What happens to cancer cells when they die?

Cancer treatments aim to kill tumor cells, and the immune system is tasked with getting rid of the resulting cellular corpses.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Cancer treatments like chemotherapy kill tumor cells, often by pushing them to self-destruct, shrivel up and quietly die, or less commonly, by triggering a more explosive form of cell death.

But what happens to cancer cells after they die? Typically, the slain tumor cells are recycled in the same way that any other dead cell in the body would be.

When cancer cells meet their demise, their outer membranes usually become compromised. This happens in the "quiet" form of cell death, called apoptosis, a programmed process used to remove unneeded or damaged cells from the body.

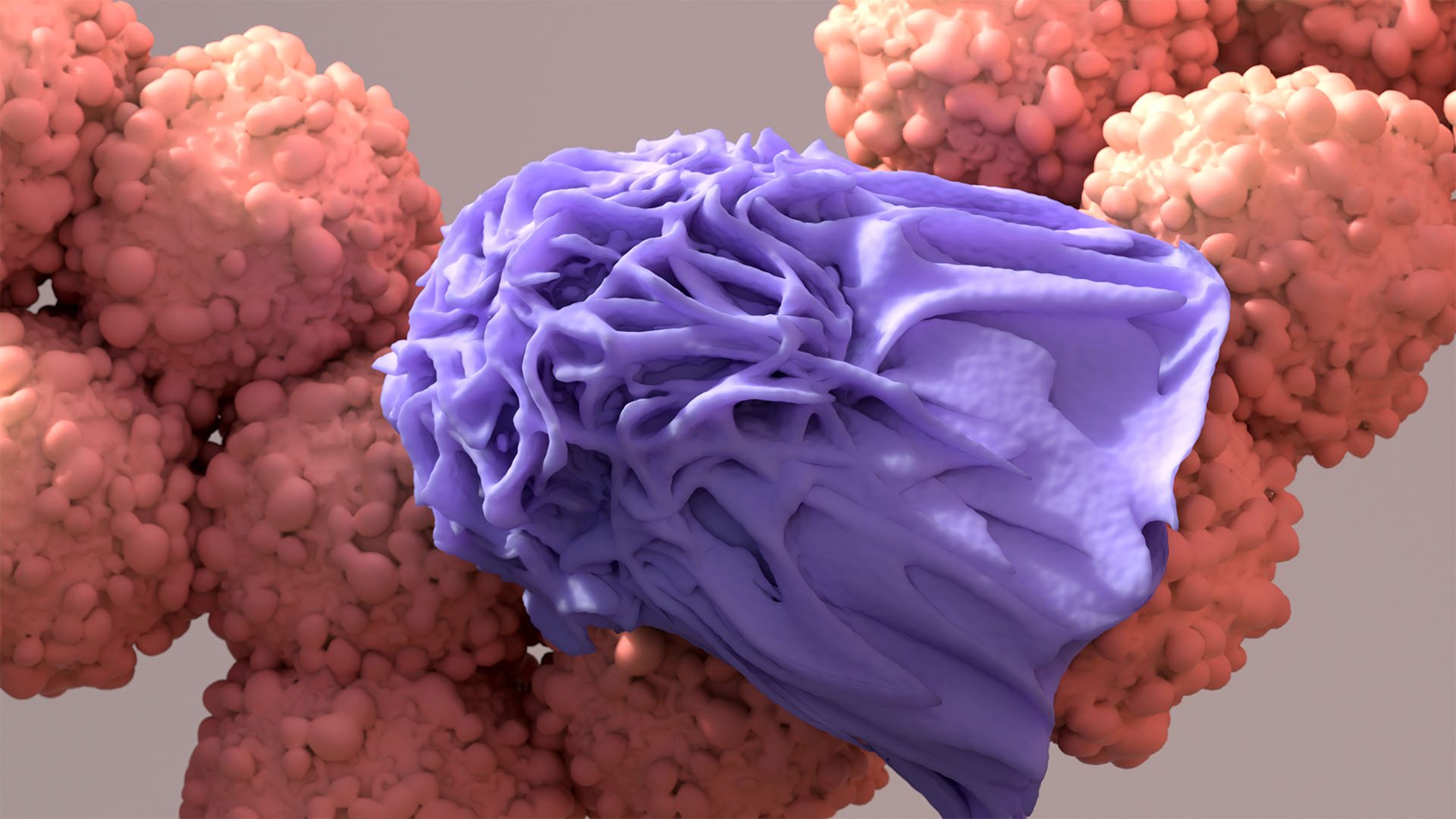

Once the molecular switches that trigger apoptosis are flipped "on," the dying cell shrinks and bits of its membrane break away in "blebs." This causes the cells' internal components to leak out and attract phagocytes, which are immune cells responsible for gobbling up cellular debris.

Related: The 10 deadliest cancers, and why there's no cure

The summoned phagocytes engulf the dead cancer cells and then break them down into smaller components, such as sugars and nucleic acids, the chain-like molecules found in DNA. Via this process, the dead cancer cells are recycled into components that can later be reused by other cells.

In the case of apoptosis — the type of cell death cancer therapies are traditionally designed to induce — bits of cancer cells are generally recycled in this way rather than excreted by the body, in urine, for example. Cancer therapies can sometimes also trigger other types of cell death, like necroptosis, the "explosive" form of cell death in which tumor cells swell and burst rather than shrinking. Phagocytes also efficiently gobble up this type of dying cell.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, dying cancer cells don't always go quietly. Studies suggest that, by releasing various debris that sparks inflammation, the cells can sometimes boost the growth of surviving cancer cells nearby.

This phenomenon, known as the Révész effect, may help explain how some cancers come back after treatment. It was first observed in the 1950s in mice with tumors. More recently, a 2018 study in mice and cells in lab dishes found that radiation and chemotherapy can trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokines, which are molecules released by immune cells that drive up inflammation and can sometimes support tumor growth.

Macrophages, a type of phagocyte, release these molecules in an attempt to fight the cancer, Dr. Dipak Panigrahy, a study co-author and assistant professor of pathology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston told Live Science.

A 2023 study conducted by a different group found that the control centers, or nuclei of dying cancer cells can sometimes swell and burst, thus spewing DNA and other molecules into their surroundings. In mice, these spilled molecules can accelerate metastasis, meaning the spread of cancer cells beyond their original tumor.

These studies help to shed light on how the death of tumor cells might contribute to cancer progression and relapse. However, the research is still in its relatively early stages and scientists don't yet understand the full implications of this link.

With more research, researchers aim to better understand the biological mechanisms underlying cancer and thereby develop more effective treatments for the disease.

For example, the 2018 study highlighted a way to counter the tumor growth driven by dead cancer cell debris: resolvins, molecules derived from omega 3 that can help reduce inflammation and the effects of cytokines while prompting the clearance of cell debris.

"The problem in cancer is that there are no therapies that stimulate the resolution of inflammation and down-regulate cytokines and clear debris," Panigrahy said. Resolvins could be one way of addressing those problems, their study suggests. That said, scientists are still unraveling exactly how and whether these molecules might help fight cancer.

The 2023 Nature study, on the other hand, pinpointed how living cancer cells recognize and respond to the signals transmitted by their dying peers. Blocking the dying cells' messages could potentially help prevent cancer from re-emerging after treatment, the study hints. More work is needed to know for sure.

Editor's note: This story was updated on June 18, 2024. It was originally published on Sept. 13, 2023.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Sarah Moore is a freelance science writer. She has an MSc in neuroscience and a BSc in psychology from Goldsmiths College, University of London. Sarah has experience in academic research and has worked in medical communications with top pharmaceutical companies. As a freelancer, she has contributed work to a wide range of publications. Sarah loves to write on all areas of science, from healthcare to nanotechnology but she is especially intrigued by the workings of the human brain.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus