Climate 'points of no return' may be much closer than we thought

The "tipping points" are also more numerous than researchers previously realized.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

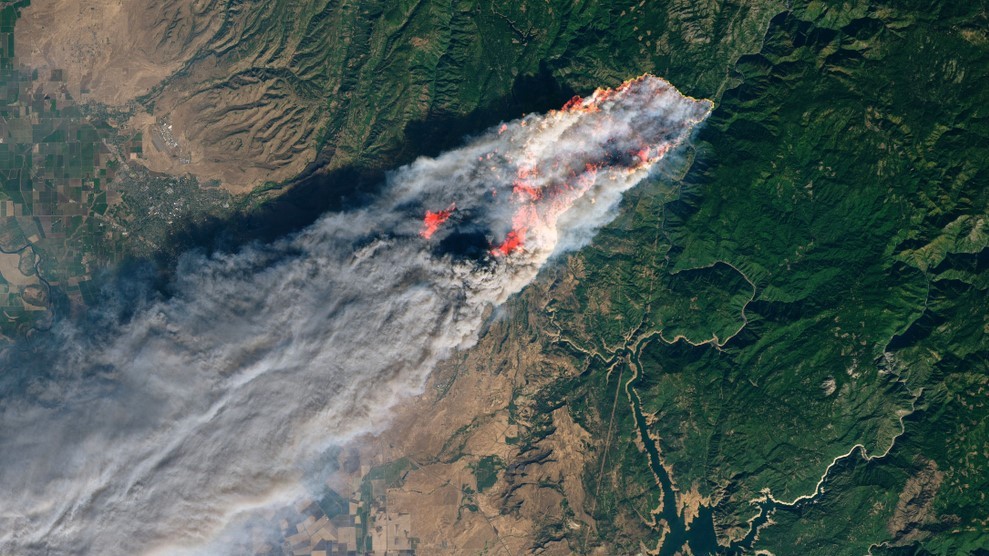

Climate tipping points — the "points of no return" past which key components of Earth's climate will begin to irreversibly break down — could be triggered by much lower temperatures than scientists previously thought, with some tipping points potentially already reached. There are also many more potential tipping points than scientists previously identified, according to a new study.

In climatology, a tipping point is defined as a rise in global temperature past which a localized climate system, or "tipping element" — such as the Amazon rainforest or the Greenland ice sheet — starts to irreversibly decline. Once a tipping point has been reached, that tipping element will experience runaway effects that essentially doom it forever, even if global temperatures retreat below the tipping point.

The idea of climate tipping points first emerged in a 2008 paper published in the journal PNAS, when researchers identified nine key tipping elements that could reach such a threshold due to human-caused climate change. In the new study, which was published Sept. 9 in the journal Science, a team of researchers reassessed data from more than 200 papers on the subject of tipping points published since 2008. They found that there are now 16 major tipping points, almost all of which could reach the point of no return if global warming continues beyond 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) above preindustrial levels.

Earth has already warmed by more than 2 degrees F (1.1 C) above preindustrial levels and, if current warming trends continue, is on track to reach between 3.6 and 5.4 F (2 and 3 C) above preindustrial levels, the study authors said in a statement.

"This sets Earth on course to cross multiple dangerous tipping points that will be disastrous for people across the world," study co-author Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, said in the statement.

Related: Is climate change making the weather worse?

When the researchers conducted their reassessment, they eliminated two of the original nine tipping points due to insufficient evidence — but then, they identified nine new ones that had been previously overlooked, bringing the toal to 16, they reported in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Since I first assessed climate tipping points in 2008, the list has grown and our assessment of the risk they pose has increased dramatically," co-author Tim Lenton, director of the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter in the U.K. and lead author of the original 2008 tipping points paper, said in the statement.

In the new study, the researchers calculated the exact temperature at which each tipping element would be likely to pass its point of no return. Their analysis revealed that five tipping elements — the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets; Arctic permafrost; tropical coral reefs; and a key ocean current in the Labrador Sea — are in the "danger zone," meaning they are quickly approaching their tipping points.

Two of these danger zone tipping points, the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, are already beyond their lowest potential tipping points of 1.4 F (0.8 C) and 1.8 F (1 C) above preindustrial times respectively, which suggests these two systems may already be beyond saving, researchers wrote.

The other 11 tipping points are listed as "likely" or "possible" if warming continues past 2.7 F.

Past estimates, such as the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Sixth Assessment Report, published in three parts in 2021 and 2022, suggested that most major tipping points would be reached only if Earth warmed past 3.6 F, which would give humanity more time to prepare mitigation and adaptation strategies. But according to the new study, those tipping points may be closer than expected.

One explanation for this accelerated timeline is that researchers now fully understand the interconnectedness of tipping points. Better climate models now show that the fall of one tipping point could increase the likelihood of another's collapse. For example, if the Arctic permafrost melts due to rising temperatures, it will release more carbon into the atmosphere. This will further increase surface temperatures on land and in the oceans, thereby accelerating melt in major ice sheets and stressing coral reefs. In other words, tipping points are stacked up like dominoes; as soon as one falls, the others could swiftly follow.

Related: Could climate change make humans go extinct?

Therefore, it is imperative to drastically reduce our greenhouse gas emissions immediately before this irreversible chain reaction begins, the researchers warned.

"To maintain liveable conditions on Earth, protect people from rising extremes, and enable stable societies, we must do everything possible to prevent crossing tipping points," Rockström said. "Every tenth of a degree counts."

But this will be no easy task. To have just a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 2.7 F, greenhouse gas emissions would have to be cut in half by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, the researchers said in the statement.

Given the meager progress in combating climate change, this goal may seem unachievable. In fact, in some ways, we seem to be moving backward; in June, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling severely limited the federal government's ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

However, the study authors argue that it could still be possible to achieve such drastic changes through a different type of tipping point: a social one. This is a theoretical threshold in public opinion that, once passed, will force governments and large corporations to take drastic climate action, the scientists said in the statement.

The only problem is that this social tipping point must be reached well before the climate tipping points are passed — otherwise, it will be too little, too late.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus