Mammal cells use some viruses like vitamins, study hints

When added to mammalian cells, instead of activating inflammatory pathways as expected, one particular bacteriophage stimulated the cells to grow and survive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

On the menu tonight, a nice, nutritional, bacteria-killing virus. Sounds unappealing? It may not be to your cells.

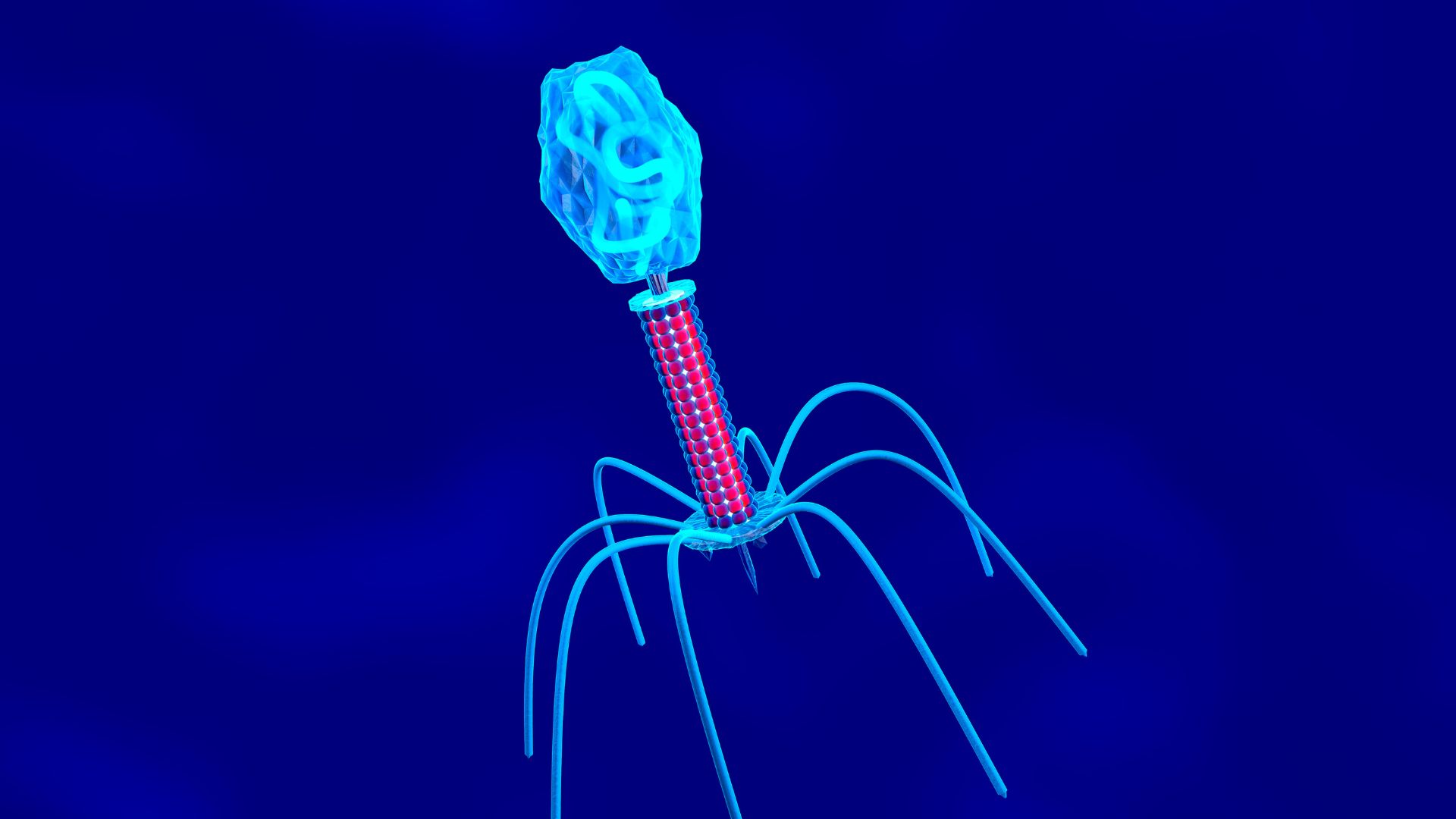

In a new study, scientists revealed that a type of bacteriophage — a virus that infects and kills bacteria — found in the human gut helps mammal cells grow and thrive in what could be a symbiotic relationship. That's a surprise, as other bacteriophages (phages for short) are known to trigger inflammatory responses when they encounter mammalian cells.

This phenomenon, described Thursday (Oct. 26) in the journal PLOS Biology, was only demonstrated in cells in the lab. However, the authors hope the findings will aid future research that could impact human health, such as supplementing studies investigating phage therapy to treat infections with antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

"[The study] opens up a new area of symbiosis and symbiotic interactions between phages and mammalian cells," senior study author Jeremy Barr, an associate professor of biological sciences at Monash University in Australia, told Live Science. "I think this study suggests that there may be a lot more that we're unaware of."

Related: Could bacteria-killing viruses ever prevent sexually transmitted infections?

Phages are the most abundant biological entities on the planet. They're extremely small, with most ranging in size from around 24 to 200 nanometers; to put that in perspective, a penny is about 19 million nanometers long. They're made up of a DNA or RNA genome surrounded by a protein shell. Although interactions between phages and bacteria are relatively well studied, the same can't be said for those between the former and mammalian cells.

In the study, the authors looked at a well-known phage species called T4 that normally infects Escherichia coli bacteria. They applied T4 to three types of mammalian cells in the lab: an immune cell called a macrophage that had been extracted from mouse tissue; and human lung and dog kidney cells derived from cancer cell lines.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The T4 phages didn't activate DNA-mediated inflammatory processes in the cells. Instead they triggered signaling pathways that promote cell growth and survival, resulting in increased cellular metabolism and the reorganization of actin, a protein that is found in the fluid-filled space inside mammalian cells. Actin reorganization is needed for cells to uptake material via macropinocytosis, a phenomenon also known as "cell drinking."

The broader health impacts of the study are still unknown, Barr said. The authors also only looked at one phage species, while estimates suggest there are as many as 10^15 phages in the gut). In addition, the results may be a side effect of using immortalized cancer cell lines, which are already more likely to grow and proliferate, he said.

Nevertheless, the find should spur follow-up research. Phage therapy is generally considered to be safe, although it's still early in the clinical trial process, and the current study now suggests that there's "many, many other potential impacts" that phages may have on human cells, Barr said.

Another avenue where the research could be applied is in the gut microbiome.

"There's some really interesting research showing that there's certain gut communities associated with inflammatory disorders — IBD [inflammatory bowel disease], Crohn's disease — that have virus signatures associated with them," Barr said.

"This is very much conjecture and extrapolation but it's interesting to think that maybe phages do play a role in this and there may be some inflammatory interactions, and maybe some also beneficial interactions in a more sort of homeostasis gut microbiome system," he said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus