Best-preserved dinosaur stomach ever found reveals 'sleeping dragon's' last meal

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The last meal of the 3,000-lb. (1,360 kilograms) "sleeping dragon" dinosaur is so beautifully preserved, scientists now know exactly what the armored beast ate before it died about 112 million years ago, a new study finds.

Extraordinary circumstances left the remains of this giant dinosaur in pristine, lifelike condition. After it died, the body was swept out to sea, bloated with gas and remained afloat until it sank in an oxygen-poor area perfect for preservation; and its tough, boney armor likely deterred marine predators, researchers previously told Live Science.

Turns out, the nodosaur's stomach contents were just as remarkably preserved as the rest of its body. An analysis of its fossilized soccer-ball-size stomach contents reveals that this dinosaur, known as Borealopelta markmitchelli, was an extremely picky eater. It ate ferns, but only certain types, and only select parts of those plants.

"These remains are amazingly well preserved. You can see the cellular detail of the plants," study co-lead researcher Caleb Brown, a curator at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta, Canada, told Live Science. "When we first looked at the slides under the microscope, it was one of those moments where it's like 'whoa.'"

Related: Photos: This plant-eating dinosaur had spikes, armor and camouflage

Image Gallery

Miners found the remains of the 18-foot-long (5.5 meters) nodosaur — a cousin of the Ankylosaurus — in 2011 at the Suncor Millennium Mine in Alberta. With only its tail and hind legs missing, the herbivorous beast is the most well-preserved armored dinosaur on record.

While it's more common to find the stomach remains of carnivorous dinosaurs (after all, the prey's bones are often fossilized within the beast that ate it), it's rare to find the fossilized remains of a herbivorous dinosaur's last meal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That's "because often the preservational requirements to preserve bone are different than preserving plants," Brown said. "So you'd have to have both of those occurring at the same time," to preserve both the herbivore's bones and its meals. Furthermore, it can be difficult to determine if fossilized plants were part of the dinosaur's diet or simply at the spot where it died, he added.

There are only about 10 reported cases of herbivorous dinosaurs' last meals, and "I'd say in two-thirds of those, there's really no good evidence that they are stomach content," Brown said. "They're just leaves that got buried at the same time as the animal."

As a result, it's hard to know which species of plants, and what parts of those plants, that herbivorous dinosaurs ate. Enter B. markmitchelli; this dinosaur not only had good preservation but also was fossilized out at sea, away from land plants. In other words, it would be extremely unlikely that land ferns just happened to be in the marine environment where the dinosaur's body came to rest.

Fern nutritional reasons

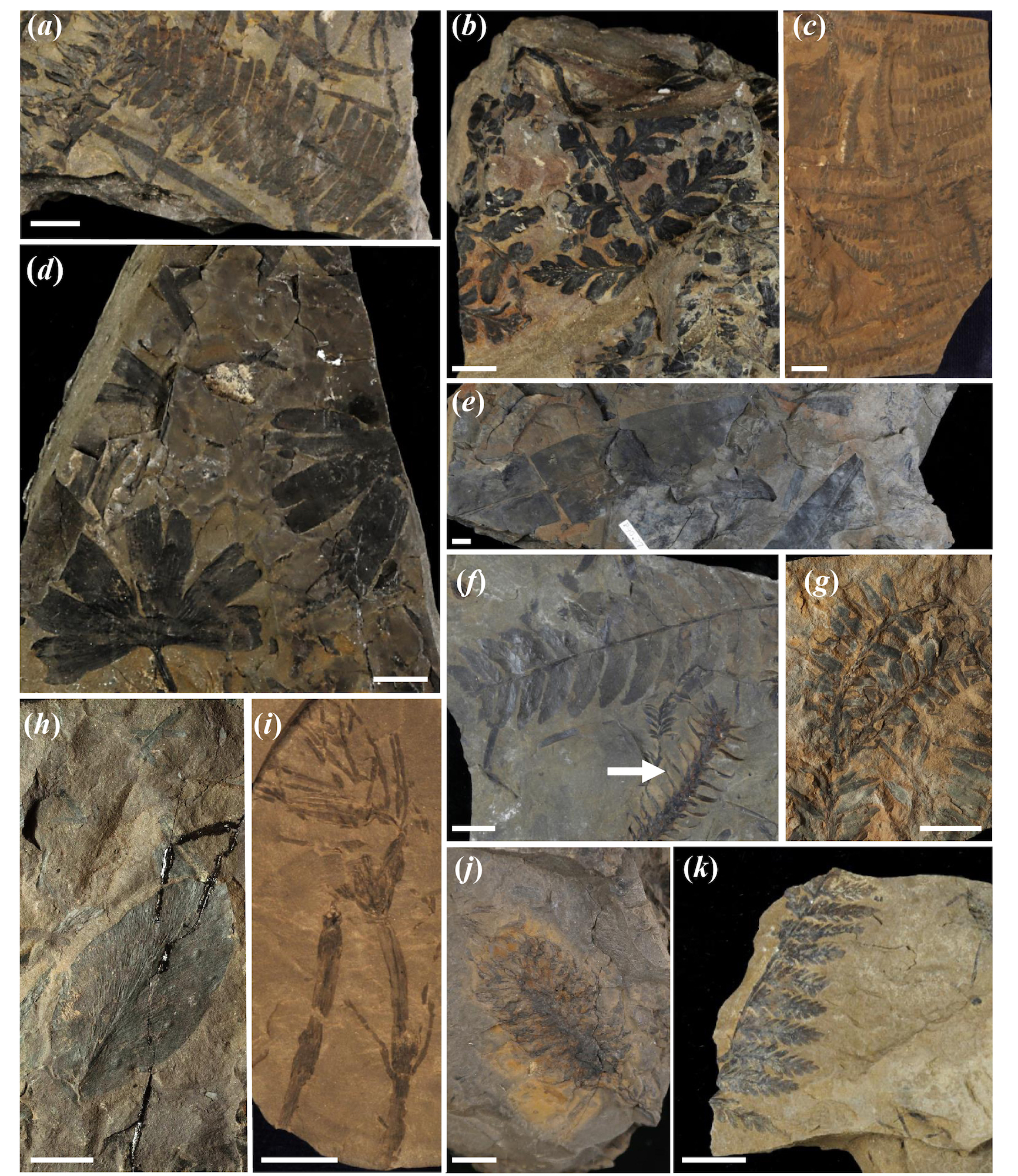

To study the nodosaur's last meal, researchers made slides out of a few ping pong-ball-size chunks of the fossilized stomach content. They found that leaves accounted for nearly 88% of the plant material, and less than 7% comprised stems and wood. Charcoal accounted for about 6%.

The majority of those leaves were from leptosporangiate ferns, with just a tiny amount from cycads (an ancient group of seed plants) and even less from conifers (modern conifers include plants with pine cones).

"We recognized at least five different kinds of ferns from the microscopic sporangia [the place where spores form] in the stomach contents, but there were many more that we identified from spores dispersed in the stomach," study co-lead researcher David Greenwood, a professor of biology at Brandon University in Manitoba, Canada, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: See the armored dinosaur named for Zuul from 'Ghostbusters'

In particular, the researchers found sporangia with a specialized ring of thickened cells that acts as a spring to fling spores into the air, Greenwood said. This ring is found only in leptosporangiate ferns common today in gardens and woods. B. markmitchelli didn't seem to favor eusporangiate ferns, which lack this ring, even though the ferns were common in the dinosaur's stomping grounds, according to fossilized evidence.

Nor did the dinosaur eat (at least according to fossil evidence) horsetails, cedar plants or tropical plants also in the area. To put it mildly, it looks like B. markmitchelli had very specific taste in plants. Just like a modern deer, "it selected which plant parts and which plants it ate," Greenwood said.

Even so, this gut material "is a snapshot of what one dinosaur ate on one particular day," said Karen Chin, an associate professor and a curator of paleontology at the University of Colorado Boulder, who was not involved in the research. "We have to avoid assuming that the gut contents are representative of the dinosaur's everyday diet."

What's more, this dinosaur's diet could have changed over its life span and as the seasons changed, Chin said.

Self medication?

The charcoal found in the nodosaur's belly suggests the dinosaur consumed its last meal in a recently burned area. "Many animals today self-medicate by eating charcoal," Greenwood said. "We don't know if Borealopelta was doing that, but the charcoal in its stomach says it was eating its last meal in an area that had burnt in a wildfire in the last 6-18 months."

Perhaps, like many modern day grazing mammals, it preferred to eat in recently burned areas, as it was easier to move around and find newly growing, nutritious plants to eat, Greenwood noted.

Stones, also known as gastroliths, were also found in the gut and ranged from pea- to grape-size, Brown said. They were used to help the creature break down the fibrous plants it had eaten. This technique is seen in birds today. (Birds evolved from carnivorous dinosaurs known as theropods.)

Related: Photos: Spiky-headed dinosaur found in Utah, but it has Asian roots

The stomach contents also revealed the season of death. Based on the woody stems' growth rings and the mature sporangia, it appears that this dinosaur died during the late spring to mid-summer, the researchers found.

The study was published online today (June 3) in the journal Royal Society Open Science. The nodosaur is on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology.

- Photos: This dinosaur's feathers shimmered with iridescence

- Photos: Incredible near-complete Stegosaurus skeleton

- Image gallery: Tiny-armed dinosaurs

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus