'Bionic breast' could restore sensation for cancer survivors

Scientists are developing a new device that could help breast cancer patients who experience a loss of sensation after having a mastectomy.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists are developing "bionic breasts" that could restore sensation to breast cancer survivors who have undergone mastectomies and reconstructive surgeries.

Every year, more than 100,000 women in the U.S. have one or both of their breasts surgically removed to treat breast cancer and to help stop the disease from returning, or as a preventative treatment for those with a high genetic risk of breast cancer.

After a mastectomy, many patients opt to have reconstructive surgery to rebuild the breasts with implants or tissues from elsewhere in the body. However, there's only recently been an option to potentially restore the nerves of the chest and nipples as part of this procedure. Thus, many patients experience a loss of sensation in their breasts and a decline in sexual satisfaction that can negatively impact their mental health.

The new bionic breast, which would be implanted in the skin of the chest, is still being developed. However, the team has just received $4 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to start testing parts of the device in patients as early as next year.

"We're working hand in hand with our patients to take the best of science from across disciplines, as you can see, and solve a very fundamental but massively important problem that causes great human suffering," Dr. Stacey Lindau, a gynecologist and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago who is leading the research, told Live Science.

Related: Breast implants saved a man's life during a lung transplant. Here's how.

Lindau got the idea for the new project after hearing patients describe their experiences of recovering from reconstructive surgery following a mastectomy. Not only were their sex lives impeded afterward but also their everyday social interactions — for example, they could no longer feel the warmth and pressure of a hug from a friend, she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"My patients who know that I am also a researcher have asked me, can you please find a solution for this problem?" Lindau said. "The breasts are an important sexual organ for many women and their partners, and loss of sensation in the breast for some women is as distressing as it would be for a man to lose sensation in his penis, for example," she said.

When designing the new bionic breast device — which the researchers first described in a 2020 article in the journal Frontiers in Neurorobotics — the team drew inspiration from technology that had already been developed to restore sensation in patients with prosthetic hands.

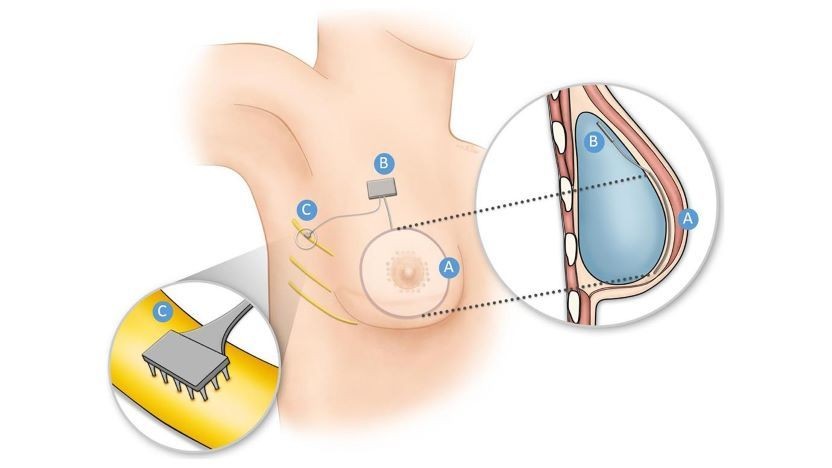

The idea is to insert artificial pressure sensors under the skin of the reconstructed breast. When stimulated by pressure, these sensors send signals to implanted electrodes under the arm that, in turn, stimulate "intercostal" nerves that run between the ribs. These nerves then relay the signals to the brain, where they are interpreted as sensation.

Over the next four-and-a-half years, Lindau and her team plan to use the NIH funds to conduct a proof-of-concept study in eight patients undergoing mastectomy and reconstructive surgery to confirm they can deliver electricity to the intercostal nerves via electrodes.

At the same time, bioengineers are developing the artificial pressure sensors from soft, flexible polymer materials that would feel similar to breast tissue, Sihong Wang, an assistant professor of molecular engineering and member of the team at the University of Chicago, told Live Science. They're also working on ways to ensure that the sensors wouldn't trigger a harmful immune response once they're implanted in the body.

If these efforts are successful, the team plans to combine the flexible sensors and the electrodes in a device that could be tested in patients, Lindau said.

Broadly, the effort may have potential applications beyond breast cancer survivors.

"We have every reason to believe that the work we're doing here could apply to many other health conditions where people suffer loss of sensory functions," Lindau said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus