Mysterious event nearly wiped out sharks 19 million years ago

It's unknown whether the ancient sharks died off in a single day, weeks, years or even thousands of years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Some 19 million years ago, a mystery event nearly drove the world's entire population of sharks to extinction, according to a new study.

About 90% of sharks disappeared from the oceans in less than 100,000 years, but it's unknown why and whether they died off in a single day, weeks, years or even thousands of years. This extinction event significantly altered the ancient marine environment, and sharks never recovered from the die-off, according to the study, which was published Thursday (June 3) in the journal Science.

"Sharks have been around for 400 million years; they've weathered a lot of mass extinctions," some of which wiped out almost all life, said co-author Elizabeth Sibert, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University's Institute for Biospheric Studies (who was a junior fellow at Harvard University at the start of the research). Yet during the early Miocene epoch, something "clearly happened to almost wipe this group off of the face of this Earth."

Related: In photos: Seeing sharks up close

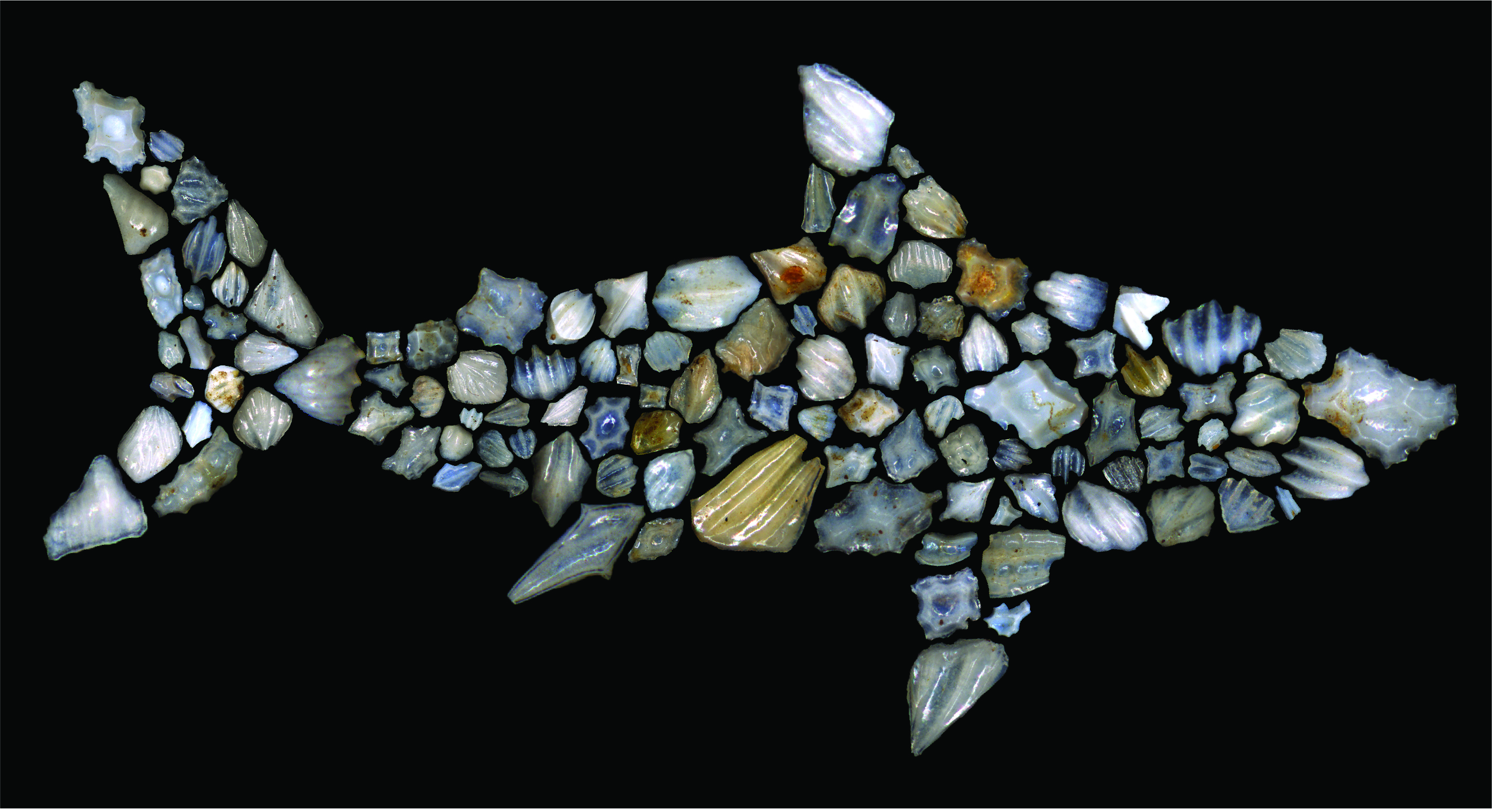

This story was hidden inside a largely ignored group of ichthyoliths, which are microscopic fossils of shark scales (called denticles) and fish teeth buried deep inside sediments on the ocean floor.

Ichthyoliths are found in most types of sediments, but they are tiny and relatively rare compared with some other microfossils that are better studied, Sibert said. In fact, though some scientists studied ichthyoliths in the 1970s and '80s, few researchers had examined them in the decades since, until Sibert investigated them for her doctorate, which she completed in 2016.

"A lot of what I've done in my early career as a scientist was figuring out how to work with these fossils, what kinds of questions we can ask about them," Sibert told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ichthyoliths are found inside deep sediment cores, or sediments that have been stacked on the ocean floor over millions of years. The deeper the sediment, the older it is, with some sediment cores dating back 300 million years, Sibert said. These sediment cores allow researchers to create a time series: A certain number of inches down the core equals a certain number of years in history.

Sibert and another group of researchers previously discovered that the number of shark ichthyoliths in such cores greatly declined 19 million years ago, but it wasn't clear if this drop represented an extinction event.

In this new study, Sibert and co-author Leah Rubin, who was an undergraduate student at the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, Maine at the time of the research, analyzed sediment cores taken many years ago by deep-sea drilling projects at two different sites: one in the middle of the North Pacific, and one in the middle of the South Pacific.

"We picked those sites particularly because they are far away from land and they're far away from any influences of changing ocean circulation or ocean currents," Sibert said. In other words, they wanted to make sure that the changes in ichthyoliths they saw weren't due to other variables, such as the migration of sediments across the ocean.

Related: How long do species last before they go extinct?

However, only the South Pacific site had data from 19 million years ago. The other sediment core had data from 22 million to 35 million years ago and from 11 million to 12 million years ago, but nothing in between. (These earlier and later cores still helped the researchers understand what fossils were present long before and long after that time period.) After extracting the ichthyoliths from the sediment cores, the researchers examined two specific metrics: abundance and diversity of shark fossils.

Extreme decline

By looking at before-and-after snapshots in the sediment cores, the researchers found that open-ocean shark fossil numbers dropped by 90% around 19 million years ago. But to understand whether this was truly an extinction, the researchers wanted to understand if diversity — the number of different shark species — also declined.

To measure diversity, they classified 798 denticles from the South Pacific and 465 from the North Pacific into 80 different morphologies, or shapes and structures. They found that around that time, about 70% of denticle types disappeared. The researchers also put together a catalog of modern shark denticles and found that another 20% of those pre-extinction event morphologies were present in modern sharks but not in the fossil record.

In other words, this lost extinction event wiped out between 70% and 90% of shark species and 90% of individual sharks.

Related: The 5 mass extinction events that shaped the history of Earth

"Frankly, we're shocked that this time period had such a dramatic event," Sibert said. The disappearance of sharks greatly altered the marine communities, disrupting 45 million years of stability, she added. In fact, the last time the marine vertebrate community had such a shake-up was 66 million years ago, in the late Cretaceous period, when an asteroid wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs.

"I think what has been the most surprising is just how extreme" the decline in shark diversity and abundance truly was during this time period, Rubin, who is now an incoming doctoral student at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, told Live Science in an email. The "million dollar question" is, what caused it?

No clear environmental driver, such as a major change in climate, accounts for this significant decline in sharks. And predators probably didn't drive sharks to extinction, as this die-off occurred several million years before tuna, billfish, seabirds, beaked whales and even migratory sharks exploded in numbers.

"We really, truly don't know" what caused the extinction, Sibert said. "This paper is just the very beginning of what I hope is going to be a really interesting next decade trying to figure out more about what happened at this time."

Missing fossils

Romain Vullo, a paleontologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) at the Géosciences Rennes, in France, who was not part of the study, said the findings were surprising. They can't be explained by a known global climate event at the time, and the extinction isn't seen in the global fossil record of sharks, he told Live Science in an email.

Still, "further data from other regions in the world would be required to confirm the interpretation of the authors," he added. Though two sites were analyzed, only the sediment core from the South Pacific specifically pointed to this 19-million-year-old extinction event and decline in abundance. It's possible that the data may reflect local changes and not a global extinction event, he said.

Sibert said it's possible but unlikely that it would be a local change. "While we don't have good data from this very specific time interval all over the world, we do have a lot of 'before' extinction snapshots and 'after' extinction snapshots from all over the world," she said. "Before the extinction, there are lots of shark scales, and after, there are not."

If this were a local phenomenon, a lot of shark fossils would be found in sediments that date back younger than 19 million years old, but they aren't, she said. "They're missing pretty much everywhere that we have looked," Sibert said.

However, "it is possible that this extinction was strongest in the open ocean environment, and not in the coastal environment," she added. The next steps are to figure out if species along the coasts, as well as other groups or ecosystems, were also greatly affected, she said.

Modern sharks, ancient lessons

One reason this shark tale wasn't told until today is that this time period, from 18 million to 20 million years ago, is mostly missing in sediment cores. It's not clear why this time period is hard to come across in the sediment record. It could have something to do with the extinction event, or it could just be "random happenstance," Sibert said.

Related: 6 extinct animals that could be brought back to life

It's puzzling that "this event in the early Miocene seems to have been hiding in an interval of geologic time that was previously unremarkable," Catalina Pimiento, a vertebrate paleontology researcher at the University of Zurich and Swansea University in the U.K. and Nicholas D. Pyenson, a research geologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and affiliate curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke museum in Seattle, Washington, wrote in an accompanying perspective piece published in the journal Science. Neither of them were involved in the study.

"Our view of the ancient oceans is constrained by the environments recorded in the rock record, which are often limited to shallow-water deposits that provide little insight into the oceanwide history of pelagic [oceanic] faunas," they wrote.

And, it turns out, this ancient story has modern parallels.

In the past 50 years, shark numbers have declined by more than 70%, due to overfishing and other human pressures, including climate change warming the oceans. One-quarter of shark species that exist today are currently threatened with extinction, according to the perspective piece.

"The parallels between this ongoing crisis and the extinction of pelagic sharks more than 19 million years ago thus feels like déjà vu, except that this time, we know that the decline of sharks is happening at a faster rate than at any other in the history of the planet," Pimiento and Pyenson wrote.

Sharks and other marine predators play an invaluable role in keeping the ocean ecosystem balanced. "These big changes in large marine organism populations and diversity can have knock-on effects that can really change the ecosystem forever," Sibert said.

The Miocene extinction event "fundamentally changed and really disrupted the whole ocean ecosystem and caused it to flip into an entirely new state," Sibert said. Sharks have not recovered in diversity or number from this major extinction event that seemed to have occurred 19 million years ago. Now, Sibert said, we're once again at a "tipping point."

Originally published on Live Science.

Editor’s Note: This article was updated to correct a sentence about shark species numbers. One quarter of all shark species are currently threatened with extinction, and there's a "substantial risk status increase" for the 31 species of oceanic sharks, according to the perspective.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus