What's causing mysterious 'ice rings' to form in the world's deepest lake?

The culprit was swirling beneath the ice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The humongous, mysterious "ice rings" that pockmark the world's deepest lake during Siberia's winter and spring months may look like icy crop circles, but they're not due to alien activity, atmospheric conditions or even, as previously thought, methane bubbles percolating from the lake's bottom.

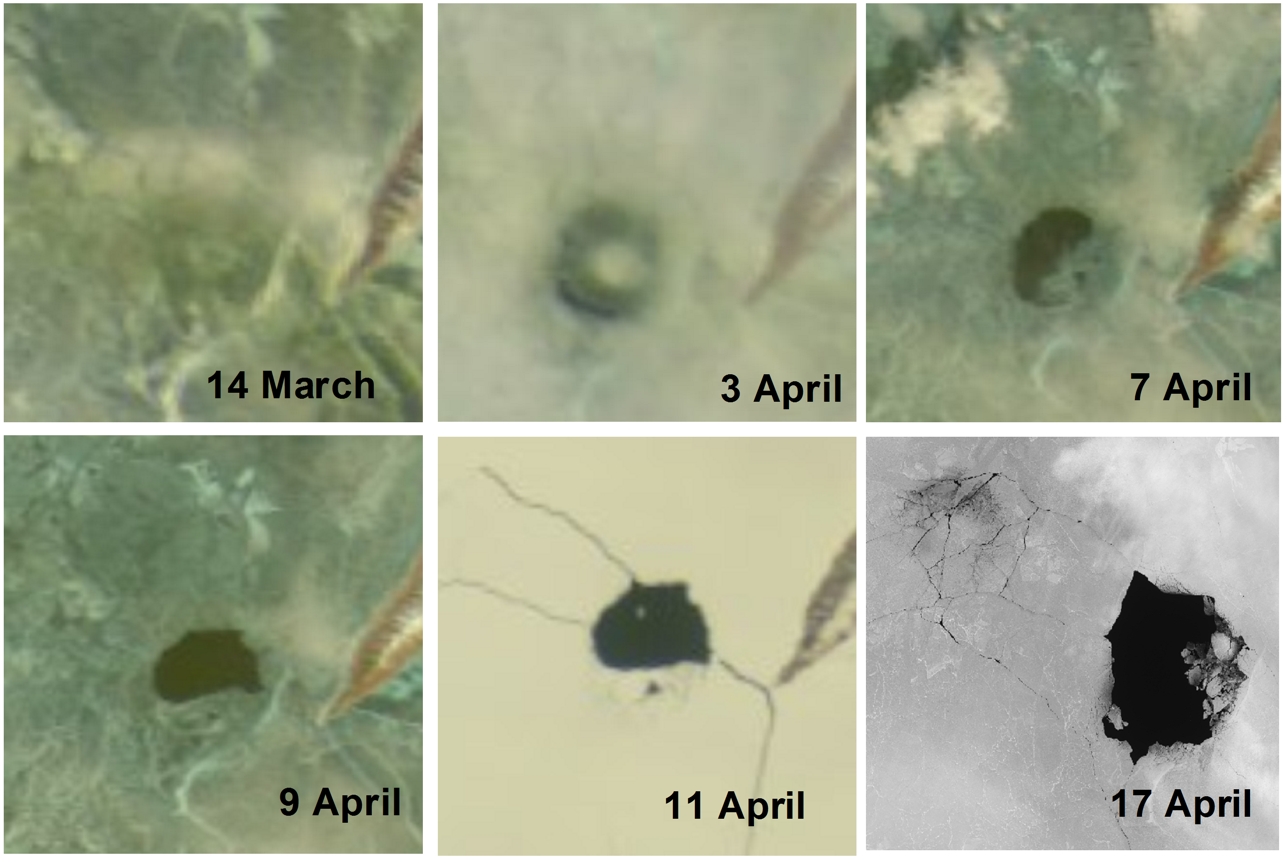

Rather, it appears that warm, swirling eddies of water under Lake Baikal's thick ice are responsible for these ice rings, some of which are up to 4 miles (7 kilometers) in diameter and can be seen from space, a new study finds.

Solving this mystery, however, wasn't an easy affair. An international team of researchers from France, Russia and Mongolia, who have studied the lake's ice rings since 2010, elected to travel to the lake biannually in 2016 and 2017 for a new study in which they drilled holes in the ice near the rings, and dropped sensors into the water below. One year, they heard that two vans had gotten stuck in the ice rings. One of them sank into the lake, and was never recovered.

Related: In living color: A gallery of stunning lakes

In Siberia's colder months, Lake Baikal — the largest freshwater lake in the world, by volume — freezes over. The ice is so thick, people routinely drive over it, said study lead researcher Alexei Kouraev, an assistant professor at the Laboratory for Studies in Spatial Geophysics and Oceanography (LEGOS) at the Federal University in Toulouse, France.

"It's a no-brainer," Kouraev told Live Science. "It's a very long lake, and if you want to go from one side to another, either you do 400 kilometers [248 miles] one way and then 400 kilometers on the other coast." But the trip across the ice is just about 25 miles (40 km), "so the choice is evident," he said.

However, while the ice is thick outside of and inside these rings of thin ice, the rings themselves can put vehicles and their occupants at risk, Kouraev said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fellowship of the ice rings

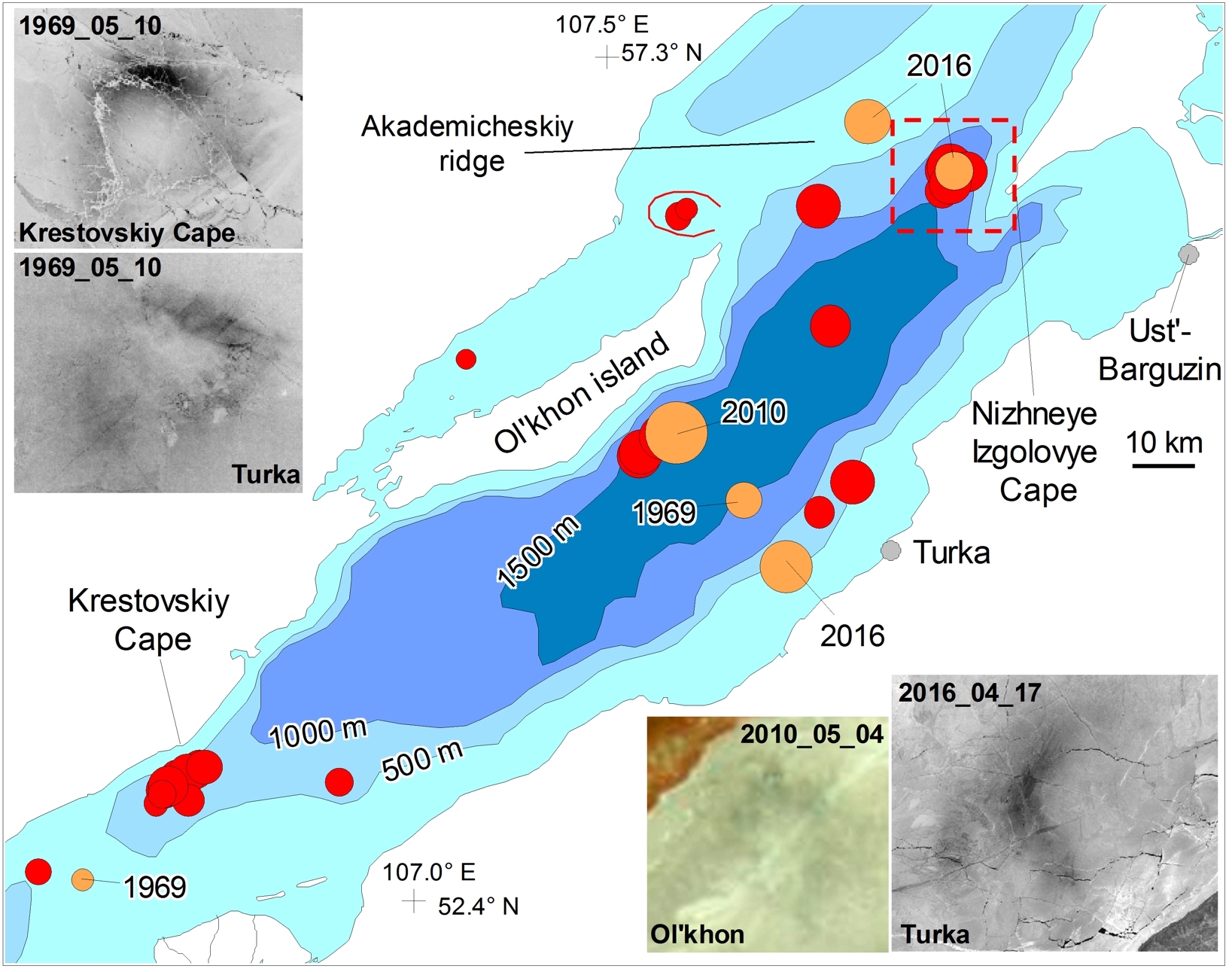

Ice rings have formed on Lake Baikal since at least 1969, and can last anywhere from days to months, satellite images show. However, these rings have unpredictable behavior, and show up in different parts of the lake from year to year. Moreover, they tend to appear in late April, but can crop up as early as January or as late as May, Kouraev said.

But scientists couldn't figure out how they formed. One of the more popular theories, indeed one that Live Science reported on in 2009, suggested that the greenhouse gas methane bubbles up from the lake's deep bottom to cause these rings. But Kouraev and his colleagues noticed that some of these ice rings formed in the lake's shallower waters, areas with no known gas emissions.

After analyzing data from the sensors they had dropped into the lake, the scientists found that the lake had warm eddies flowing clockwise under its ice cover. The currents weren't as strong at the center of the eddies, which explained why the centers of these rings still had thick ice, Kouraev said. However, the current at the edge of the eddies was strong, which explained why the ice on top of this edge was thinner, he said.

The sensors revealed that the water at these eddies was 2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 2 degrees Celsius) warmer than the surrounding water. What's more, the eddies had a lens-like shape, a phenomenon that is common in oceans but rare in lakes.

Related: In photos: Monster waves

But why did these eddies form in the first place? According to the sensors, which were kept underwater for 1.5 months at a time, as well as thermal-infrared satellite imagery, it appeared that the eddies formed each fall, before the lake froze over. Moreover, strong winds blowing in waters from the nearby Barguzin Bay could help them form, Kouraev said.

He noted that, so far, these ice rings have only been found in Lake Baikal, as well as the nearby Lake Hovsgol in Mongolia and Lake Teletskoye, also in Russia.

As for drivers who cross the frozen lake in their vehicles, Kouraev said that while cracks are easy to spot, the rings themselves can be harder to see at ground level because they're covered with ice. As a public service, Kouraev and his colleagues, who jokingly call themselves the Fellowship of the Ice Rings, have written booklets, given presentations and told Russia's national park service and ministry of emergencies about the rings. They also routinely update their website about the location of newly formed ice rings, which are visible in satellite images.

The study was published online in the journal Limnology and Oceanography in October 2019.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to note that the researchers have been working at the lake since 2010. Moreover, the vans that got stuck in the ice rings did not belong to the researchers.

- Album: Stunning photos of Antarctic ice

- In photos: The vanishing ice of Baffin Island

- In photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf through time

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus