3D-printed human brain tissue works like the real thing

The printed tissue grows and functions like that in a normal human brain, according to the authors of the new study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the first time, scientists have generated functional human brain tissue using a 3D printer.

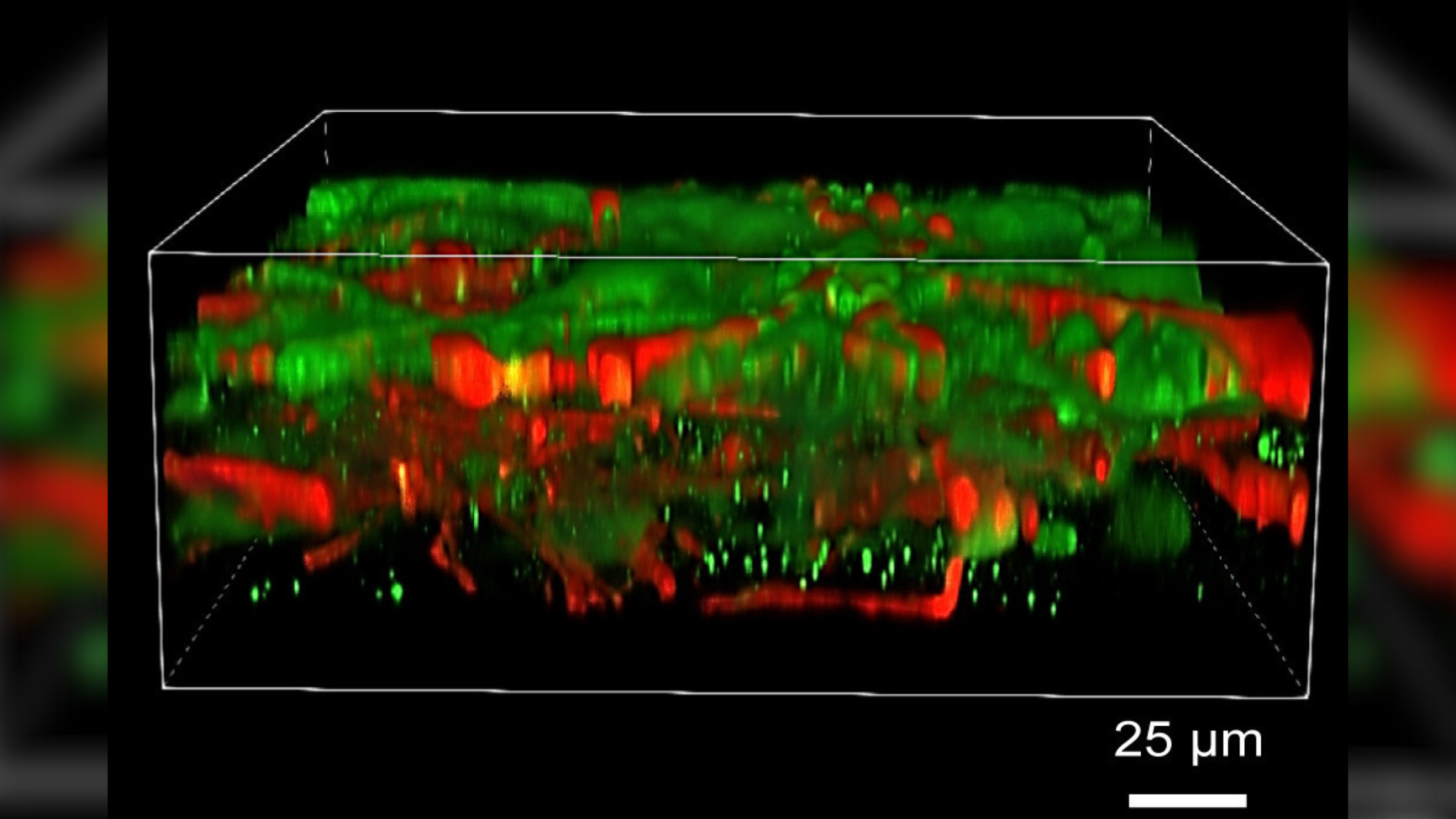

Scientists printed the tissue to be less than 0.01 inch (0.02 centimeter) thick, and it contains both nerve cells and supporting cells called glia. All of these cells can communicate with one another and form networks, as they would in a real human brain.

The tissue was created using a biological "printer" that churned out stem-cell-laden gel in horizontal layers. The stem cells were then coaxed to become brain cells with chemicals that stimulate this development. The tissue layers were carefully stacked, one by one, on a lab dish to form a complete tissue model.

The researchers behind the printed tissue described their accomplishment in a paper published Feb. 1 in the journal Cell Stem Cell. They hope it will complement other models of the human brain — such models, crafted from actual human cells, more accurately represent the intricate and unique features of the human brain than traditional animal models do. These include so-called brain-on-a-chip technologies, which mimic brain tissue on credit-card-sized devices, and cerebral organoids, which are miniature, simplified models of brains that self-assemble in dishes.

Related: How scientists 3D-printed a tiny heart from human cells

However, unlike organoids, the printing technique gives scientists more control over which cells end up where in the final tissue. Nerves within the printed tissue also form connections with each other within two to five weeks — a process that can take many months in organoids, Dr. Su-Chun Zhang, co-senior study author and a professor of neuroscience and neurology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told Live Science in an email.

Thanks to this speed, different versions of the 3D-printed brain tissue can also be made much more easily than organoids, Zhang said. This technology could therefore be particularly useful for testing new drug candidates for diseases that affect brain function, such as neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders, he added. That's because the different printed models could be made to display characteristics of each disorder.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists have previously tried to print human brain tissue. However, the neurons and glia within the final product couldn't form proper working connections with one another, the authors wrote in the paper. The new printing approach allowed networks to form because it used a gel that was soft enough to facilitate this process, allowing the cells enough give to reach out and connect. Plus, the gel had the added strength needed to still hold the layers of brain tissue together.

And unlike traditional 3D-printing approaches, which stack layers of material vertically, the authors stacked their gel horizontally. This allowed the layers to be thinner, and thus the cells within them were exposed to as much oxygen and nutrients as possible.

The printed stem cells developed into full-fledged neurons and glia, which formed networks resembling those found in the human brain, and they even communicated with each other via chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. The printed cells that normally belong to different parts of the brain — such as its outer layer, or cortex, and the striatum, which is involved in decision-making — also formed connections with one another.

The new model still has flaws, the authors acknowledged. For instance, the softness of the gel means it can't print multiple layers in one go, because they'd collapse if the gel weren't allowed to set in between. This slows the printing process. Individual layers are also limited in thickness because of the nutrient demands of cells within them, which consequently restricts the overall size of the tissue.

"A model is a model, not the real brain," Zhang said. However, the team is working to address these potential pitfalls and refine the technology going forward, he said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus