed through the outer atmosphere of the sun, and now we get to see what it found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The first mission to the sun has reached the star's corona, or outer atmosphere, where temperatures soar to a few million degrees. There, the probe found "rogue" ripples disrupting parts of that atmosphere, a discovery that could help solve a long-standing mystery about this hot ball of gas.

The probe's discoveries could also help astronomers predict when our home star will lash our planet with fiery jets of plasma, triggering powerful magnetic storms and causing mass blackouts.

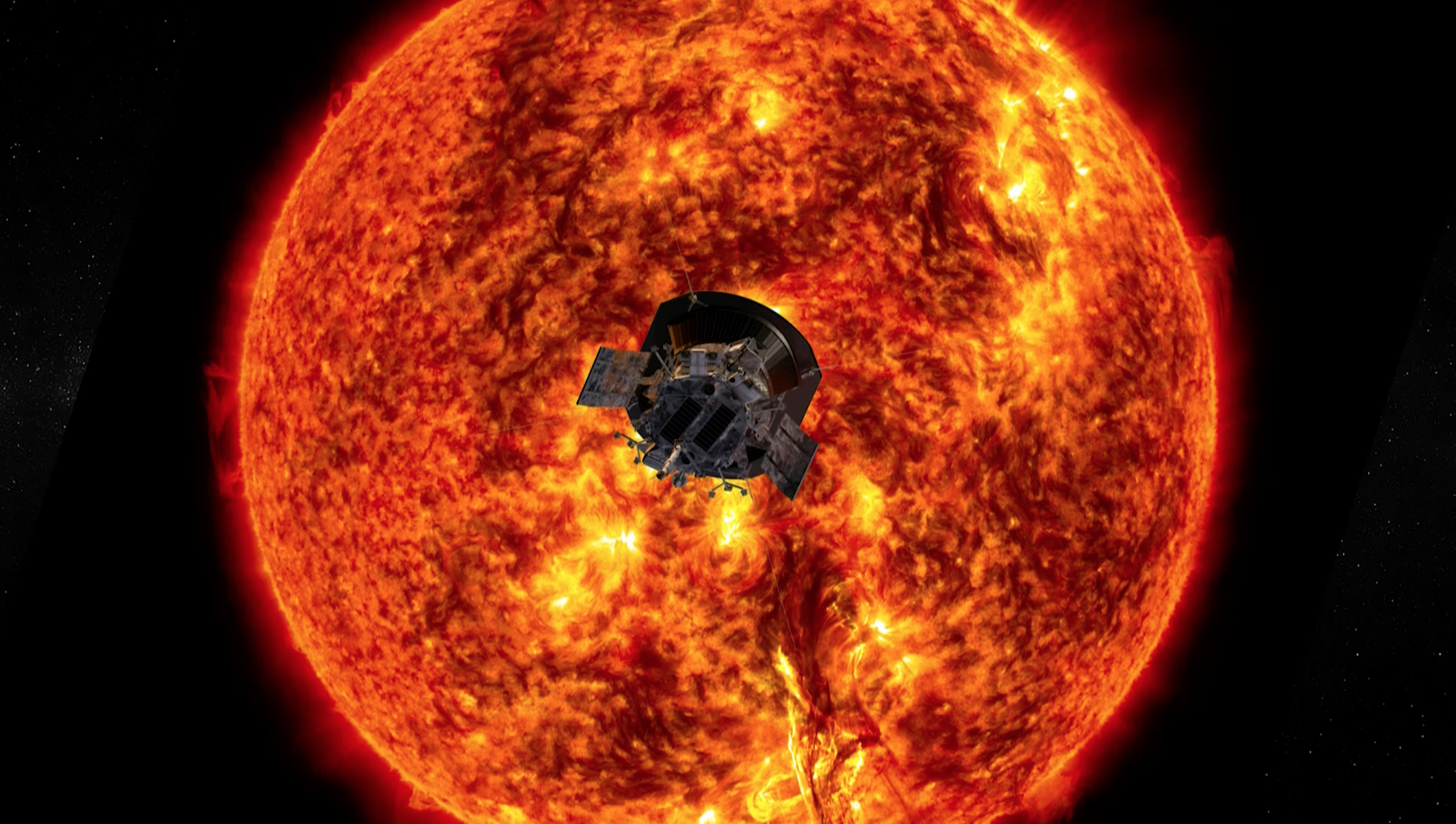

NASA's Parker Solar Probe (which is about the size of a large car) launched Aug. 12, 2018. It has since completed two full orbits of the sun, zipping within 15 million miles (24 million kilometers) of the solar surface and passing through the corona, the source of the solar wind that can strike Earth. The spacecraft will shift much closer to the sun during future orbits, but already, its findings have changed how astronomers see our home star.

Related: Incredible Photos of Solar Flares

"Even with just these first orbits, we've been shocked by how different the corona is when observed up close," Justin Kasper, a researcher at the University of Michigan who leads one part of the Parker Solar Probe science mission, said in a statement. "These observations will fundamentally change our understanding of the sun and the solar wind and our ability to forecast space weather events."

Published as a series of four papers in the journal Nature on Wednesday (Dec. 4), those observations painted a picture of a corona that is both more active and more mysterious than it appeared based on observations from Earth.

For example, the probe found that researchers were wrong about how the sun aims its blasts of solar wind into space. Scientists knew that the sun's magnetic field tugged on winds as they made their way out of the corona, but the probe found that effect to be 10 to 20 times more powerful than scientists had thought. That means researchers will need to completely rewrite calculations used to predict space weather.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This has huge implications. Space weather forecasting will need to account for these flows if we are going to be able to predict whether a coronal mass ejection will strike Earth or astronauts heading to the moon or Mars," Kasper said.

The probe also turned up new clues that could help resolve an old mystery: Why does the corona get hotter the farther you are from the sun's surface?

Some researchers had suspected that magnetic "Alfvén waves," oscillations long ago discovered in the solar wind, might play a role. The Parker Solar Probe detected those waves behaving in a strange and unexpected way in the neighborhood closer to the sun.

"When you get closer to the sun, you start seeing these 'rogue' Alfvén waves that have four times the energy than the regular waves around them," Kasper said. "They feature 300,000-mph [480,000 km/h] velocity spikes that are so strong, they actually flip the direction of the magnetic field."

- The 18 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

- The Large Numbers That Define the Universe

- Twisted Physics: 7 Mind-Blowing Findings

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus