Biggest eagle to ever live plunged headfirst into dead prey to eat the organs

Its name in the Māori language means "old glutton."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The biggest eagle that ever lived hunted like its modern relatives but feasted like a vulture, new research shows.

The extinct giant, known as Haast's eagle, gripped and pierced living prey with its sharp talons and beak. But it ate its kills like a vulture would have, slashing into the carcass and inserting its head deep inside the body cavity to gulp down internal organs.

Scientists have long argued over whether Haast's eagle (Hieraaetus moorei) was a predator, like modern eagles, or a vulturelike scavenger. Its feet and talons resembled those of eagles. But vulturelike skull features hinted that it might be adapted to feed on animals that were already dead.

Researchers recently settled this question using digital models and simulations to compare the extinct giant with living birds. Analysis of the birds' skulls and talons pinpointed which feeding behaviors in the extinct raptor were like those of eagles, and which resembled vultures' habits.

Related: In photos: Birds of prey

Haast's eagles lived in New Zealand and weighed up to 33 pounds (15 kilograms), with talons that were 4 inches (9 centimeters) long and a wingspan that extended nearly 10 feet (3 meters) wide, according to the Wingspan National Bird of Prey Centre, a New Zealand conservation organization.

The giant eagles fed primarily on moas, large and wingless birds that are now extinct but were plentiful in New Zealand until about 800 years ago. Around that time, the Māori people arrived on the island and began hunting moas and destroying the birds' forest habitats, another team of researchers reported in 2014. Māori people called the massive eagle "te hōkioi" or "pouākai," which means "old glutton." But it was the human appetite for moas that doomed the eagles; as the moas dwindled across New Zealand, the eagles also vanished.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Preserved moa bones that were scarred by eagle beaks and talons show that Haast's eagles ate moas. But did the eagles prey on living moas, which could weigh up to 440 pounds (200 kg)?

Prior studies that analyzed the eagle's overall body shape and talon structure found similarities to the bodies and talons of eagles, hinting that Haast's eagle was a hunter. However, questions still lingered about vulturelike skull features "such as the bony scrolls around the nostrils, which couldn't be explained by a predatory lifestyle," said Anneke van Heteren, lead author of the new study and Head of the Mammalogy Section at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich.

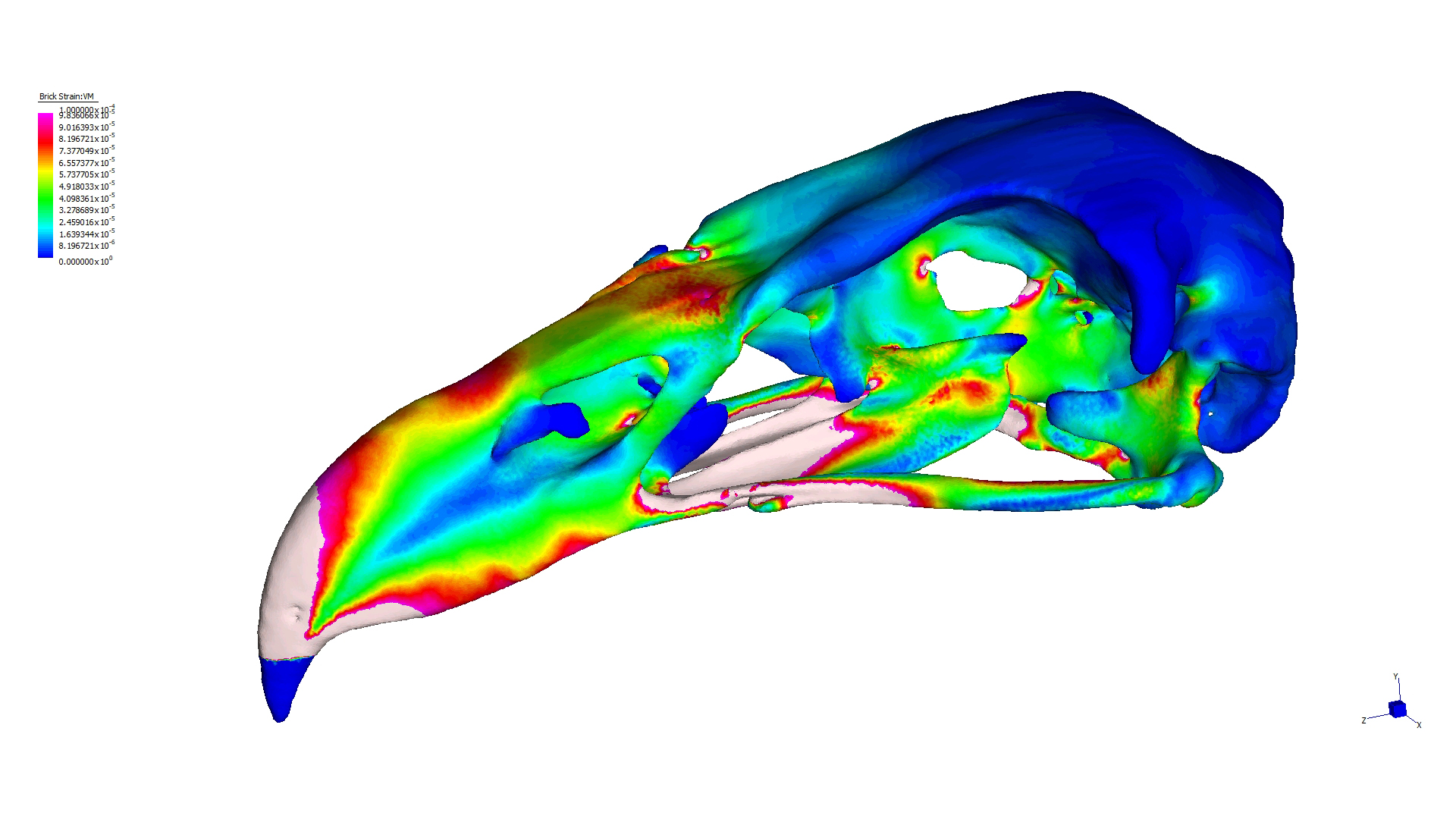

For the study, the scientists constructed 3D digital models of Haast's eagle skulls, beaks and talons, comparing them with the bones and talons of three eagle species and two vulture species. They modeled muscles and analyzed dozens of markers on the bones to determine which parts of the feet and skull were working the hardest as the extinct raptor hunted and fed.

"When you put certain forces on the skull, it slightly deforms, so you can look at how it bends during feeding or during hunting," van Heteren told Live Science. The researchers measured strain levels at several points on the skull, then compared those measurements to spots in the same locations across all the birds' skulls.

During certain behaviors, such as clutching prey in a death grip with their feet, the strain values for Haast's eagles resembled those of other eagles, van Heteren said. Its beak, with the potential to deliver a "death bite," was also very eaglelike, "but the neurocranium, which is where all [the] neck muscles attach — that was much more vulturelike," van Heteren said.

This suggested that while Haast's eagle did kill its massive moa prey, it ate them in the same way that scavenging vultures devour carrion, by inserting its head inside the corpse and then yanking and gulping down organs and strips of muscle.

"These moas weren't just dying from old age and then being eaten — they were actively hunted," said van Heteren. "But it was hunting these giant moas that were much larger than itself, which forced it to feed like a vulture would feed on an elephant carcass."

Haast's eagle may have shared something else in common with vultures: a bald head. Artistic representations of the extinct bird typically give it a feathered, eaglelike head and neck. However, in a Māori cave painting that is thought to be a Haast's eagle, the bird's body is colored while the head is not, "which we interpret as bald versus feathered," van Heteren said. "That really reinforces the idea that it was feeding like a vulture, with its head deep into the gooey organs of its prey."

The findings were published Dec. 1 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus