2,000-year-old flower offerings found under Teotihuacan pyramid in Mexico

The bouquets had survived a bonfire.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

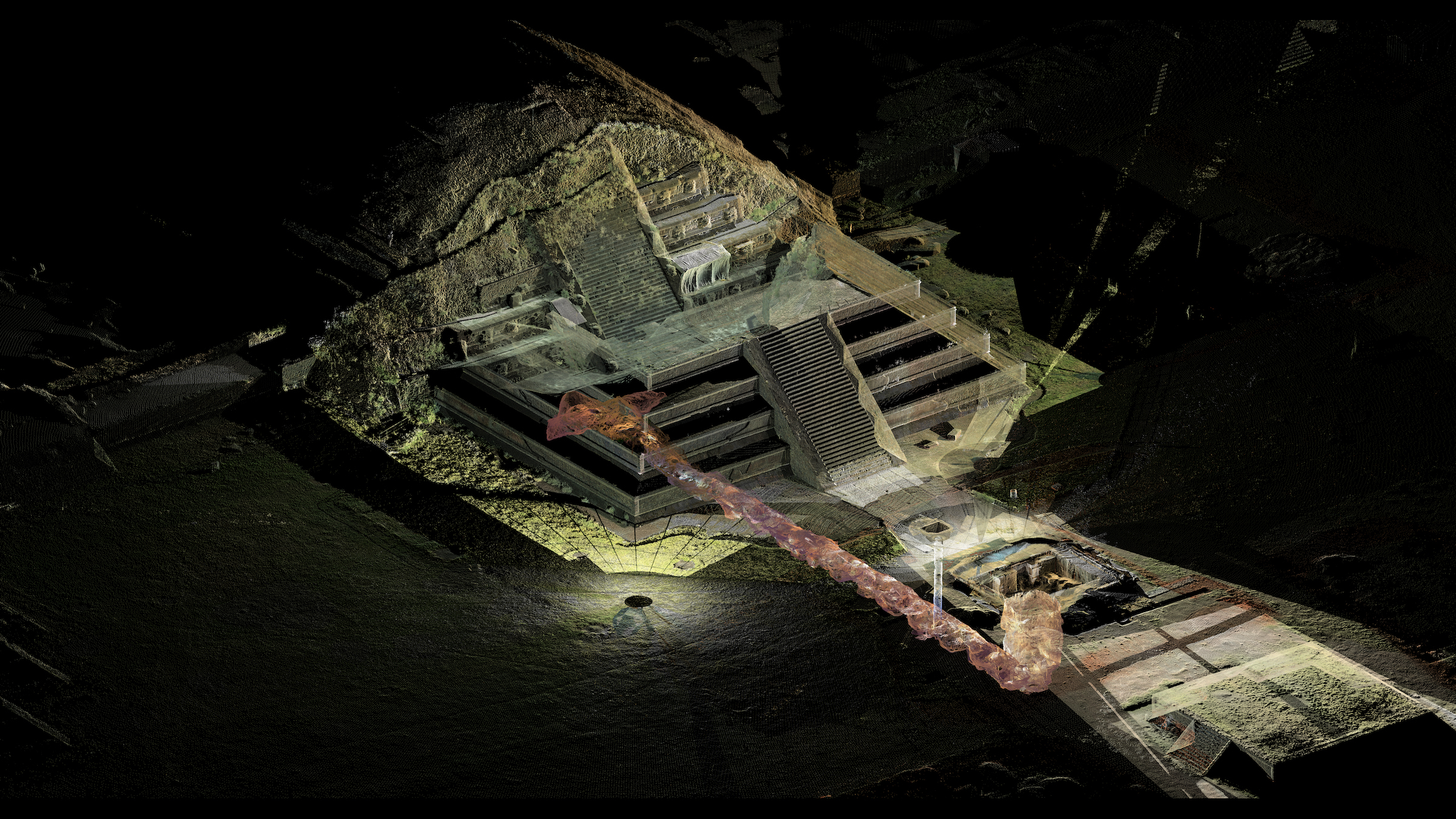

Nearly 2,000 years ago, the ancient people of Teotihuacan wrapped bunches of flowers into beautiful bouquets, laid them beneath a jumble of wood and set the pile ablaze. Now, archaeologists have found the remains of those surprisingly well-preserved flowers in a tunnel snaking beneath a pyramid of the ancient city, located northeast of what is now Mexico City.

The pyramid itself is immense, and would have stood 75 feet (23 meters) tall when it was first built, making it taller than the Sphinx of Giza from ancient Egypt. The Teotihuacan pyramid is part of the "Temple of the Feathered Serpent," which was built in honor of Quetzalcoatl, a serpent god who was worshipped in Mesoamerica.

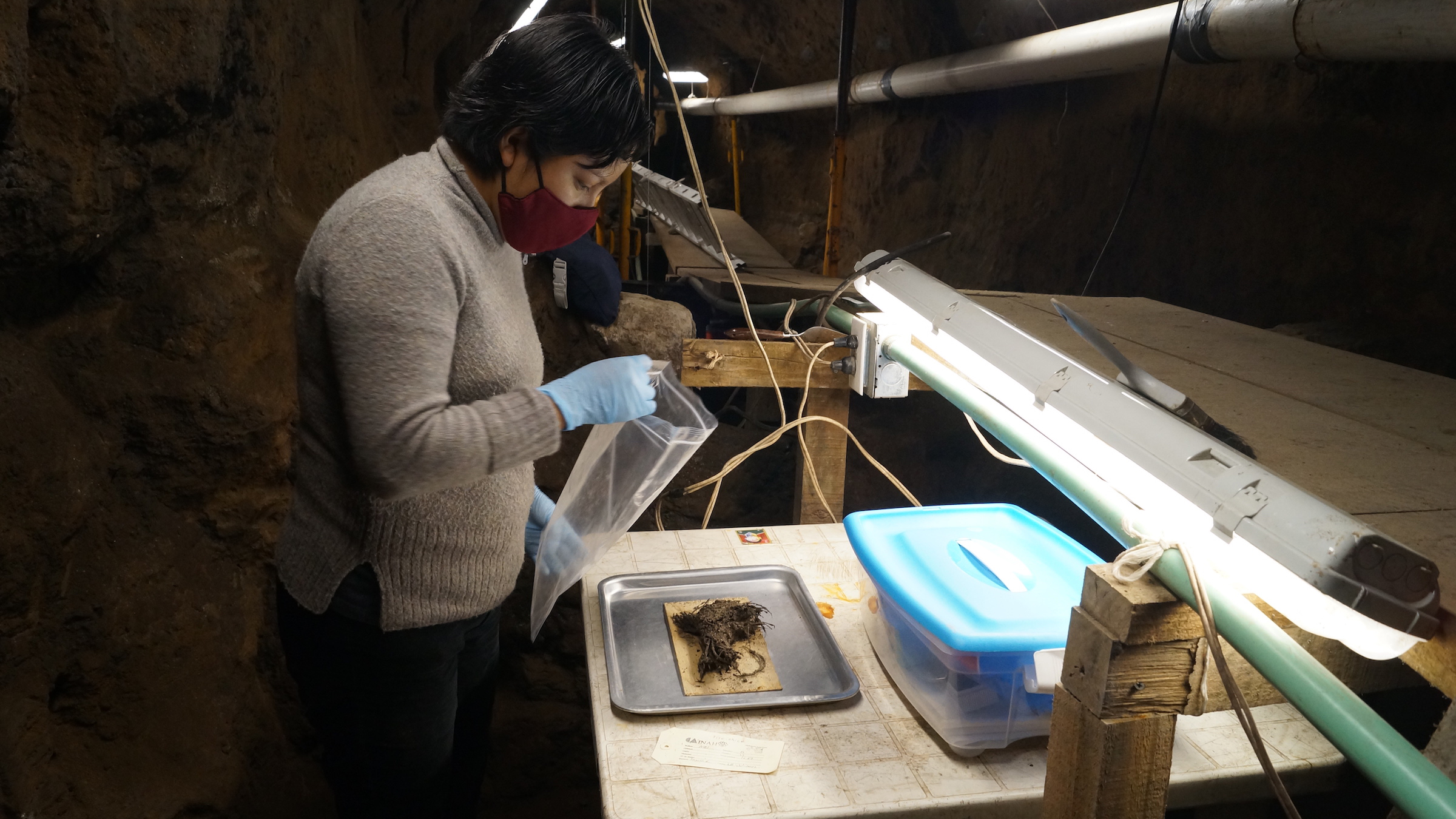

Archaeologists found the bouquets 59 feet (18 m) below ground in the deepest part of the tunnel, said Sergio Gómez-Chávez, an archaeologist with Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) who is leading the excavation of the tunnel. Numerous pieces of pottery, along with a sculpture depicting Tlaloc, a god associated with rainfall and fertility, were found beside the bouquets, he added.

The bouquets were likely part of rituals, possibly associated with fertility, that Indigenous people performed in the tunnel, Gómez-Chávez told Live Science in a translated email. The team hopes that by determining the identity of the flowers, they can learn more about the rituals.

Related: Photos: The amazing pyramids of Teotihuacan

The team discovered the bouquets just a few weeks ago. The number of flowers in each bouquet varies, Gómez-Chávez said, noting that one bouquet has 40 flowers tied together while another has 60 flowers.

Archaeologists found evidence of a large bonfire with numerous pieces of burnt wood where the bouquets were laid down, Gómez-Chávez said. It seems that people placed the bouquets on the ground first and then covered them with a vast amount of wood. The sheer amount of wood seems to have protected the bouquets from the bonfire's flames.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The tunnel that Gómez-Chávez's team is excavating was found in 2003 and has yielded thousands of artifacts including pottery, sculptures, cocoa beans, obsidian, animal remains and even a miniature landscape with pools of liquid mercury. Archaeologists are still trying to understand why ancient people created the tunnel and how they used it.

Teotihuacan contains several pyramids and flourished between roughly 100 B.C. and A.D. 600. It had an urban core that covered 8 square miles (20 square kilometers) and may have had a population of 100,000 people.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus