Photos: Snapshots of mysterious Sutton Hoo burial excavation revealed

Mercie Lack and Barbara Wagstaff were at Sutton Hoo in 1939 to capture the dramatic discovery on camera.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When an Anglo-Saxon ship burial was unearthed at Sutton Hoo in summer 1939, two photographers were on hand to record the thrilling excavations. Now, after 80 years, their unique images have been digitized and published online.

Sutton Hoo, in east England, contains 18 burial mounds, dating to around the seventh century A.D. Most of the mounds were looted by treasure-seekers centuries ago, but in 1939, archaeologists excavated the largest mound and found an undisturbed burial site containing the remnants of an 89-foot-long (27 meters) ship, as well as a sword, armor and objects crafted from gold, garnet and silver. The finds revealed a wealth of information on Anglo-Saxon culture and burial rituals, and they are considered among the most famous archaeological discoveries ever made in the United Kingdom.

Two photographers, Mercie Lack and Barbara Wagstaff, shot over 400 images, as well as short videos of the excavation, between Aug. 8 and 25, 1939. By documenting the discovery, they made a "truly significant contribution to the photographic and archaeological record, while also capturing the social history of an excavation taking place on the eve of the Second World War," the National Trust, a heritage-conservation organization that now owns Sutton Hoo, wrote on its website.

Related: Massive Anglo-Saxon cemetery and treasure unearthed in England

Lack's great-nephew Andrew recently donated a set of Lack's photographs to the National Trust, which has conserved, cataloged and digitized the images to help preserve them for the future and share the photographers' unique view of the excavations at Sutton Hoo. "Mercie Lack and Barbara Wagstaff helped capture some of these precious moments in time and their photographs can now be enjoyed for generations to come," the National Trust representatives wrote after the photos were posted online in September 2021.

Here, Live Science shares some of these newly digitized images from the iconic dig.

Barbara Wagstaff and Mercie Lack

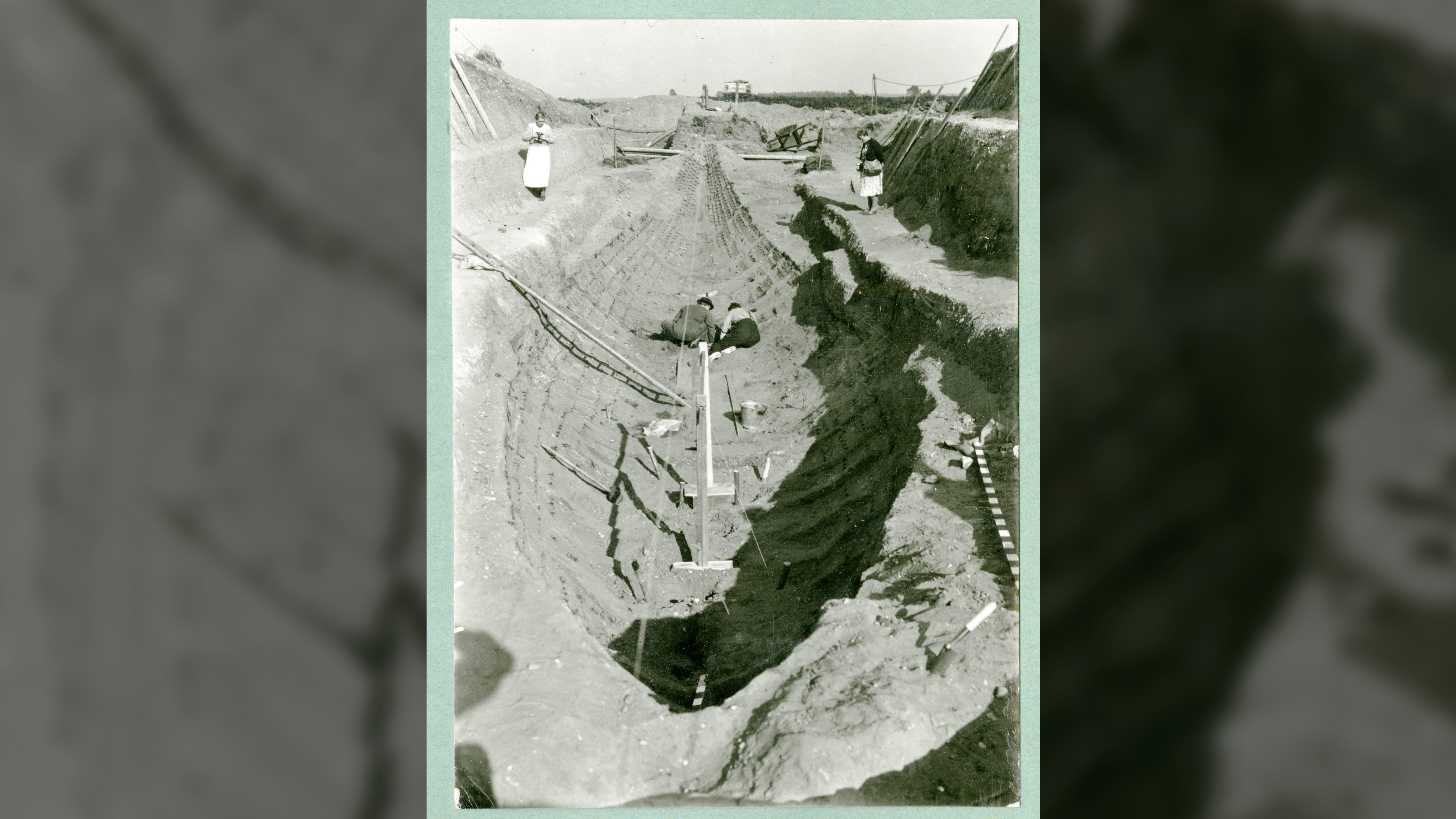

Barbara Wagstaff (right) and Mercie Lack (left) stand on each side of the ship as they document the excavations. The two amateur photographers hoped that their images would help capture this unique moment in history. "It is hoped, that, by means of the photographic records taken on the site at the time, some idea of the process of uncovering the boat may be conveyed to later generations who cannot have the chance of seeing it emerge from its sandy grave," Lack said (as quoted by the British Museum).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Excavation prints

Lack shows members of the excavation team a selection of contact prints. Lack and Wagstaff were teachers and friends, as well as keen amateur photographers with an interest in archaeology. According to The Guardian, Lack was on holiday in the area at the time of the excavation when the story was first reported. She quickly obtained permission to document the work, and also got clearance for Wagstaff to join. Lack later used the images she captured to become an associate of the Royal Photographic Society, the British Museum noted.

Related: The most amazing coin treasures uncovered in 2021

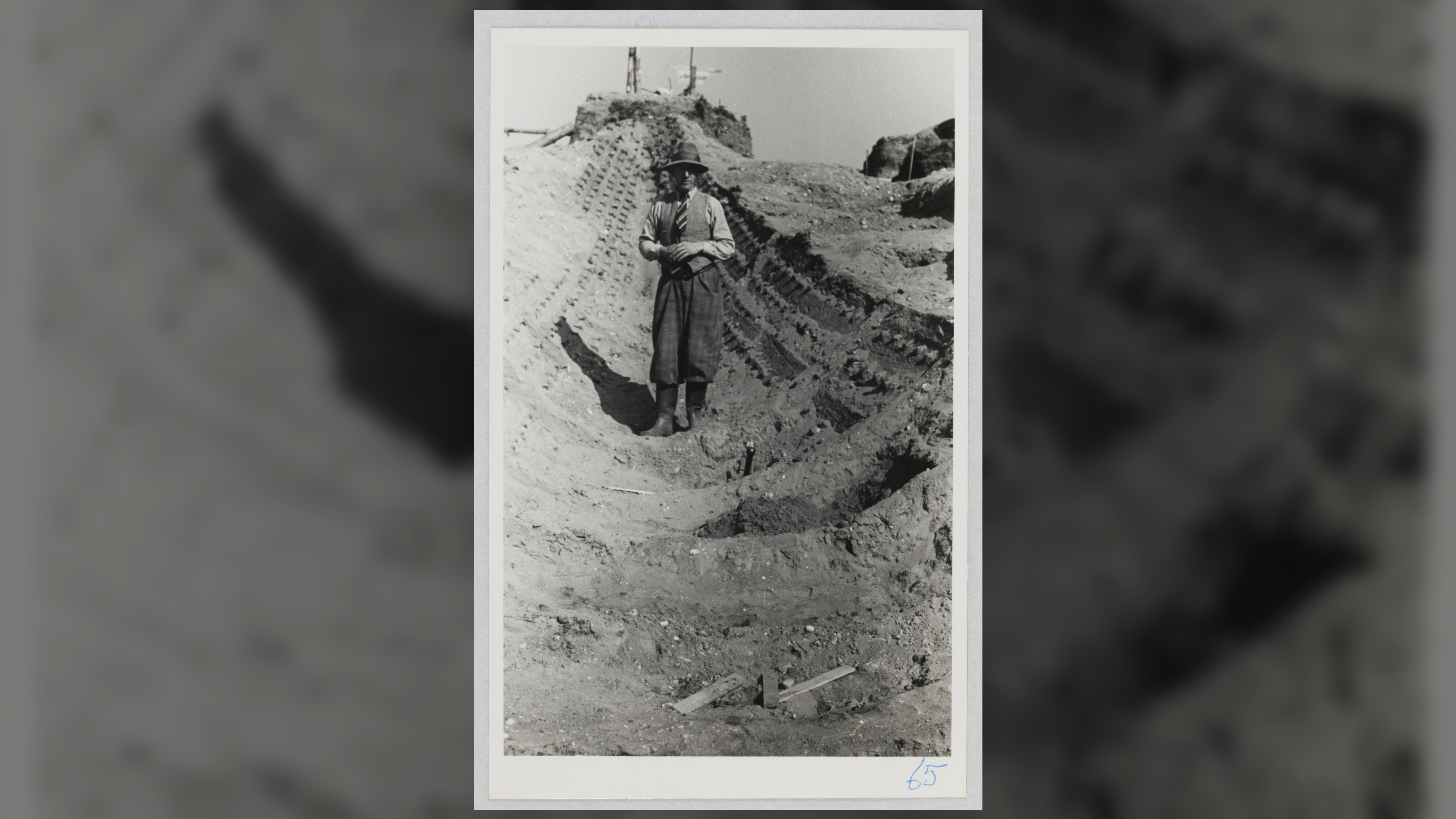

Basil Brown

Basil Brown, shown here, was a local archaeologist who was hired by Edith Pretty, the owner of Sutton Hoo, to excavate the mounds. He cycled 35 miles (56 kilometers) each way between Sutton Hoo and his home to excavate the site, according to the BBC. Brown worked for Ipswich Museum in England at the time and continued working as an archaeologist until 1965, the BBC reported.

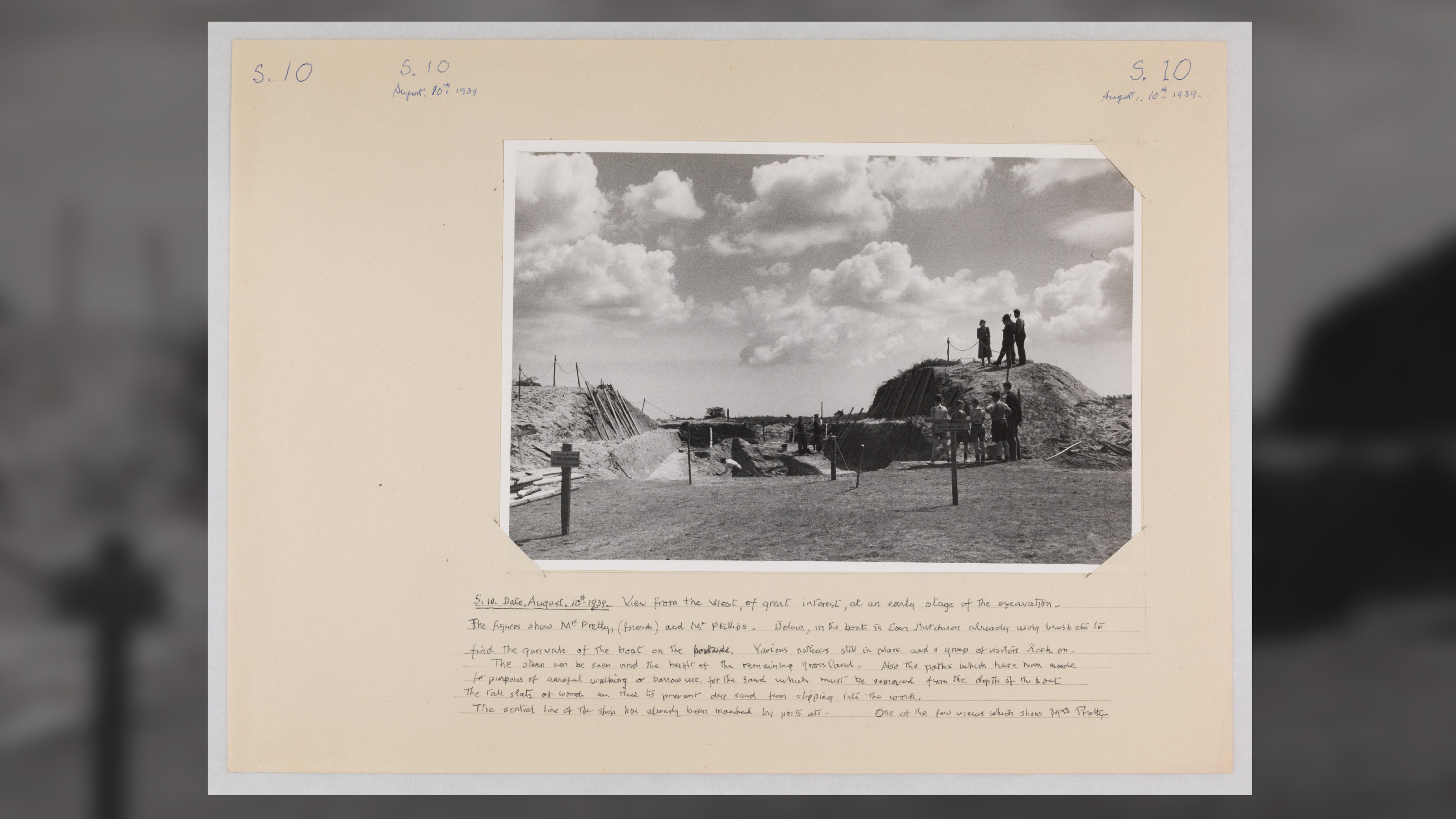

Edith Pretty

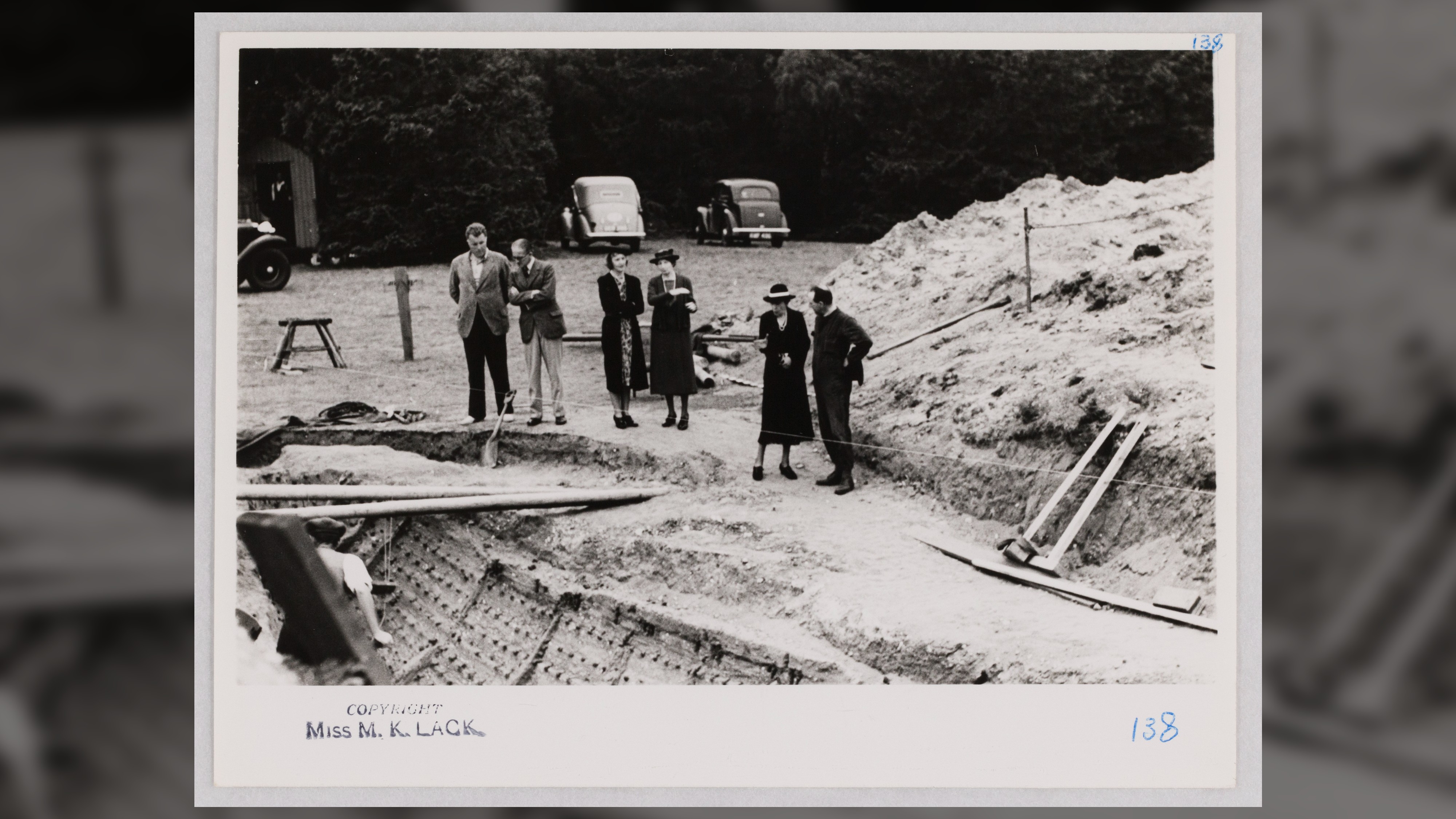

Pretty, archaeologist Charles Phillips and others stand on top of the burial mound and watch the excavations on Aug. 10, 1939. Pretty had a keen interest in archaeology. According to the British Museum, "She travelled extensively throughout her youth, visiting Pompeii, the Egyptian pyramids, tombs and monuments at Luxor, and other significant digs with her father, who himself excavated a Cistercian abbey adjoining their home at Vale Royal [a former borough in England]." Pretty moved into the Sutton Hoo estate in 1926 and funded the dig herself starting in 1938. She "oversaw the excavations herself for two years, and when the largest mound unearthed what looked like a huge ship burial, she knew it was of enormous historic significance," British Museum representatives wrote.

Following the unprecedented discoveries, Pretty was declared the rightful owner of the finds by a jury at a coroner's inquest into the treasure trove, but she donated all of the artifacts to the British Museum.

Related: Photos: Roman-era silver jewelry and coins discovered in Scotland

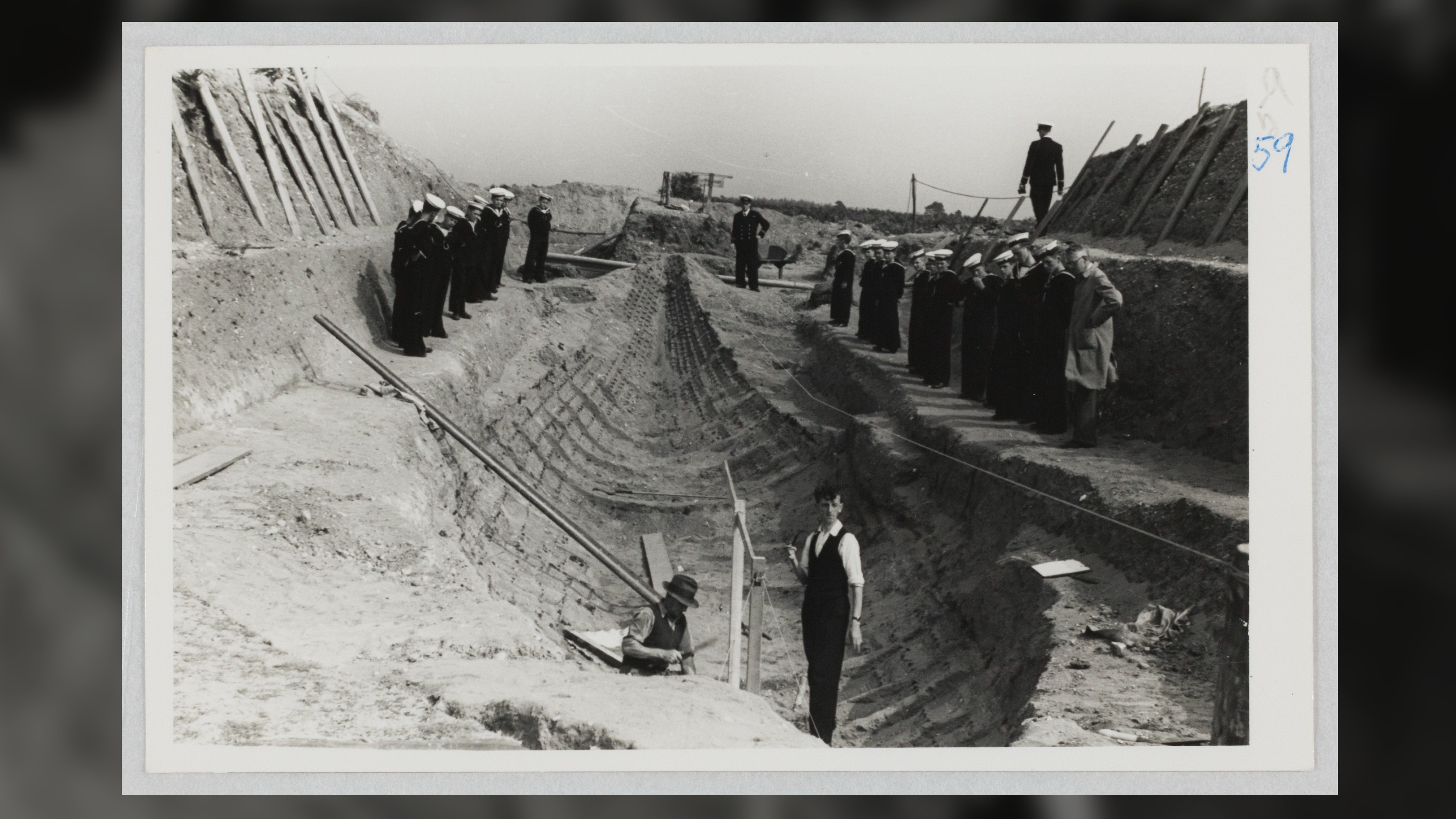

Naval cadets

In this image, a group of visiting naval cadets views the excavations. The dig generated a huge amount of excitement in Britain at the time, and visitors came to watch the excavation unfold. The discoveries were initially kept under wraps to avoid public attention. "I hope … the newspapers won't get hold of anything concerning the find before an announcement is made later on," Brown wrote in his diary on June 6, 1939 (as quoted by Mark Mitchells on the Sutton Hoo Ship's Company website). But the excavations finally came to light in July. The East Anglian Daily Times, which broke the story, compared the finds to the discovery of Tutankhamun: "[The discovery could be] as important in this country as the finding of the tomb of Tutankhamen to Egypt," the newspaper reported in July 1939, according to an East Anglian Daily Times article from 2019.

Royal visit

Princess Marie Louise (second from right), granddaughter of Queen Victoria, visited the site on Aug. 22, 1939, and was photographed with Phillips (left), Pretty (third from right) and Lt. Cmdr. J.K.D. Hutchison (right).

Related: 30 of the world's most valuable treasures that are still missing

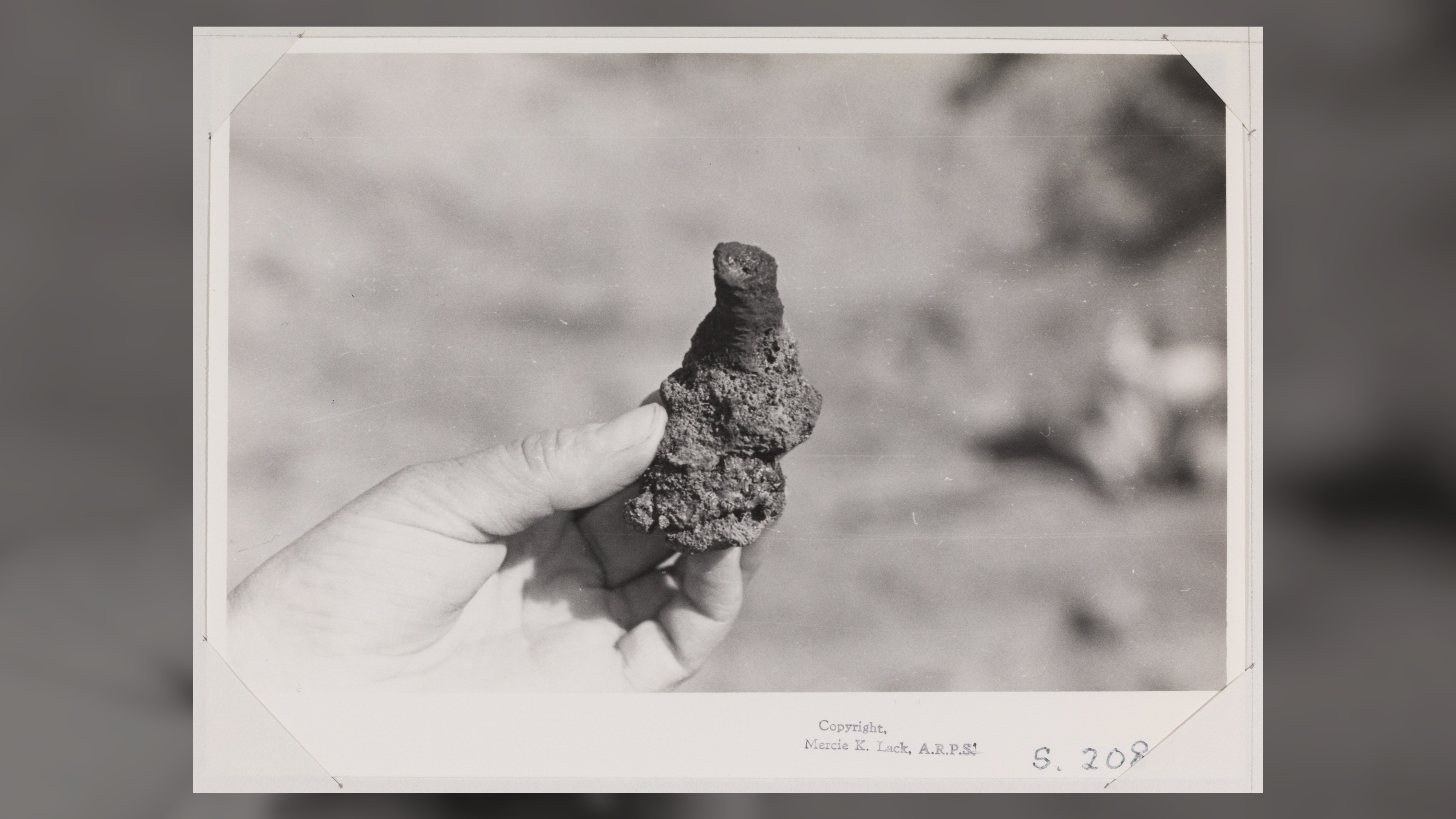

Ship's rivet

Wagstaff holds a corroded ship's rivet from the excavation. The ship, made of oak, had rotted away in the acidic soil, leaving a "ghost" imprint behind, but the iron rivets survived. Archaeologists don't know for certain who was buried with the ship, although some speculate that it held Raedwald, a seventh-century king of East Anglia. Ship burials are rare in England and were likely reserved for people of very high status, due to the effort and human power needed to create the burials, including dragging a ship from a river, digging a trench, building a chamber to house the body and then erecting a mound over it all, according to the British Museum.

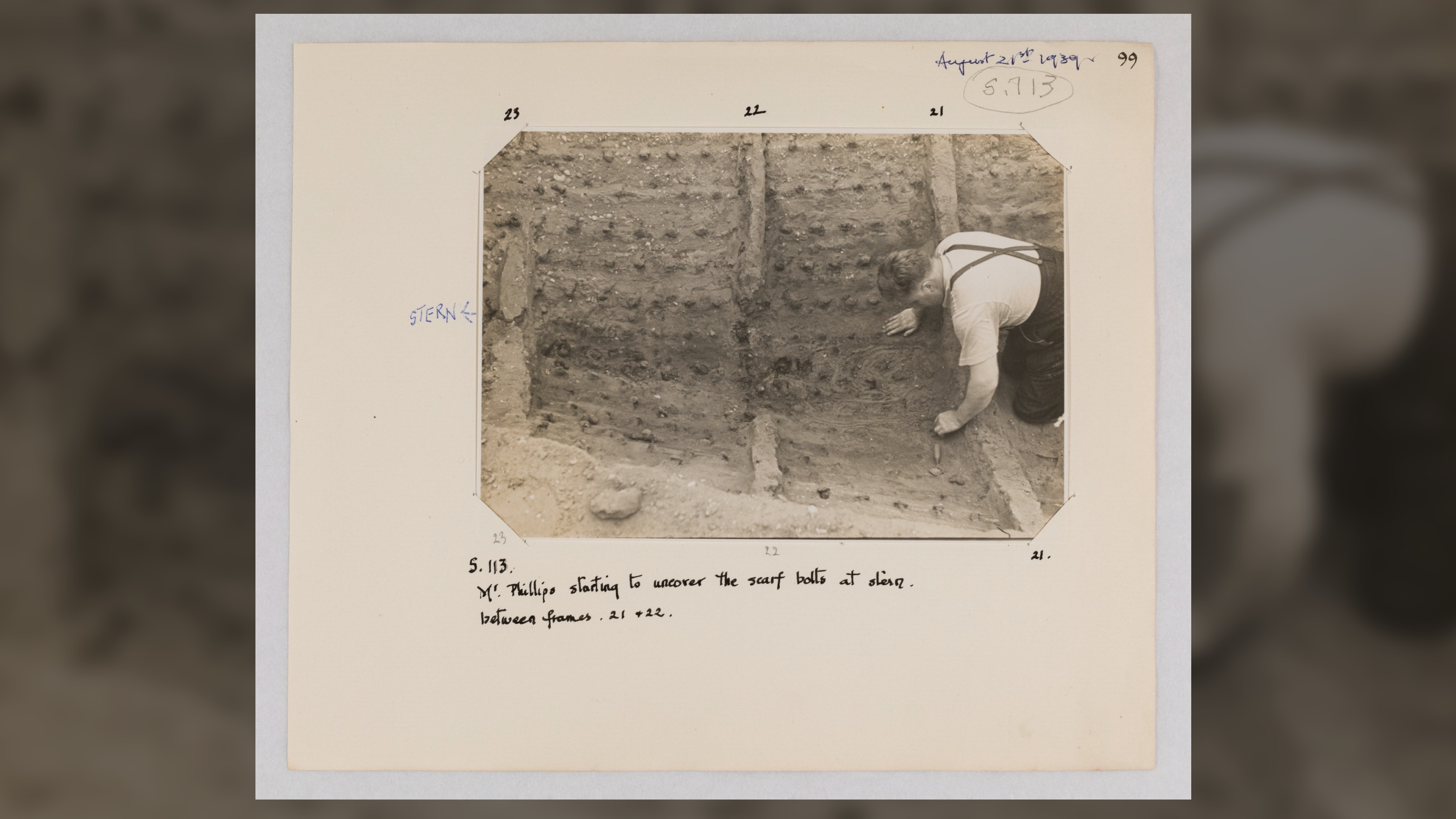

Charles Phillips

Phillips uncovers the scarf bolts at the stern of the ship between frames on Aug. 21 and 22, 1939. Phillips, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, took over the excavations from Brown once it became clear that the finds were of international importance.

Related: 24 amazing archaeological discoveries

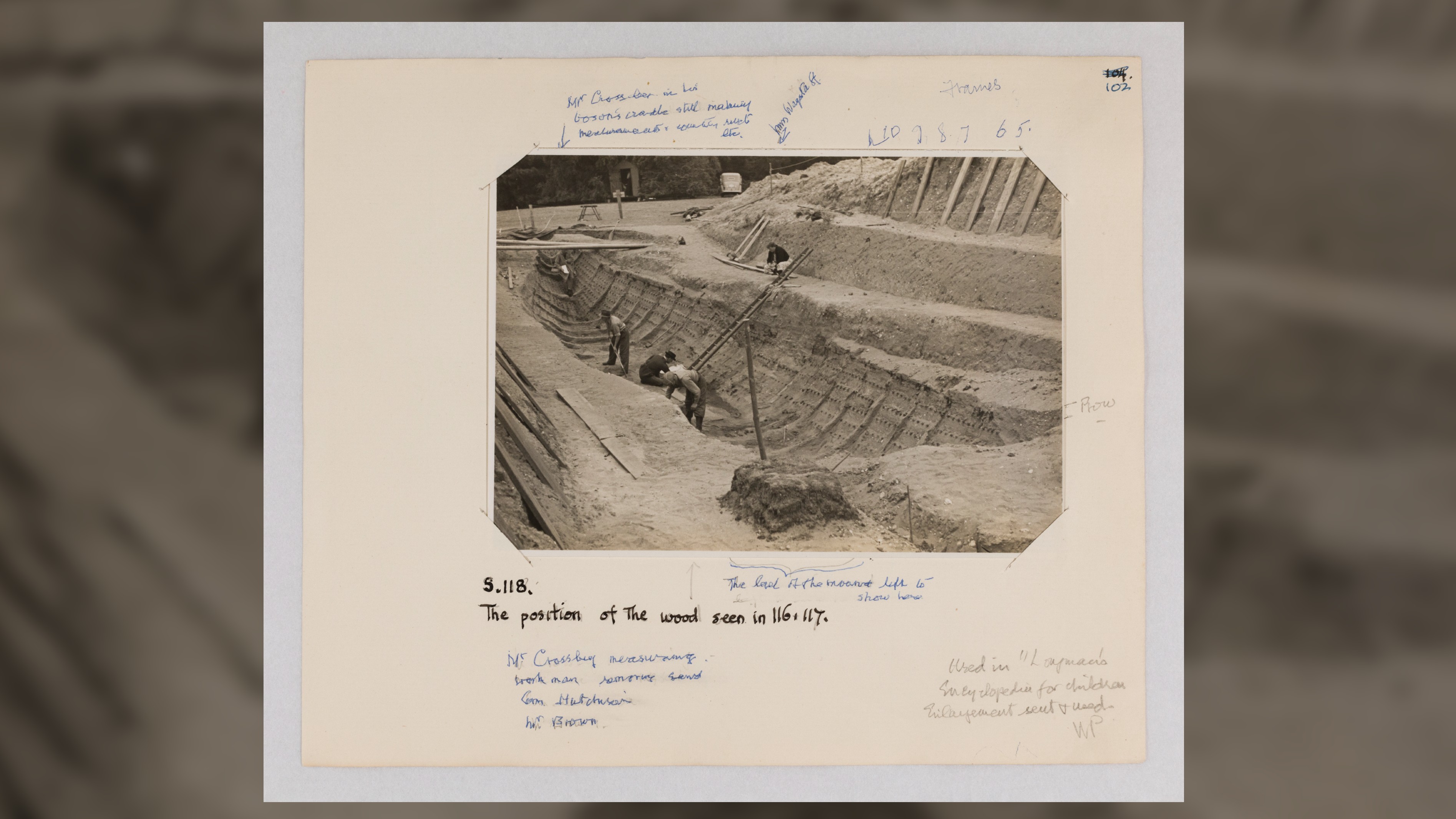

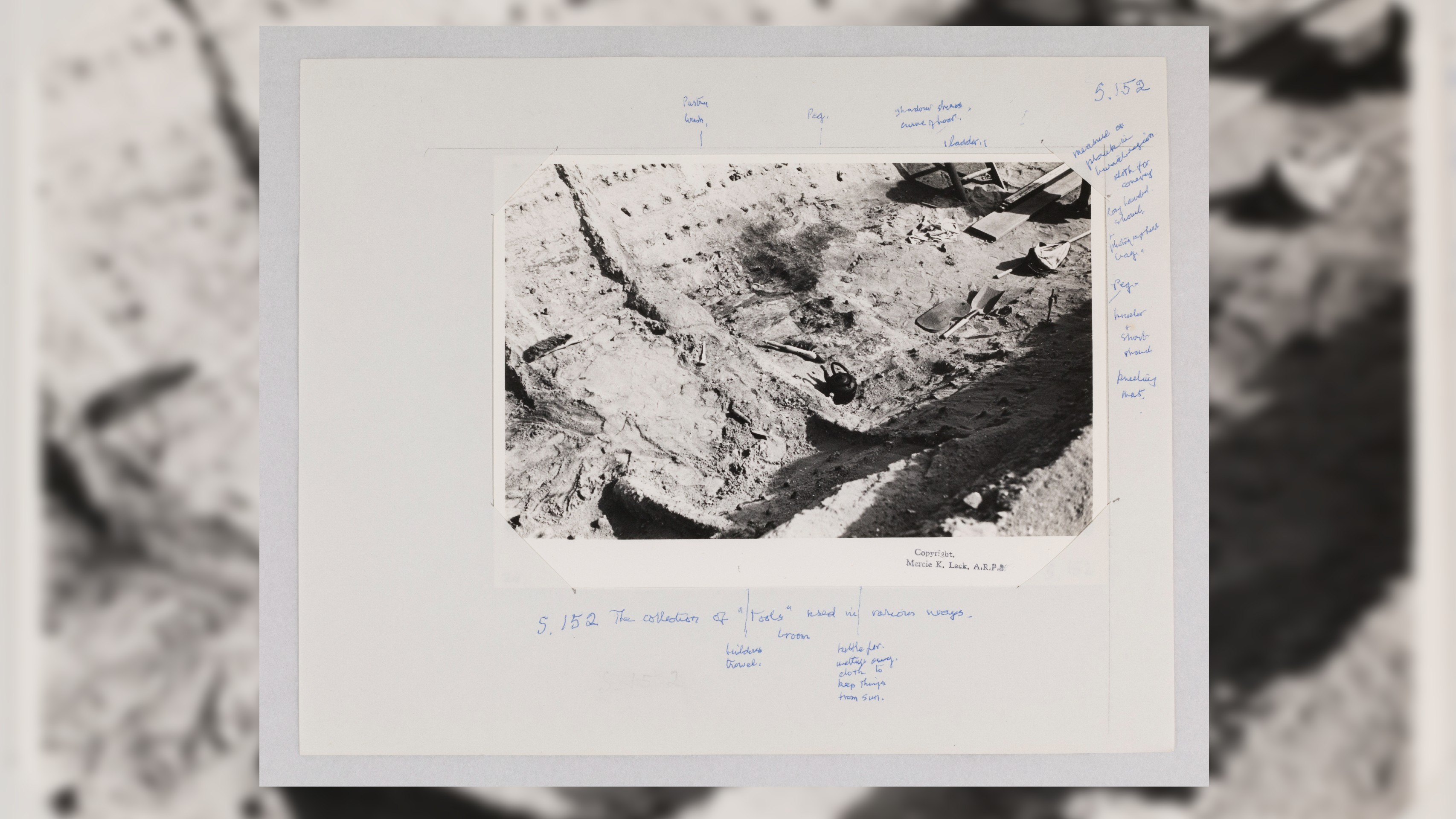

Meticulous annotations

This shot by Lack shows the ongoing excavations, with Wagstaff observing. Lack "meticulously annotated" many of her images and began to draft an unfinished book on the excavations, according to the National Trust. Work is ongoing to carefully transcribe these annotations and preserve Lack's unique take on the excavations. Lack also often noted technical aspects of her photography, according to the National Trust, "providing an invaluable additional layer of detail to each photograph."

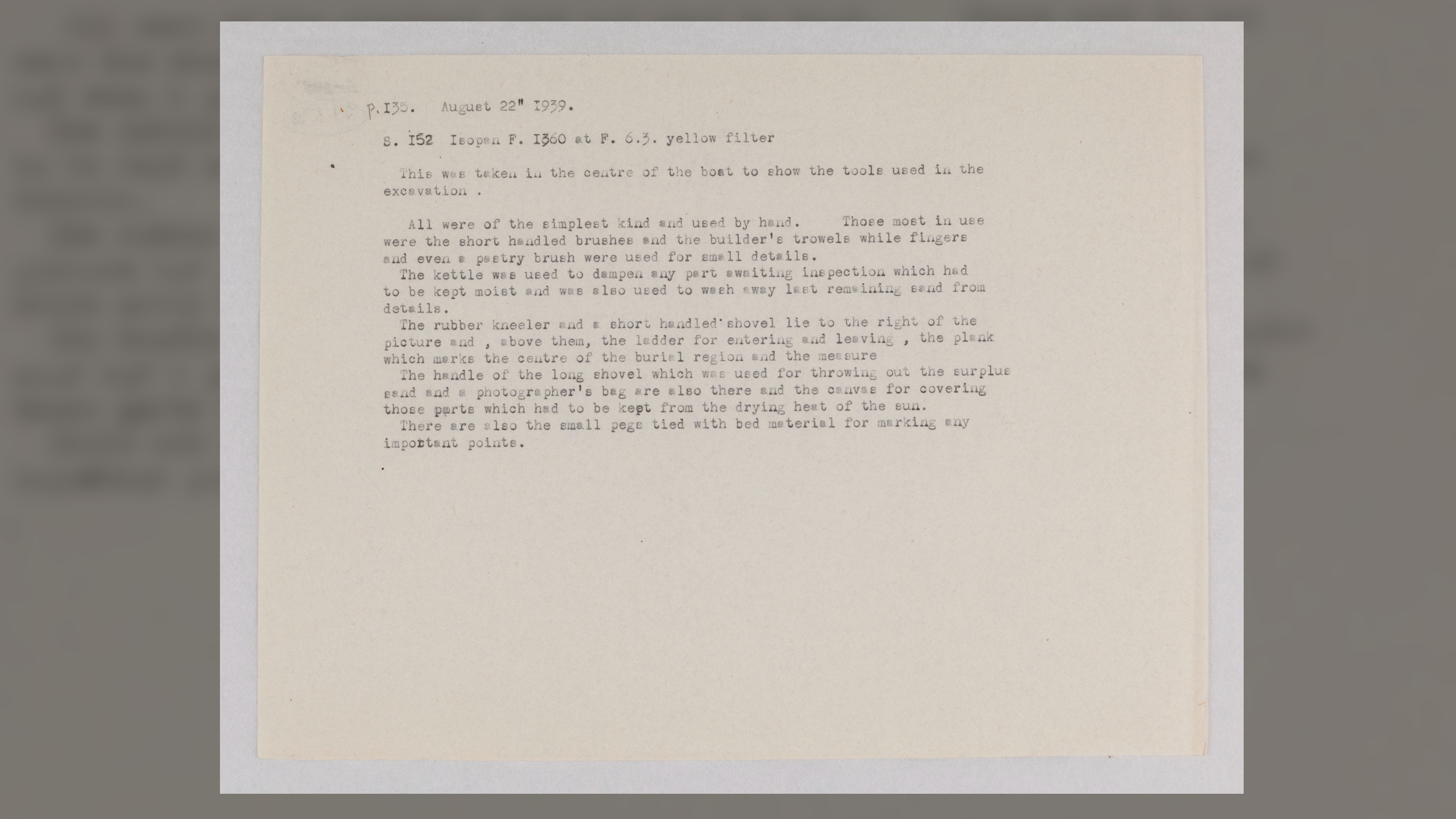

Tools of the trade

Lack wrote detailed notes to accompany this photo, taken during the excavations, and gave extra insight into how the excavations were carried out. "This was taken in the centre of the boat to show the tools used in the excavation," Lack wrote. "All were of the simplest kind and used by hand. Those most in use were the short handled brushes and the builder's trowels while fingers and even a pastry brush were used for small details."

Related: Best free museums in London and the UK

Excavating the mound

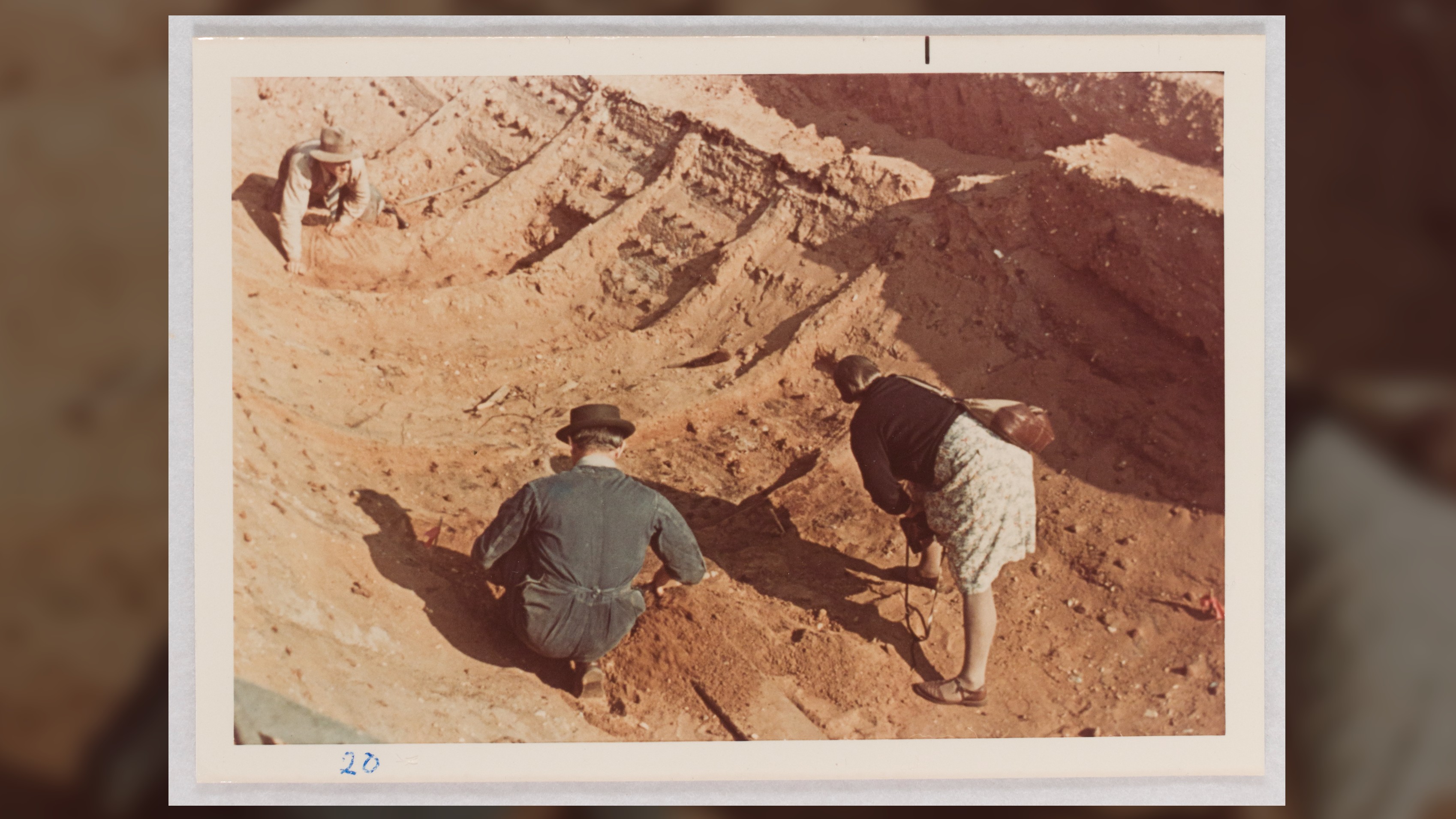

An annotated page from Lack's color album shows a photograph of Brown (top left), Hutchison (bottom left) and Wagstaff (bottom right) at work. Hutchison was a reserve officer in the Royal Navy who conducted a survey of the Anglo-Saxon ship, but his survey was cut short as World War II approached. The site was closed on Aug. 25, 1939, and Britain declared war on Germany on Sept. 3, two days after Germany invaded Poland, according to the Imperial War Museum in London.

Originally published on Live Science.

James is Live Science’s production editor and is based near London in the U.K. Before joining Live Science, he worked on a number of magazines, including How It Works, History of War and Digital Photographer. He also previously worked in Madrid, Spain, helping to create history and science textbooks and learning resources for schools. He has a bachelor’s degree in English and History from Coventry University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus