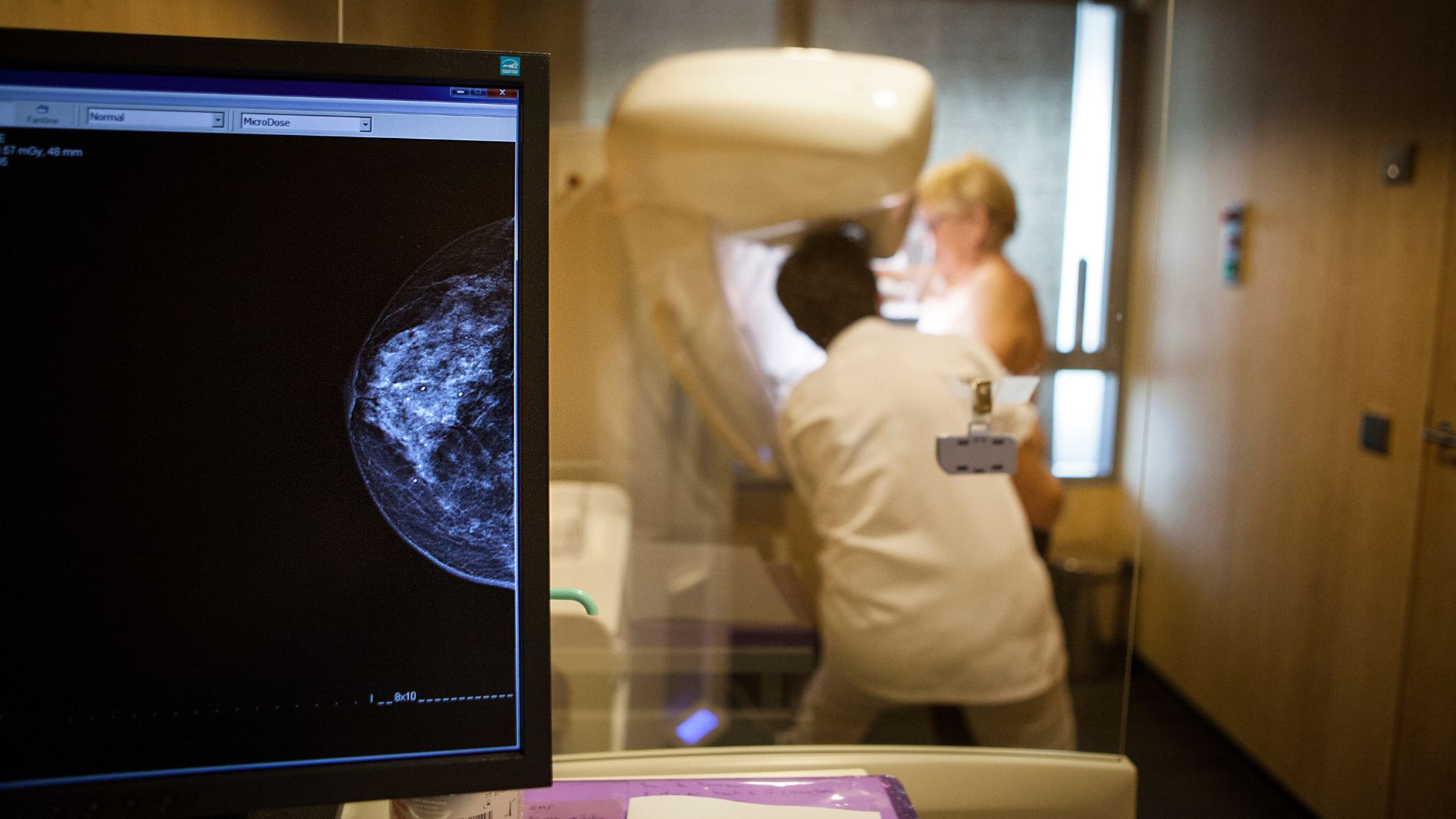

AI predicts 5-year breast cancer risk better than standard tools — but we aren't sure how it works

Artificial intelligence models can use breast imaging data to pinpoint those at highest risk of getting breast cancer in the next five years, better than a standard approach.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can pinpoint patients at highest risk of developing breast cancer in the next five years better than a standard risk assessment used in the clinic, a study suggests.

Doctors commonly predict a person's five-year risk of developing breast cancer using models that take into account the person's age, race, ethnicity, family history of breast cancer, and whether they've ever had breast tissue sampled for analysis, due to having suspicious lumps in their breasts. These models also take into account breast density, as assessed through mammograms.

However, "only about 15% to 20% of women who get diagnosed with breast cancer have a known risk factor, such as family history of disease or previously having a breast biopsy," Dr. Vignesh Arasu, first author of the study and a research scientist with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research in Oakland, California, told Live Science.

AI has helped radiologists identify hundreds of features in a mammogram that can aid doctors in diagnosing breast cancer, said Arasu. "I was interested in understanding how the same technology can help us understand future risk," he said.

Related: Breast cancer screening should start at age 40, expert task force says

In a study published Tuesday (June 6) in the journal Radiology, Arasu and his colleagues analyzed how well five AI models predicted which of 18,000 patients had the highest five-year risk of breast cancer. The analysis used data from patients who'd had mammograms in 2016 and were then monitored until 2021. Overall, about 4,400 of the participants developed cancer within the five years of their mammogram.

The models based their predictions on mammograms that, at the time taken, showed no visible evidence of cancer. While it remains unclear exactly how the AI models are predicting cancer risk from mammogram data, broadly, they link certain features and patterns in the breast tissues' structure with cancer risk, said Arasu.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers pitted these AI models against a commonly used assessment called the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) clinical risk model.

Patients with the highest AI risk scores, in the 90th percentile, accounted for 24% to 28% of the cancers that occurred within five years. By comparison, the highest BCSC scores captured only 21% of cancer cases. The AI models showed the biggest advantage over the BCSC model when predicting which patients were most likely to develop breast cancer within a year of their mammogram.

The findings suggest that "AI could be used alongside the traditional risk model" to predict future breast cancer risk, said Arasu.

In the clinic, people who AI predicts to be at highest risk of breast cancer could be screened more frequently to potentially catch cancers earlier, said Arasu. These high-risk individuals could also potentially be given preventative therapies, such as tamoxifen, which blocks estrogen in breast cells to decrease breast cancer risk.

As the study focused on a predominantly white, non-Hispanic population, further work is needed to establish how well the AI models might work for people of different races and ethnicities, said Arasu.

While "it is a very well conducted research study," another limitation is that it is unclear how the AI models may work for cancers of different severity, Adam Brentnall, a statistician who studies the prevention and early detection of cancer at Queen Mary University of London, told Live Science in an email.

For example, if the AI models are best at detecting small tumors that haven't yet spread, or metastasized, they may offer little benefit over standard risk models because the cancers' "prognosis and treatment would likely be the same," he said.

"On the other hand, if advanced cancers can be detected earlier by using the model to tailor screening or cancer prevention strategies, then clinical benefits might be large," said Brentnall.

"That's actually the focus of our next phase of research," said Arasu.

Scientists' current lack of understanding of how the AI models reach their conclusions could also make it hard to implement these systems in the clinic, since doctors may not be able to explain to patients how their risk is being assessed, said Brentnall.

Editor's note: This article was updated on June 12, 2023 to correct a typo and Dr. Vignesh Arasu's job title and affiliation. The article was first posted on June 6.

Carissa Wong is a freelance reporter who holds a PhD in cancer immunology from Cardiff University, in collaboration with the University of Bristol. She was formerly a staff writer at New Scientist magazine covering health, environment, technology, nature and ancient life, and has also written for MailOnline.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus