Webb space telescope has just imaged another most-distant galaxy, breaking its record after a week

And it almost certainly won't be the last time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

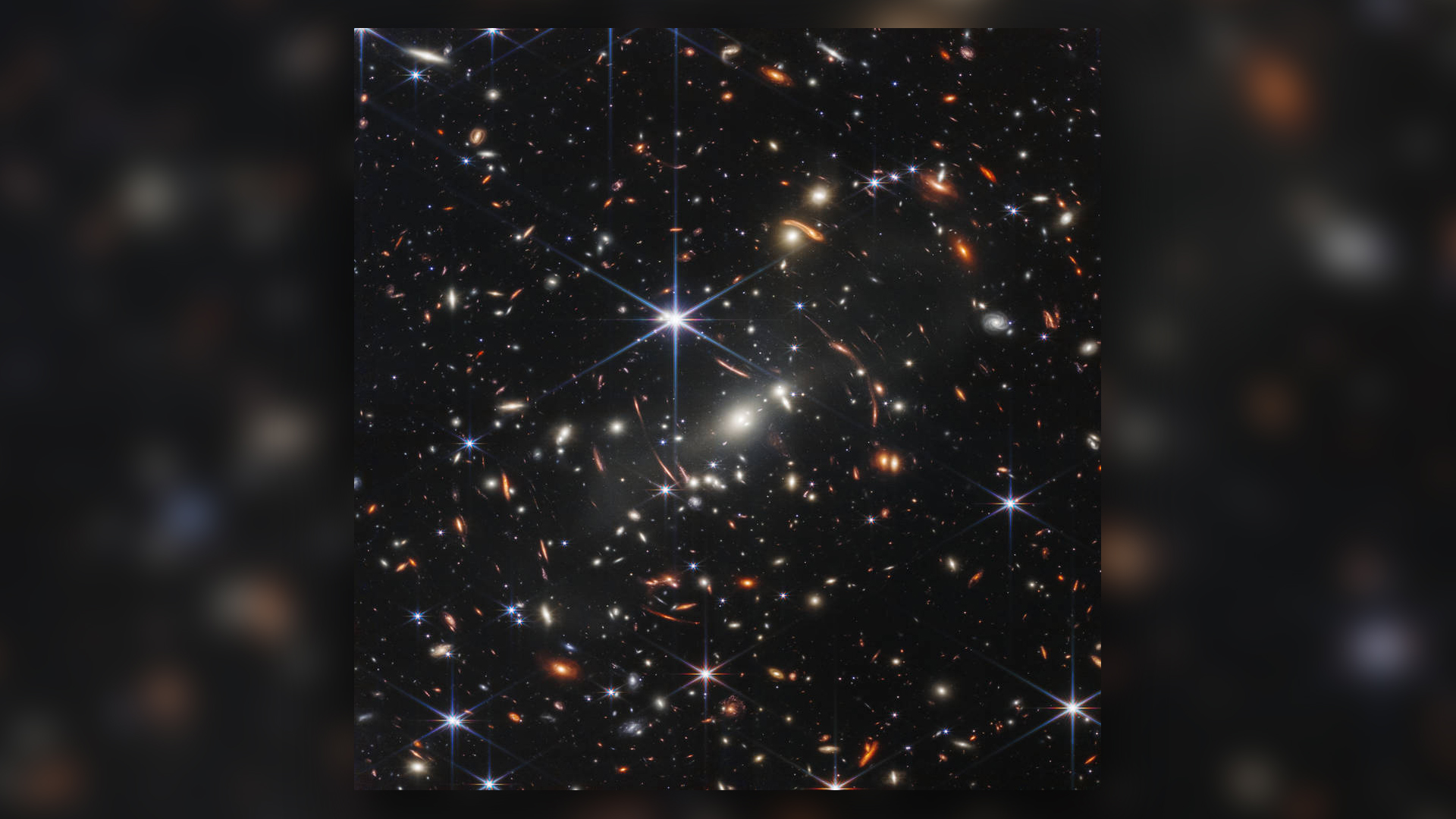

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have spotted what they think may be the farthest galaxy ever seen — a distant red smudge 13.5 billion light-years away.

The galaxy, named CEERS-93316, was pictured as it existed just 235 million years after the Big Bang, using Webb's Near Infrared Camera, which can peer back in time to the earliest flickerings of the very first stars.

The new result, which is still preliminary and has yet to be confirmed by studying the spectra of the galaxy’s light, has already broken a previous provisional record set by the telescope just one week ago, when another team spotted GLASS-z13, a galaxy that existed 400 million years after the Big Bang.

Related: See the deepest image ever taken of our universe, captured by James Webb Telescope

Light has a finite speed, so the farther it has traveled to reach us, the further back in time it originated. The wavelengths of light from the oldest and most distant galaxies also get stretched out by billions of years of travel across the expanding fabric of space-time in a process known as redshift, making Webb's sophisticated infrared cameras essential for peering into the universe's earliest moments.

The researchers, who outlined their findings in a paper posted July 26 to the preprint database arXiv, found that the newly discovered galaxy has a record-breaking redshift of 16.7, which means its light has been stretched to be nearly 18 times redder than if the expanding universe wasn't moving the galaxy away from us. The findings have not yet been peer-reviewed.

Webb's extreme sensitivity to infrared frequencies means that it must be isolated from disruptive heat signals on Earth, and the telescope now rests at a gravitationally stable location beyond the moon's orbit — known as a Lagrange point — after being launched there from French Guiana atop an Ariane 5 rocket on Christmas Day 2021.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During the six months following Webb's launch, NASA engineers calibrated the telescope's instruments and mirror segments in preparation for snapping the first images. Their progress was briefly interrupted after the telescope was unexpectedly struck by a micrometeoroid sometime between May 23 and May 25. The impact left "uncorrectable" damage to a small part of the telescope's mirror, but this doesn't seem to have affected its performance, Live Science previously reported.

Since the telescope released its incredible first images on July 12, it's been flooding the web with photos of fascinating distant objects. The newly described record-breaking image was obtained during the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS) — a deep- and wide-field sky survey conducted by the telescope. .

Remarkably, the researchers who found the image weren't even looking for the most distant recorded galaxy. Instead, they were compiling a list of 55 early galaxies (44 of which had been observed previously) to investigate how bright they were at various points in time after the Big Bang — a measure that will give them important insight into the evolution of the young universe.

To confirm that the galaxy is as old as its redshift suggests it is, astronomers will use spectroscopy to analyze the magnitude of light across a range of wavelengths for all the galaxies Webb's Near Infrared Spectrograph instrument has found so far. This device uses tiny, 0.1 millimeter-long, 0.2 millimeter-wide adjustable mirrors that only let in light from target galaxies, tuning out background radiation so that astronomers can break down a galaxy's stars by color. This effort will not only reveal the age of the galaxies' light but also their chemical composition, size and temperatures.

Astronomers think the first stars, which were first born from collapsing gas clouds around 100 million years after the Big Bang, were composed mainly of lighter elements, such as hydrogen and helium. Later stars began to fuse these lighter elements to form heavier ones, such as oxygen, carbon, lead and gold.

Given the stunning rate of Webb's discoveries, along with its ability to look as far back as 100 million years after the Big Bang, it's highly unlikely that this is the farthest galaxy we will see. The telescope will probably break its own records a lot more in the coming months — and we can't wait to see more.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus