6 mysterious structures hidden beneath the Greenland ice sheet

Nearly 2 miles thick in places, the ice sheet hides a landscape of canyons, mountains, fjords and gem-like lakes.

Fridtjof Nansen, the leader of the first expedition to cross Greenland, once described what he found in the Arctic as "the great adventure of the ice, deep and pure as infinity." Nansen, who made his journey in 1888, could not have known of the wonders hidden below the icy landscape beneath his skis.

Today, thanks to radar and other technologies, the part of Greenland that sits below its 9,800-foot-thick (3,000 meters) ice sheet is coming into focus. These new tools reveal a complex, invisible landscape that holds clues to the past and future of the Arctic.

The world's longest canyon

The Greenland ice sheet hides the longest canyon in the world.

Discovered in 2013, the canyon stretches 460 miles (740 kilometers) from the highest point in central Greenland to Petermann Glacier on the northwest coast. That's significantly longer than China's 308-mile-long (496 km) Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, the longest canyon on the planet that you can actually see.

The canyon plunges up to 2,600 feet (800 m) deep in places and is 6 miles (10 km) wide. For comparison, the Grand Canyon in Arizona averages about 1 mile (1.6 km) deep and 10 miles (16 km) across.

Parts of the canyon may route meltwater from beneath the ice sheet to the sea. It probably formed before the ice sheet and was once the channel for a mighty river.

Invisible mountains

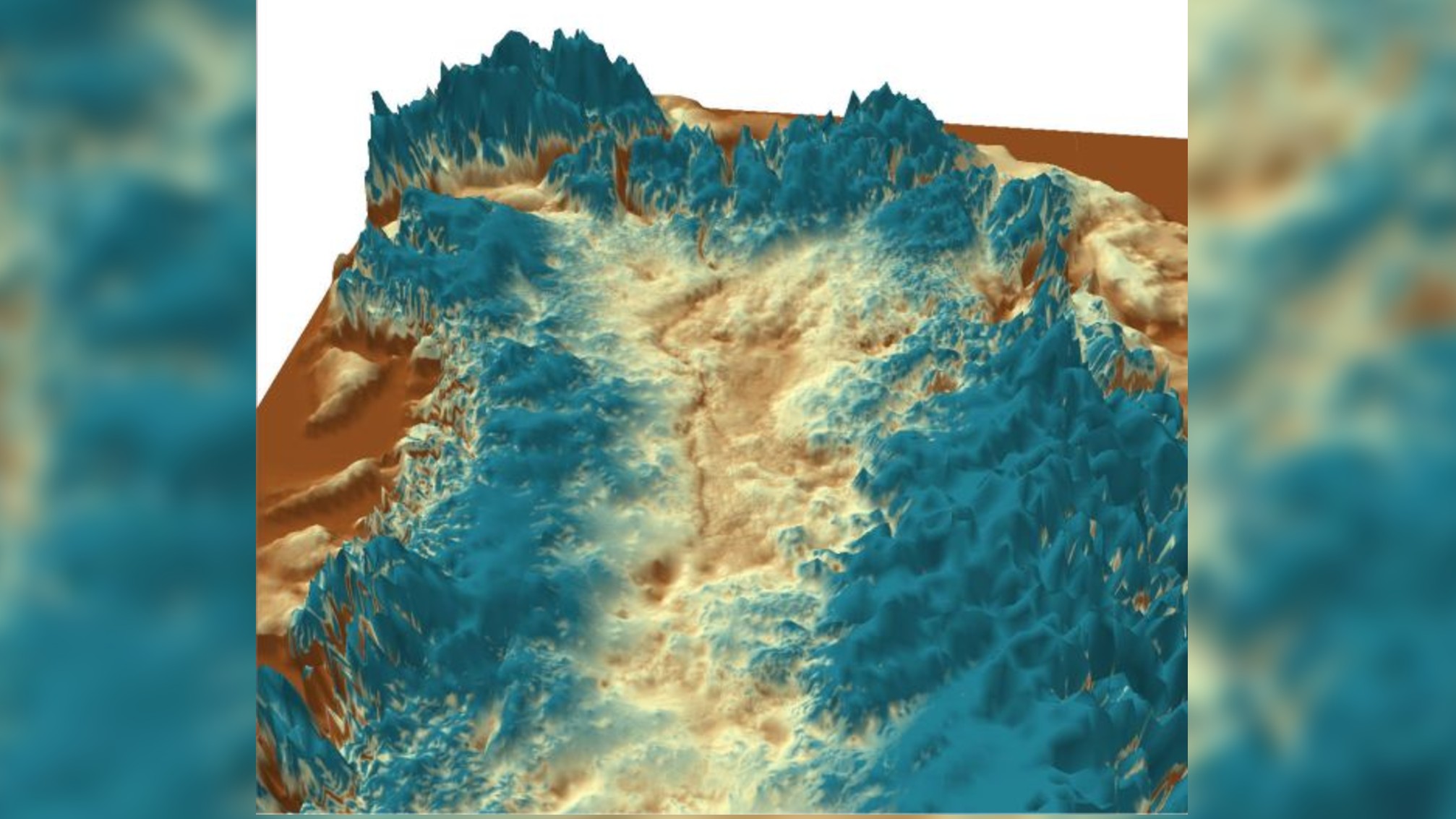

The canyon isn't the only rugged part of Greenland's under-ice landscape. Decades of mapping the island by ice-penetrating radar (which is usually mounted on airplanes) have revealed rugged mountain ranges and plunging fjords beneath the ice sheet.

A 2017 map of Greenland stripped of its ice shows a bowl-like depression in the center of the island. A circle of coastal mountain ranges rings this depression. The map revealed the topography underlying Greenland's flowing glaciers, which can help scientists predict how fast the glaciers will move in warming conditions and how quickly they will calve icebergs into the ocean.

A primeval lake

Hundreds of thousands or millions of years ago, before Greenland was covered with ice, it was home to a lake the size of Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

Today, the lake is a depression filled with sediment. But it was once filled with water 800 feet (250 m) deep in some places. The lake basin covers 2,700 square miles (7,100 square km) and was fed by at least 18 different streams.

The lake bed could hold valuable clues to the climate of the Arctic in the distant past, though discovering these secrets would require drilling through the 1.1 miles (1.8 km) of ice that now caps the ancient site.

Hidden gems

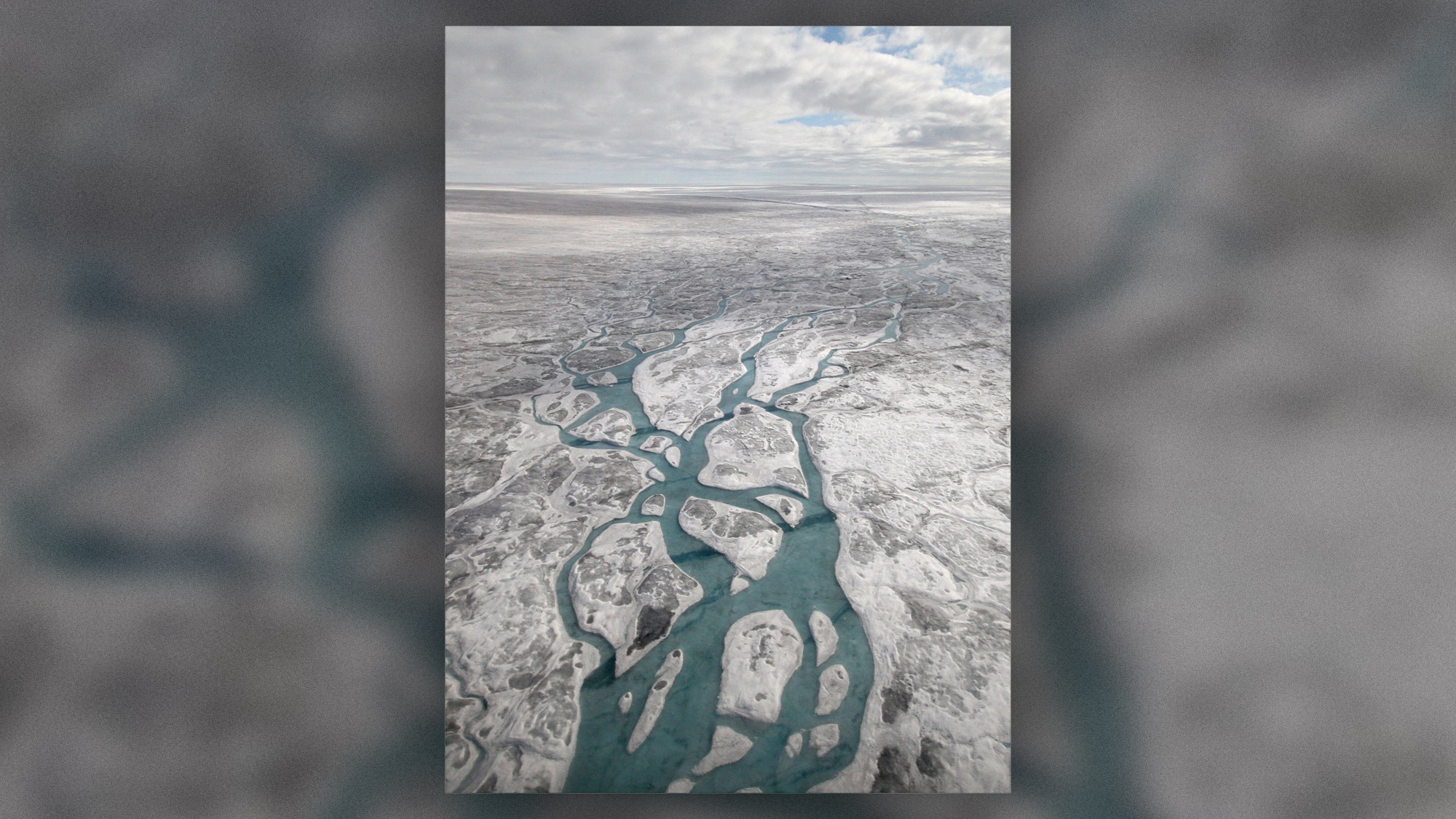

Greenland's ice sheet also hides a landscape of jewel-like lakes filled with crystalline meltwater. There are at least 60 of these small lakes, mostly clustered in northern and eastern Greenland, Stephen Livingstone, a senior lecturer in physical geography at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom and co-researcher of a study into the lakes, Live Science previously reported.

The lakes range in size from 656 feet (200 m) across to 3.7 miles (5.9 km) across. The meltwater in these lakes may flow from the surface of the ice sheet, or it may melt because of friction from the movement of ice or geothermal energy from below.

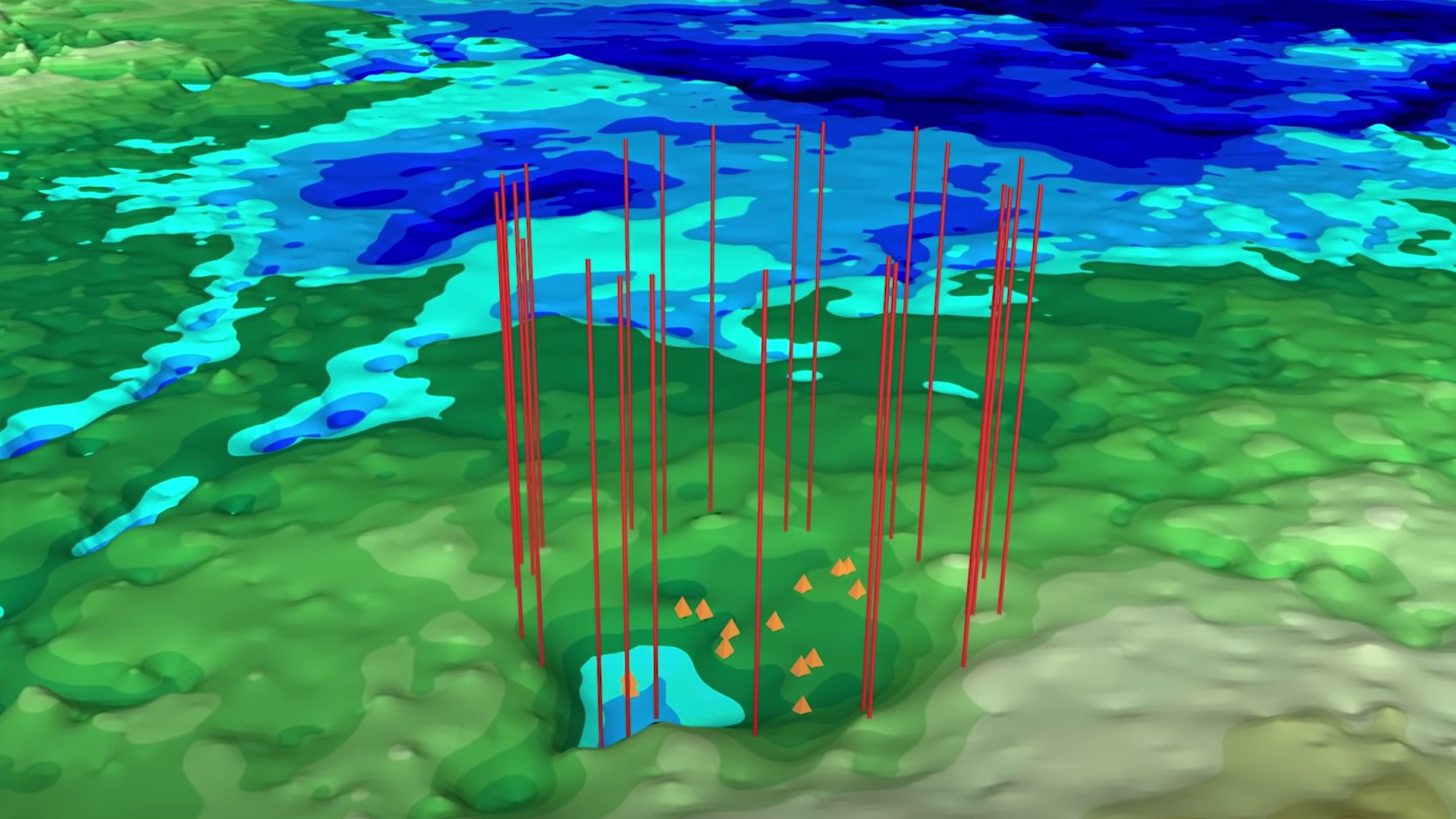

Evidence of meteor impacts

Not all the topography below the ice sheet is of Earthly origin. Scientists have found at least two likely meteor craters buried beneath the ice. Both are in northwest Greenland: One sits below Hiawatha Glacier, while the other is 114 miles (183 km) away from the first. The Hiawatha crater sits under about a half-mile (930 m) of ice, while the second crater is buried under 1.2 miles (2 km) of ice. The second crater is 22 miles (36 km) across, making it the 22nd-largest impact crater ever found on Earth. The first is a bit smaller at 19 miles (31 km) across.

Perfectly preserved fossil plants

An ice core dug up during a Cold War-era attempt at building a nuclear weapons base was rediscovered in a freezer in 2017 and found to hold the perfectly preserved fossils of plants dating to a million years ago.

"The best way to describe them is freeze-dried," Andrew Christ, lead author of a study into the core and a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer in the Department of Geology at The University of Vermont in Burlington, told Live Science at the time. "When we pulled these out and put a little water on them, they kind of unfurled, so they looked like they died yesterday."

The core came from northwestern Greenland, and the plants held within may have grown in a boreal forest. Such a forest could only grow in largely ice-free conditions, suggesting that parts of Greenland's ice sheet may be younger than researchers previously believed.

Originally published on Live Science

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

![A family portrait of galaxies from the CRISTAL survey. Red shows cold gas traced by ALMA’s [CII] observations. Blue and green represent starlight captured by the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/eVukmgPN8vVBokz2SrUwMV.png)