Frogs' skulls are more bizarre (and beautiful) than you ever imagined

A frog's head can be uniformly smooth on the outside, but spiky and weird on the inside.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

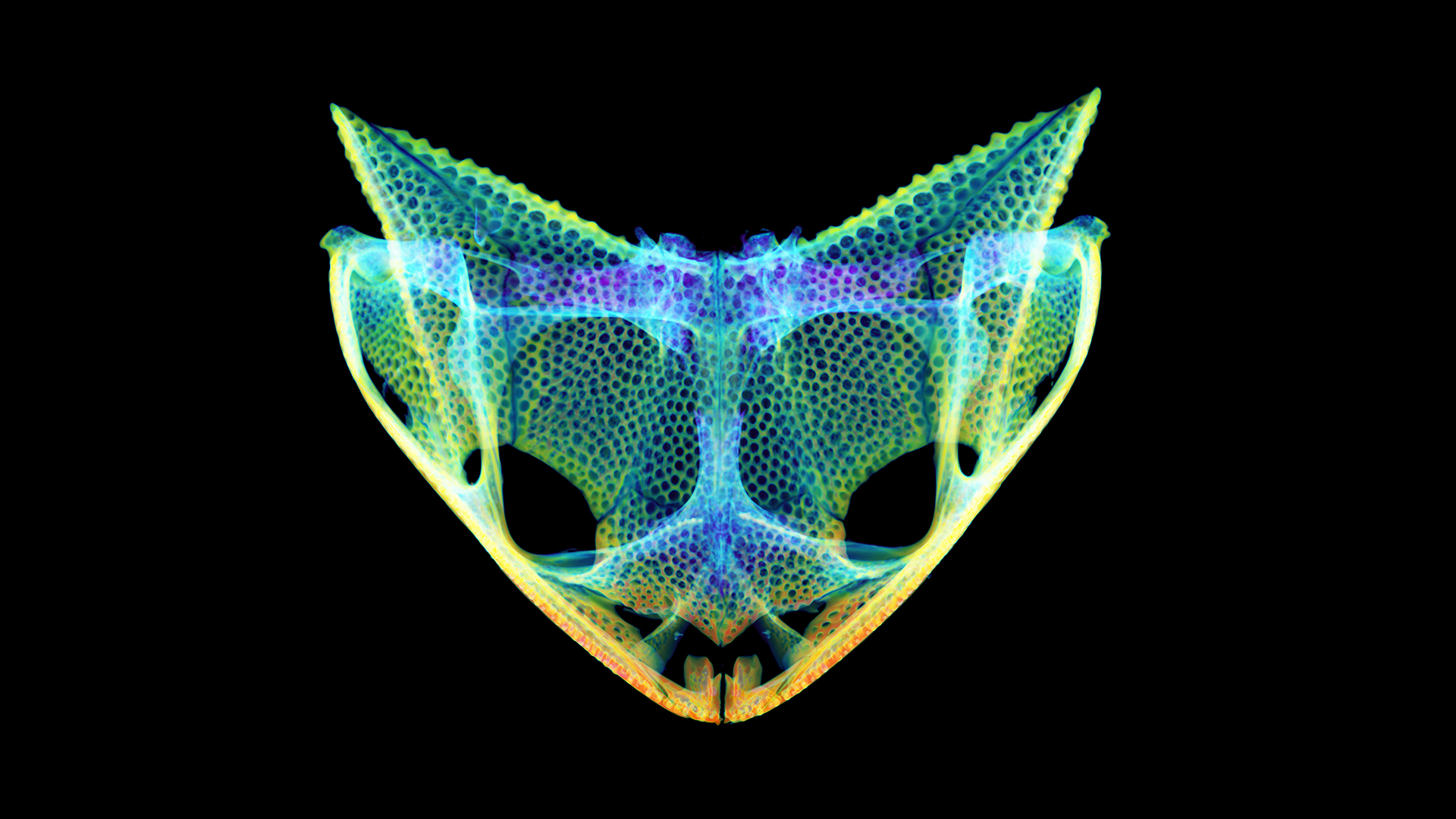

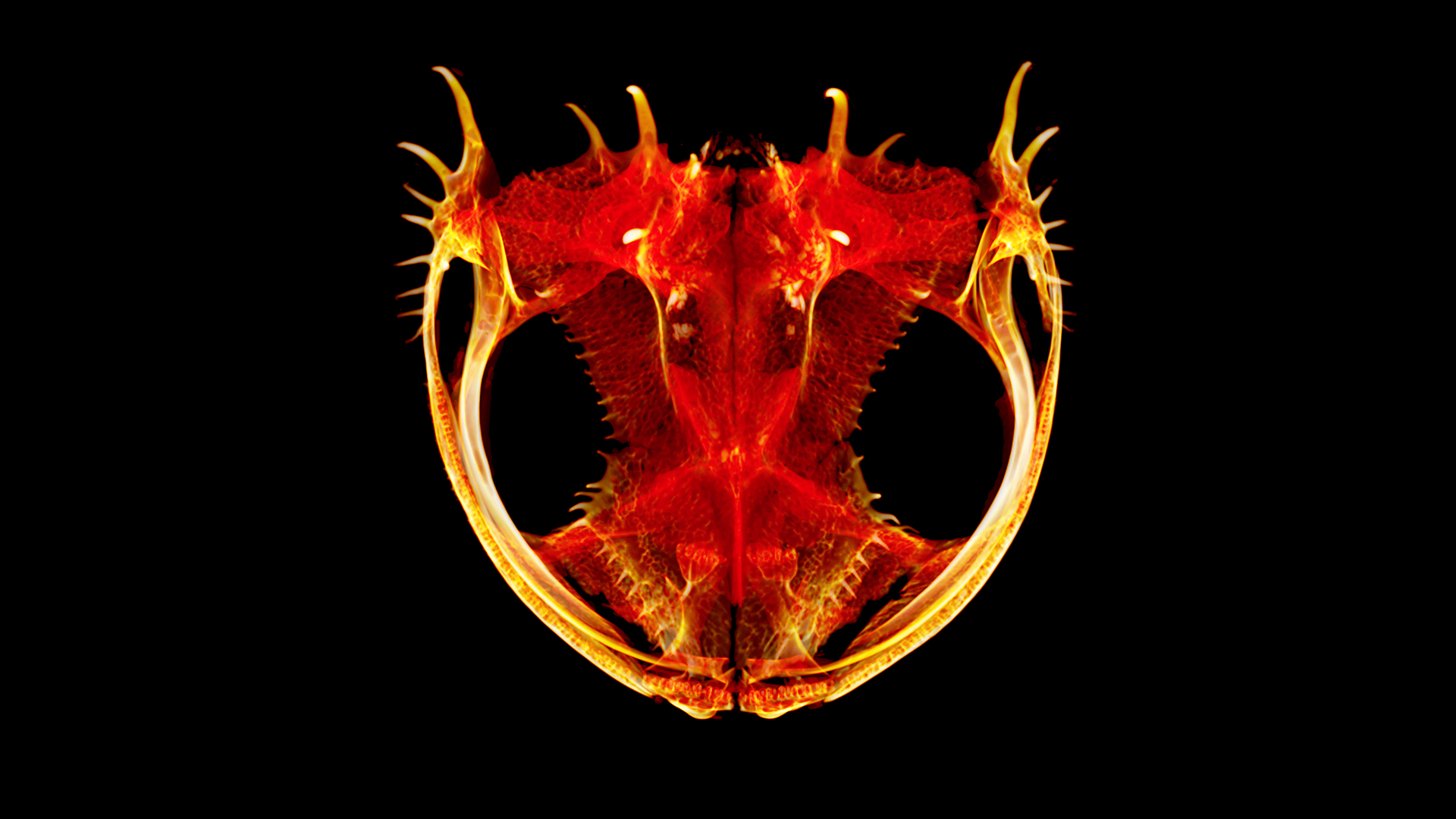

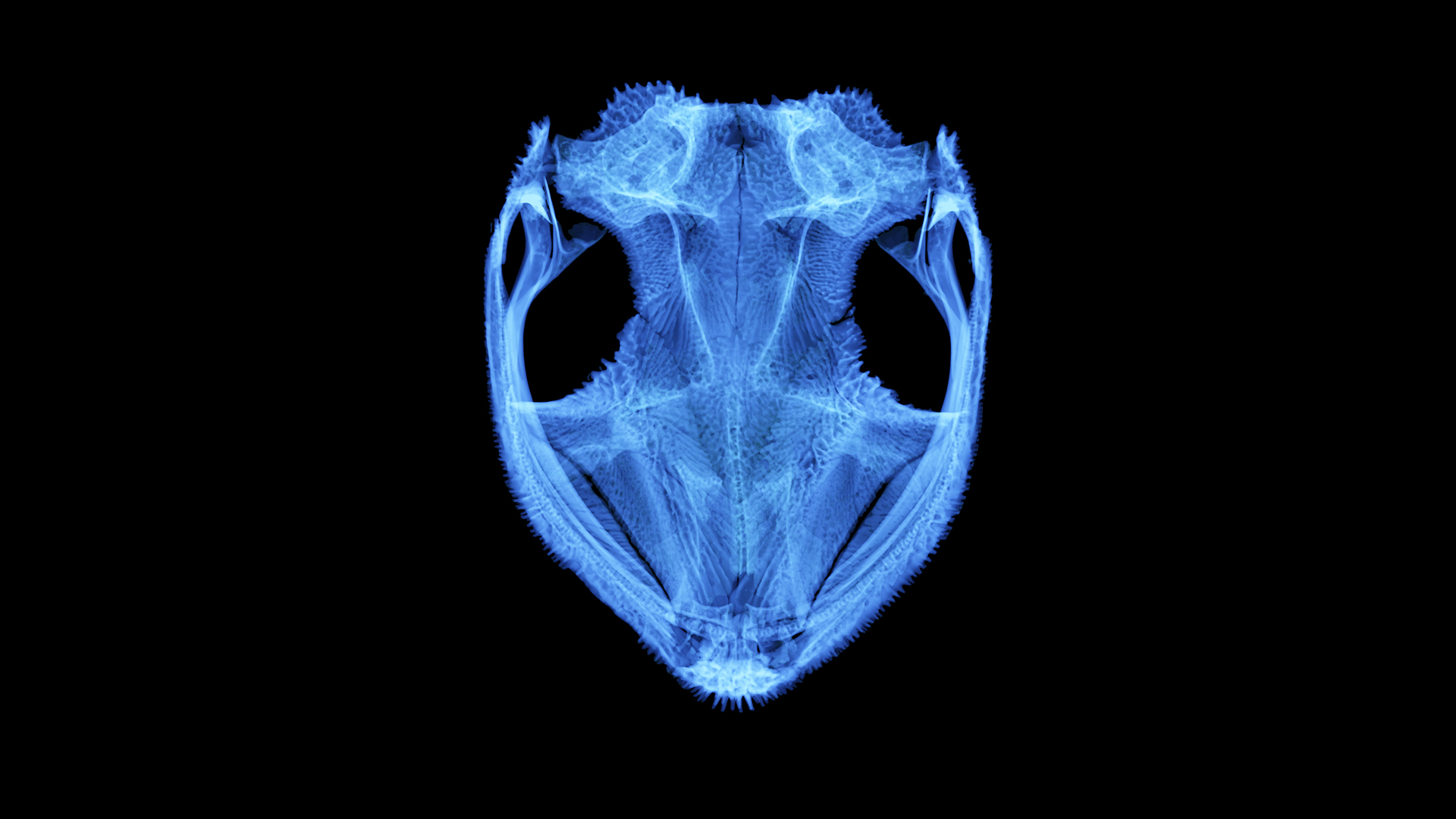

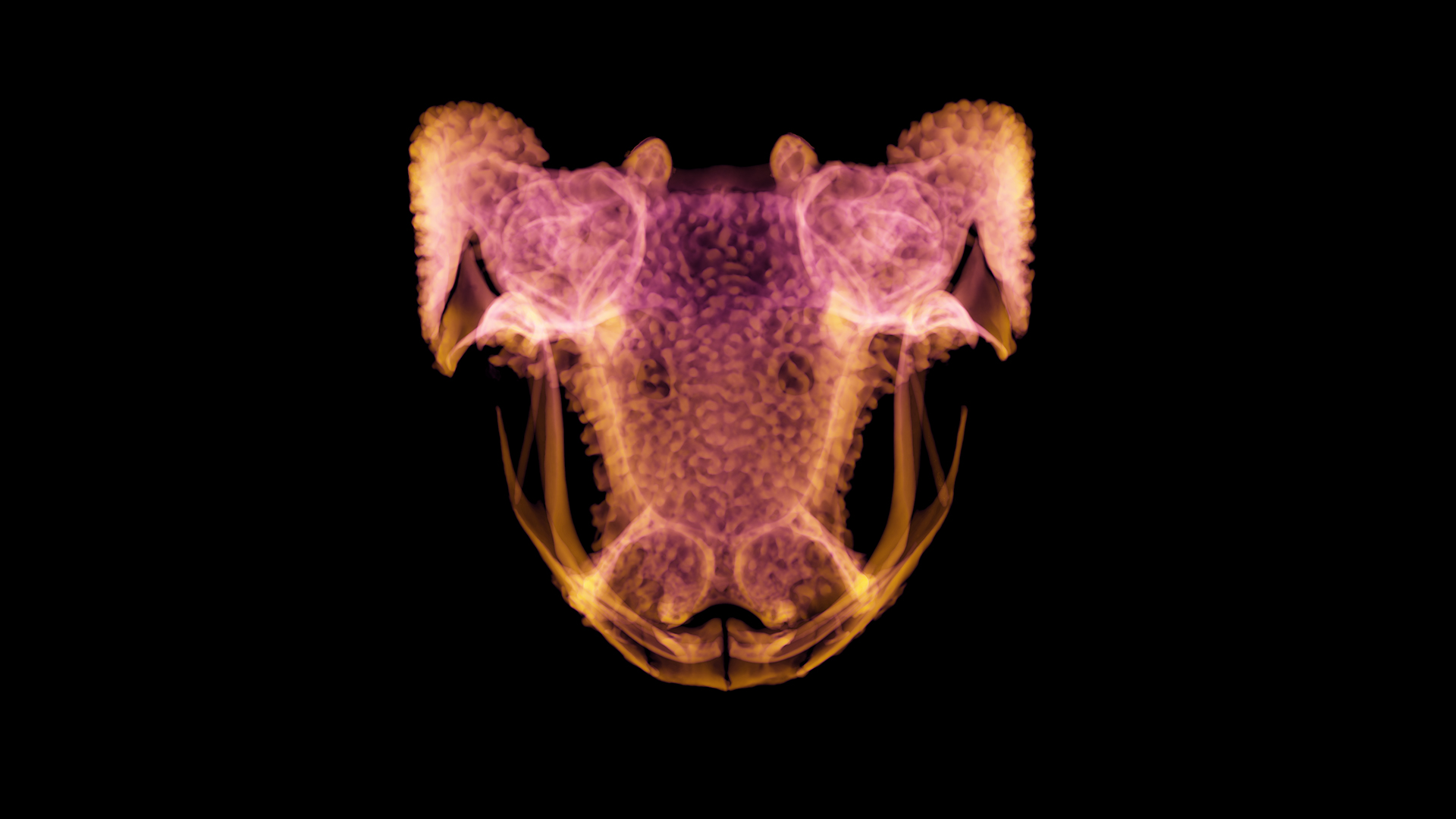

Frogs' heads may look smooth and rounded on their surfaces, but peek under the skin of some species and you'll find skulls that resemble the heads of mythical dragons, studded with spikes, spines and other bony structures.

Scientists recently highlighted the diversity of frog skulls in a series of incredible images, part of a new study investigating skull evolution and function in armored frogs.

In these frogs, skulls can be shield-shaped or exceptionally wide; they may be pocked by grooves or adorned with pointy bits that may provide extra protection against being eaten, the researchers reported.

Related: In photos: Cute and colorful frogs

Artificial color in the images indicates variations in bone density in different skull parts, said lead study author Daniel Paluh, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Biology at the University of Florida. In the image of the horned frog Hemiphractus scutatus, "blue parts of the skull, such as the braincase, are lower density than the green regions, including the jaws," Paluh told Live Science in an email.

There are approximately 7,000 known frog species. For the study, the scientists collected data from 158 species representing all of the major frog families. They found that not only was there a lot of variety in skull shapes; some of those variations appeared across different lineages, separated by millions of years of evolution.

"For example, large, fortified skulls with intricate patterns of pits and grooves have independently evolved in the African bullfrog, South American horned frog and the Solomon Island leaf frog," Paluh said. "And all of these species are ambush predators that will eat other vertebrates."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shovel-headed tree frogs, whose flattened skulls resemble gardening tools, use their heads to block entry to the cracks and holes where they live. Their skulls also have spines, ridges and grooves, "in addition to very wide skull roof bones that provide protection from predators," Paluh explained.

"Because all frogs look so similar, there has been limited interest in studying the evolution of their anatomy," Paluh said. "Our study demonstrates there is still much to learn about the evolution, ecology and anatomy of these amazing animals."

The findings were published online today (March 27) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- So tiny! Miniature frog species are among world's smallest (photos)

- Nature's most bizarre frogs, lizards and salamanders

- 40 freaky frog photos

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus