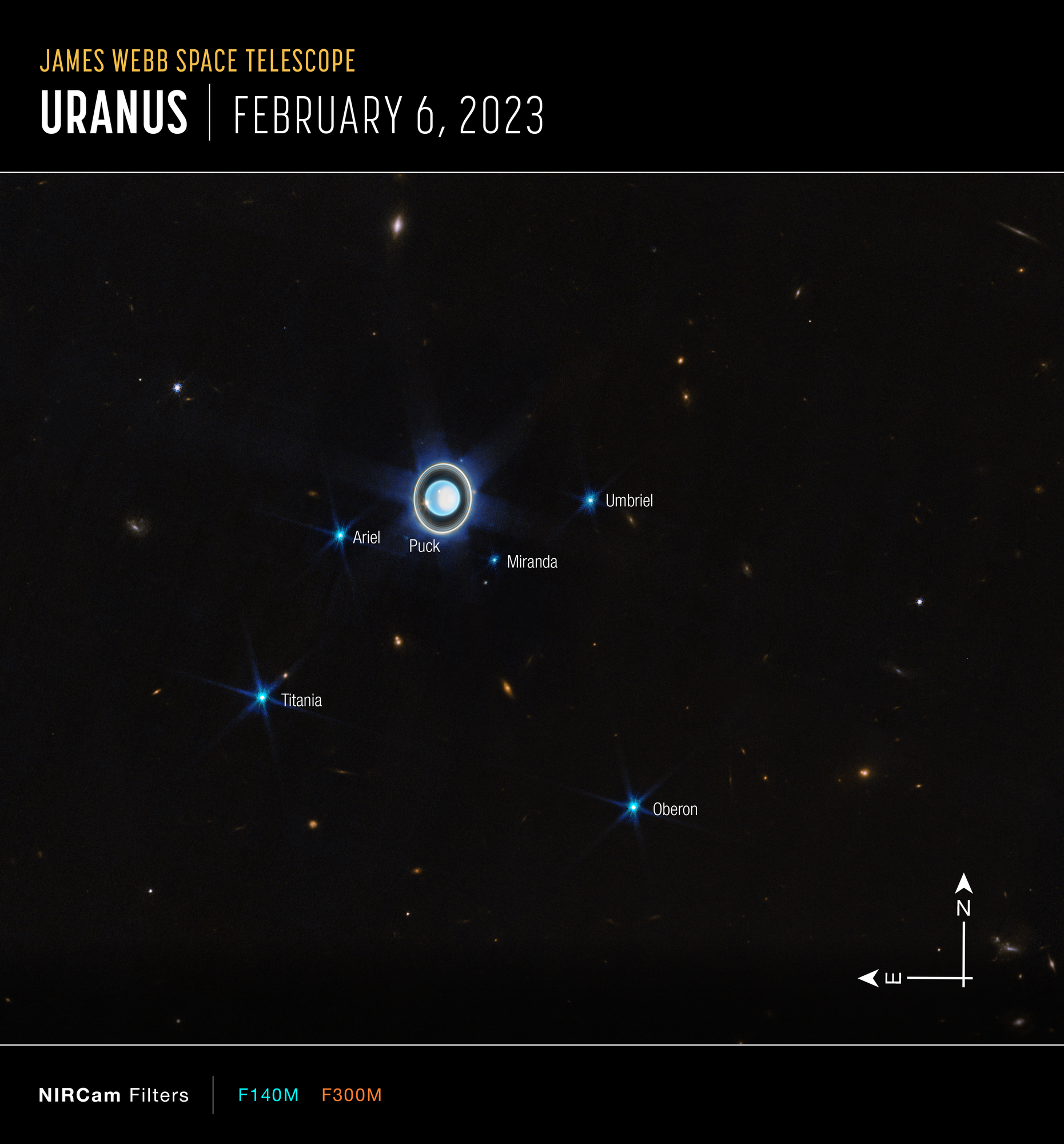

'Hidden' rings of Uranus revealed in dazzling new James Webb telescope images

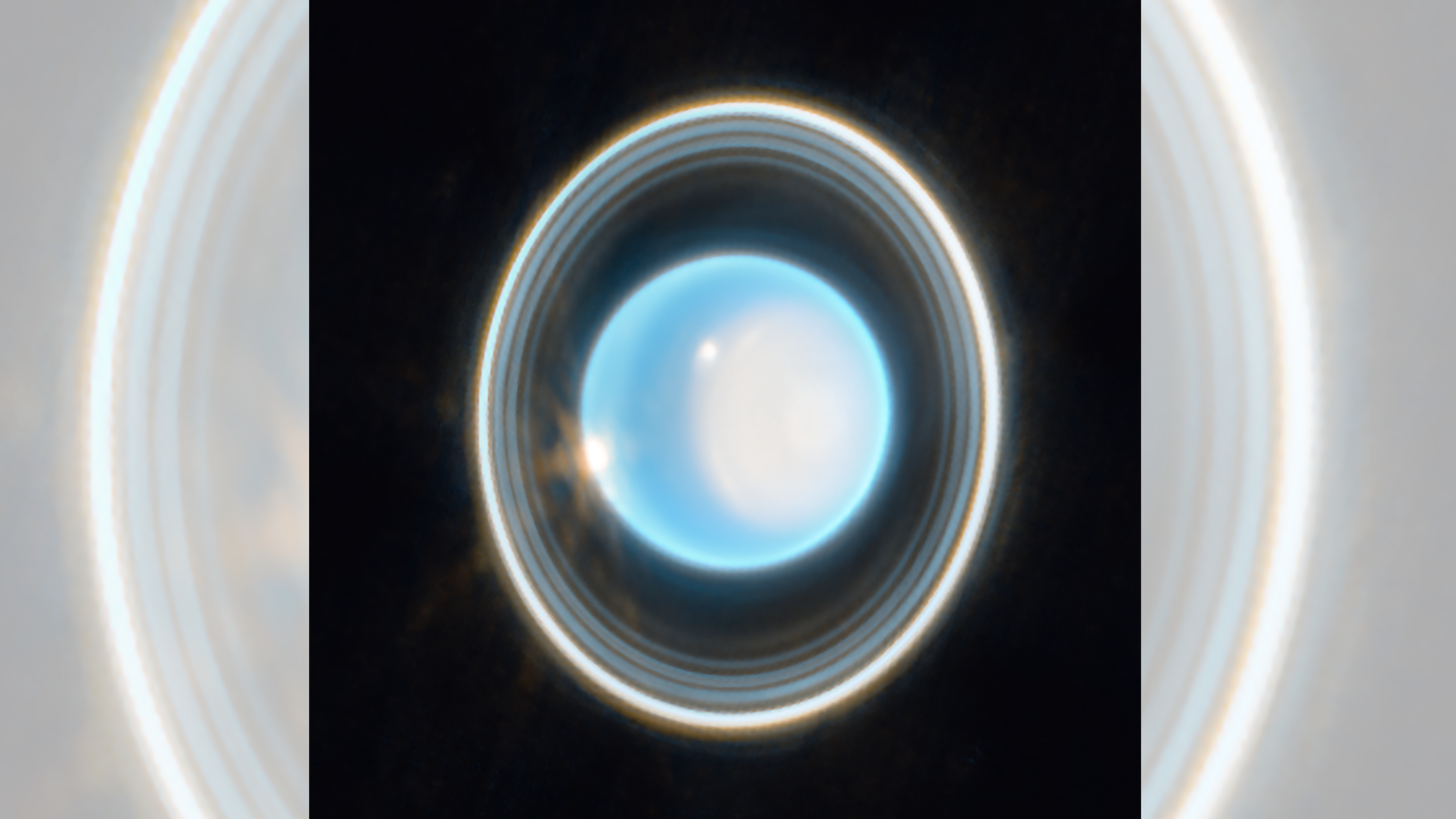

Astronomers zoomed in on the dusty rings around Uranus in a new series of stunning James Webb Space Telescope images.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have zoomed in on the faint and dusty rings around Uranus — and they are magnificent.

Located near the frigid edge of the solar system an average of 1.8 billion miles (2.9 billion kilometers) from the sun, Uranus is not often thought of as a ringed world, mainly because the icy planet is far too distant and faint to be seen from Earth with the naked eye. The same is doubly true for Uranus' 13 rings of ice and dust — most of which are so faint that astronomers couldn't confirm their existence until the Voyager 2 spacecraft made a close flyby of the planet in 1986, according to NASA.

Related: 35 jaw-dropping James Webb Space Telescope images

Even through the powerful lens of the JWST — which is already famous for peering across the cosmos into the oldest galaxies and black holes in the universe — only 11 of Uranus' 13 known rings are visible. The planet's two outermost rings are so faint that they were only discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2007, when the planet tilted in such a way relative to Earth that all its rings overlapped, according to NASA. It'll be another few decades before astronomers get another view like that; Uranus is the only planet that rotates on its side, rolling around the sun like a ball once every 84 years. That means Earth only gets to see the rare, edge-on view of Uranus' rings once every 42 years.

Uranus' unique orbit also means that its north pole — seen in this image as a bright region on the planet's right side — experiences many years of direct sunlight, followed by just as many years of total darkness. It's currently spring for Uranus' north pole, with summer scheduled to begin in 2028; meanwhile, the planet's south pole is angled off toward the darkness of space, totally invisible to Earth.

Last September, astronomers turned the JWST toward Neptune — Uranus' neighbor, and the most distant planet from the sun — to reveal that it too is surrounded by shimmering rings that are far too faint to see with the naked eye.

While they may look sheer and solid in telescope images like these, planetary rings are actually made of billions of fragments of icy rocks, some as large as boulders and others as tiny as dust motes. Scientists aren't sure how planetary rings form, but the process likely began around the same time as the solar system's formation, when our cosmic neighborhood was a chaotic collective of rocky chunks, according to the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus