Ecuadorian shrunken head used in 1979 movie 'Wise Blood' was real, experts say

A tsantsa, or shrunken head, that was brought to the U.S. in the 1940s has been repatriated.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A shrunken head from Ecuador that was brought to the United States in the 1940s (and in 1979 was loaned as a prop to the film "Wise Blood") has been authenticated and repatriated to its country of origin.

In 1942, James Ostelle Harrison — a faculty member at Mercer University in Atlanta, Georgia, now deceased — acquired the object, known as a "tsantsa," during his travels in Ecuador. Harrison donated the head to the university, where it was displayed in campus museums for decades. Then, in the 1980s, the university placed the tsantsa in storage.

Such tsantsas were crafted from human heads — typically belonging to a slain enemy — and were made and used in rituals in Ecuador until the middle of the 20th century by men in the Amazonian Shuar, Achuar, Awajún/Aguaruna, Wampís/Huambisa and Candoshi-Shampra populations, known collectively as the SAAWC culture groups, according to a new study about the artifact.

In the 19th century, Western and European interest in tsantsas as "keepsakes and curios" created a commercial demand for the objects, according to the study. Some tsantsas that were crafted for export were, indeed, human, but weren't intended for Indigenous rituals, and many of the exported shrunken heads were made from the corpses of animals such as monkeys or sloths, or from synthetic materials. In the study, scientists confirmed that the Mercer tsantsa was not only genuine, but also that it was created specifically for ceremonial use more than 80 years ago, using techniques that were practiced by Indigenous people in the Ecuadorian Amazon, university representatives said in a statement.

Related: Photos: The amazing mummies of Peru and Egypt

In 2018, the completion of a new science facility at Mercer brought the tsantsa to the attention of lead study author Craig Byron, a Mercer biology professor. In preparation for the move into the new building, Byron was overseeing the cataloging and relocation of Georgia bird and mammal taxidermy specimens, which were collected during the middle of the 20th century and were once used for teaching, he told Live Science in an email.

Among those specimens was the tsantsa, which the researchers identified as potential human remains and an important cultural artifact, Byron said. The head measured about 5 inches (12 centimeters) high, and while it was known to have come from Ecuador, there was no documentation verifying its authenticity, as it was collected prior to the establishment of regulations and protocols that now safeguard against trafficking in cultural artifacts and human remains, Byron said in the email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists contacted the Ecuadorian Embassy, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and the National Cultural Heritage Institute; they agreed to authenticate the artifact and produce a report for the Ecuador's National Cultural Heritage Institute (Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural, INPC), to determine if the tsantsa should be repatriated.

Creating a traditional tsantsa begins with the removal of the head from a dead adversary's body, "as close to the shoulders as possible," the researchers wrote in the study, published May 11 in the journal Heritage Science. Skin layers are stripped from the skull, and then molded back into a 3D "head" shape, preserved through stages of soaking, simmering, dry heating with hot sand and "ironing" with hot stones, followed by smoking. The eyes and lips and a seam at the back of the new, smaller head are stitched together with plant fibers.

By the end of this process, the head is "no larger than a clenched adult human fist," according to the study. Heads that are ritually prepared in this way were thought to retain the abilities of a slain enemy; these powers could then be transferred in a ceremony to the household of the head's new owner, the scientists reported.

Preserving the past

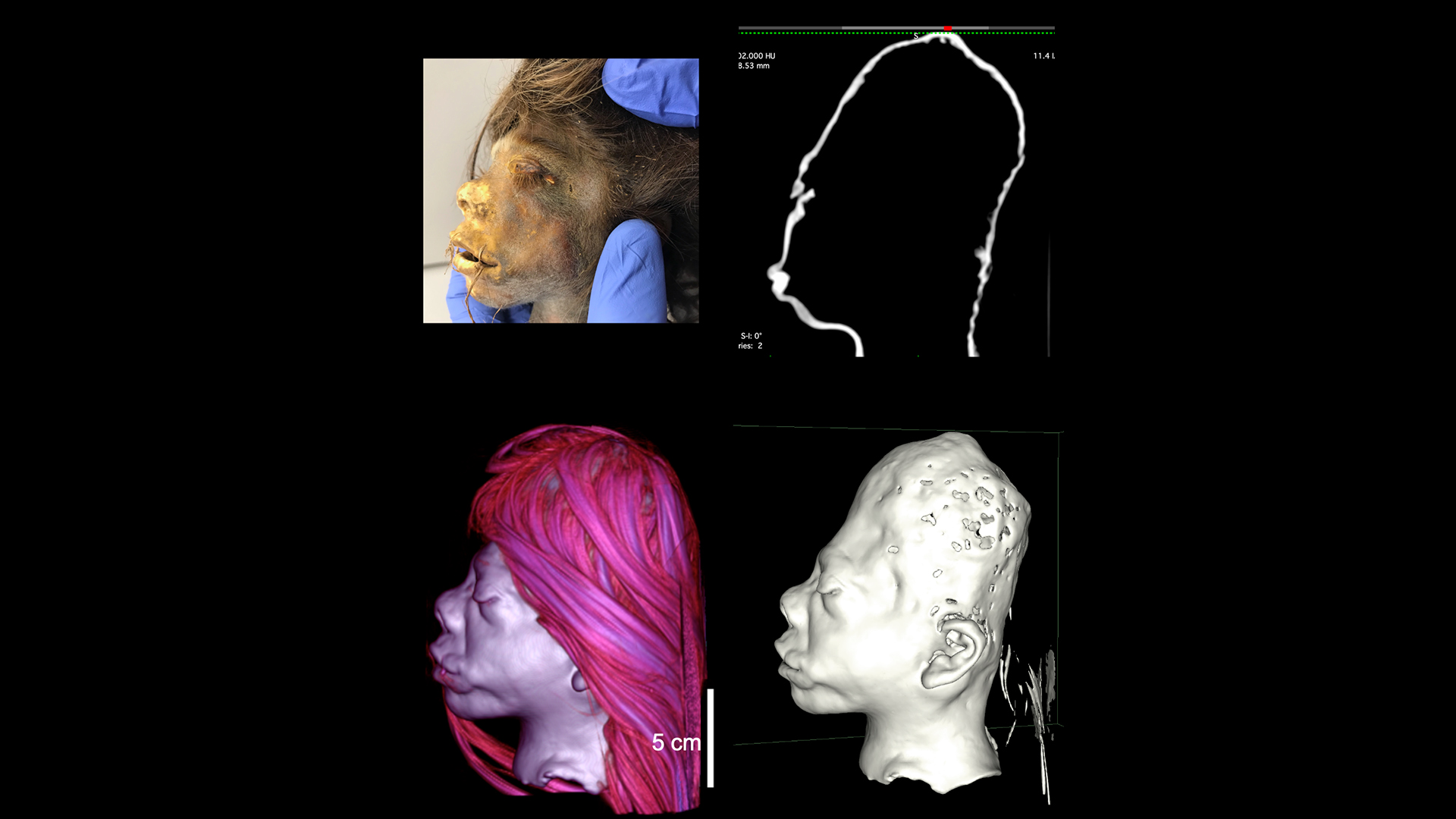

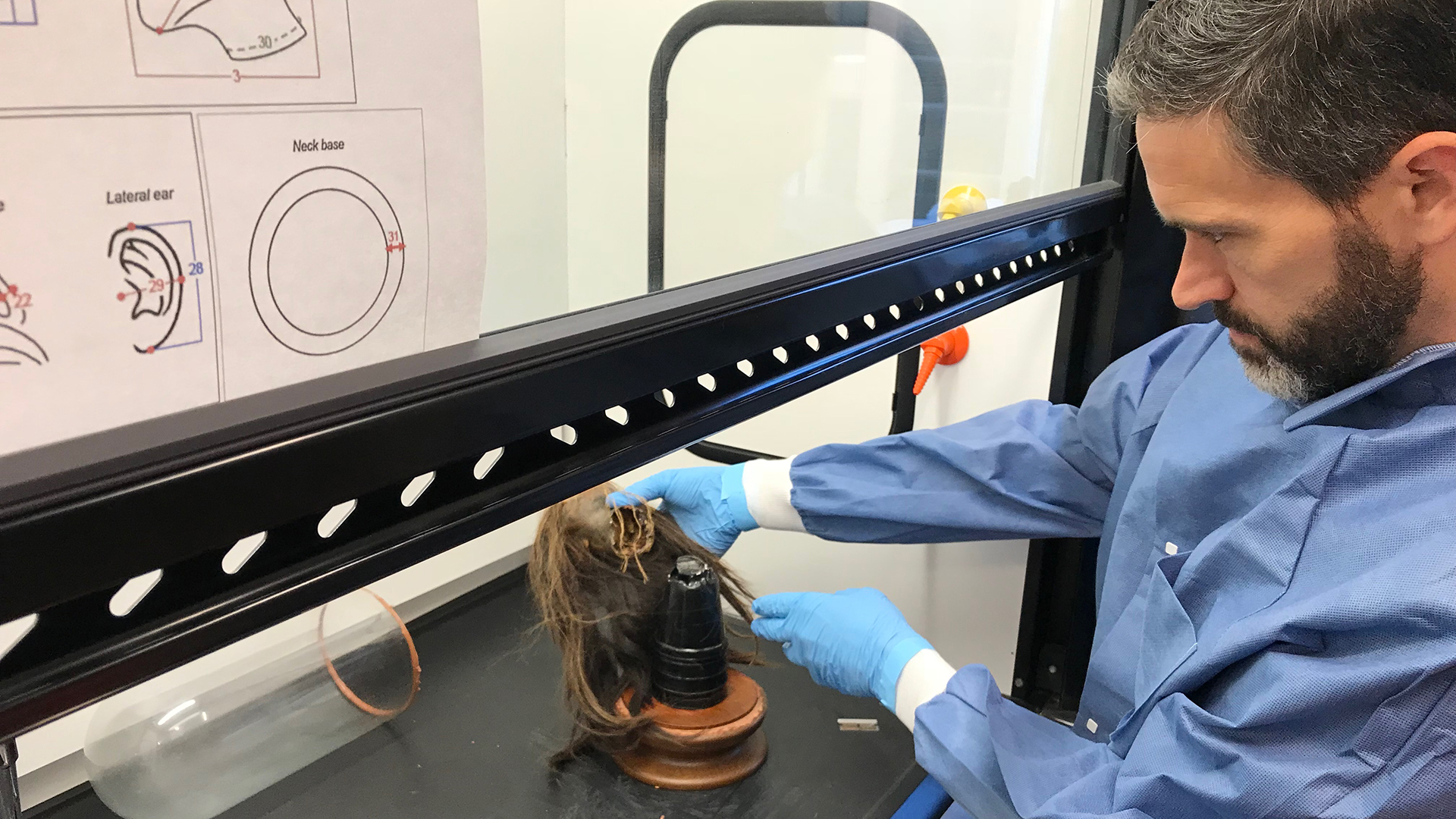

In February 2019, the scientists scanned the head using computed X-ray tomography (CT) and built 3D digital models — with and without hair. To verify that the Mercer tsantsa was both human and ceremonial, the researchers consulted a checklist of 33 criteria from prior studies of these objects. The list described features such as the color, density and texture of the skin; the structure of facial features and anatomy; and signs of traditional fabrication, including stitching style, charcoal traces in the head cavity, and a hole in the top of the head for attaching a cord.

Morphology of the ears, mouth and nose, as well as human head lice eggs in the hair, confirmed that the tsantsa was human. Attributes such as the mouth-stitching technique, overall skin texture and a hole at the top — a detail only visible on the CT scans, and something that is usually absent in synthetic or commercial tsantsas — showed that the tsantsa was made traditionally by hand and not commercially produced, Byron said. There were also visible marks in the skin made by the hands that shaped the head, he added.

"You can even see where fingers and thumbs would have been used to hold and 'work' the skin during the shrinking process," he said. "Also, the skin had the polishing we expected [in a traditionally prepared head] by studying other observations in the peer-reviewed science literature."

The head met 30 of the 33 criteria for authenticity, and was repatriated to the General Consulate of Ecuador in Atlanta, Georgia, on June 12, 2019, according to the study. Objects like the tsantsa represent the world's diminishing cultural diversity, which "is rapidly shrinking with each passing month," Byron said.

Repatriating cultural objects and human remains to their countries of origin — and collaborating with those nations to do so — will be an important part of preserving this legacy, and is an opportunity for cultural institutions to address the presence of objects in their collections that were acquired through colonialism, the study authors wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus