Rare Flesh-Eating Bacteria Invaded Woman's Eye Sockets

This is a highly unusual place for the life-threatening infection to take hold.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A woman developed an infection with "flesh-eating" bacteria in her eye sockets — a highly unusual place for the life-threatening infection to take hold, according to a new case report.

The 58-year-old woman went to the emergency room after she developed eye pain and swelling that had become progressively worse over five days, according to the report, published Nov. 7 in The Journal of Emergency Medicine.

An eye exam showed she had severe swelling around both her eye sockets as well as pus discharging from her eyes.

Related: 27 Oddest Medical Case Reports

At first, it appeared that she could have cellulitis, a bacterial infection of the skin and underlying tissues.

But when the patient's symptoms worsened even after she received antibiotics, doctors suspected she could have a more serious condition — necrotizing fasciitis, an infection that destroys skin and muscle tissue and spreads quickly in the body.

These "flesh-eating" infections are rare overall, and necrotizing fasciitis of the eye socket is rarer still, with only a handful of cases ever reported in the medical literature, the authors wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A tissue sample taken from the women's eye socket — known medically as the orbit — confirmed that she had orbital necrotizing fasciitis.

Study co-author Dr. Ryan Walsh, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Tennessee, said he had never seen a case like this before. It's "probably a once in a career case," Walsh told Live Science.

Although rare, people can get necrotizing fasciitis when bacteria enter the body through breaks in the skin, including cuts and scrapes, burns and surgical wounds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Necrotizing fasciitis can occur anywhere in the body, but is most commonly seen in the limbs or the abdominal wall, according to the University of Iowa. The rich blood supply in the face and eyes generally helps reduce the risk of flesh-eating infections in these areas, Walsh said. (Flesh-eating infections tend to thrive in low-oxygen environments with reduced blood supply, Walsh added.)

When cases of orbital necrotizing fasciitis do occur, they are most often seen after surgery or trauma in people with conditions that make them more susceptible to infection, such as diabetes. In the current case, it's unclear how the woman acquired the infection, but she was taking a medication for rheumatoid arthritis that weakened her immune system, which increased her risk of severe infections, Walsh said.

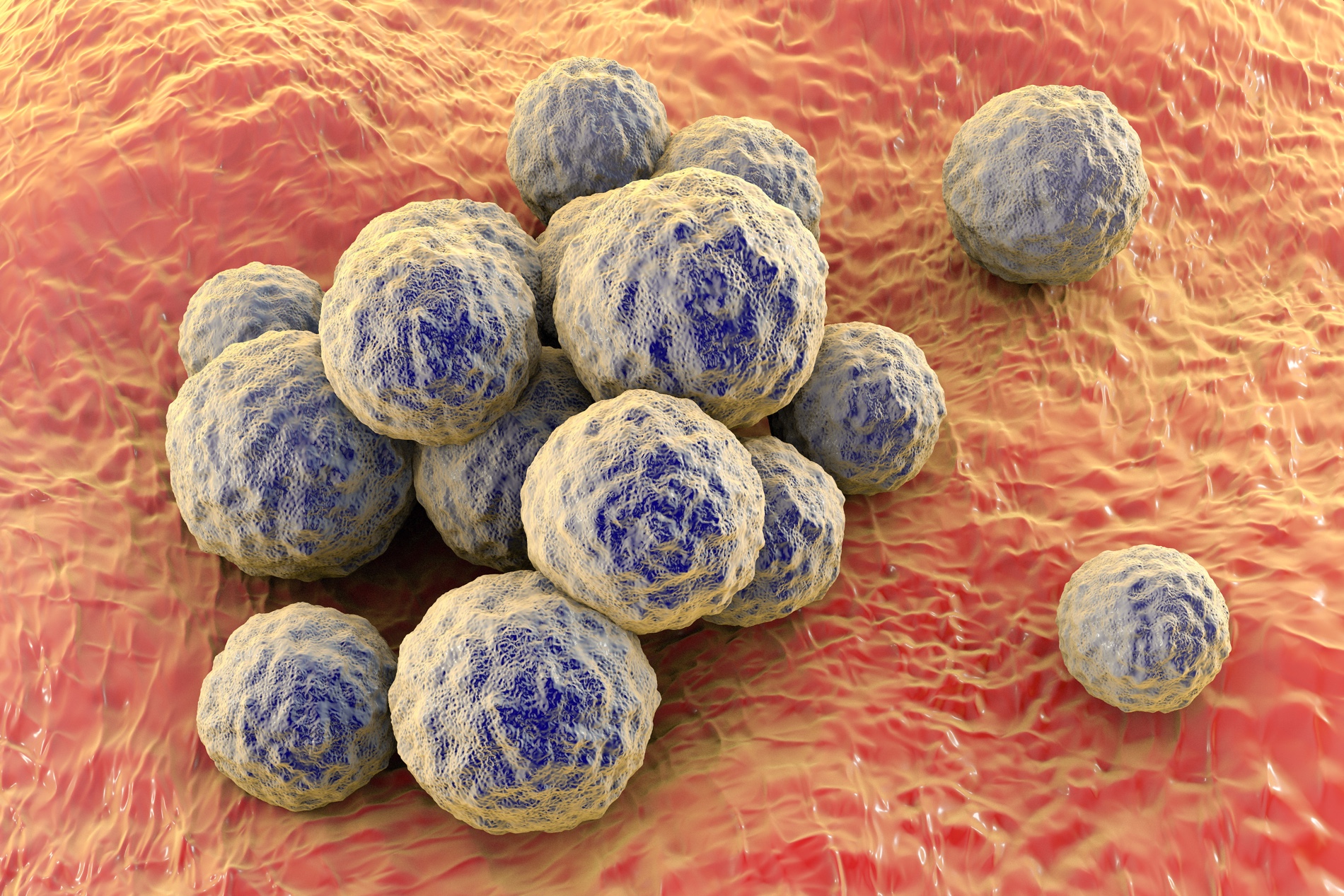

Several types of bacteria can cause necrotizing fasciitis. In the woman's case, tests showed she was infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Streptococcus pyogenes.

But regardless of the cause, the condition is usually very serious, even fatal. Up to one-third of patients with necrotizing fasciitis die from their infection, according to the CDC. The fatality rate from orbital necrotizing fasciitis is about 12%, the authors said.

The woman underwent repeated surgeries to remove damaged or dead tissue from the area, and received antibiotics to treat the specific strains of bacteria she was infected with.

After 13 days in the hospital, she was well enough to go home. She was released in stable condition, Walsh said, and to his knowledge she does not have vision loss.

- 27 Devastating Infectious Diseases

- 10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors

- 6 Superbugs to Watch Out For

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus