8 ominous climate milestones reached in 2021

Signs of accelerating global warming abounded this year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Wildfires. Heat waves. Life-threatening floods. The disastrous consequences of burning fossil fuels and pumping greenhouse gases into Earth's atmosphere are everywhere around us. Study after study directly links human-caused climate change to more powerful and wetter storms, longer and more intense droughts and rising sea levels that threaten coastal communities worldwide.

And 2021 made the accelerating pace of climate change painfully clear.

While we still have time to mitigate the worst climate change impacts, that can happen only if we drastically and quickly reduce greenhouse gas emissions — and soon. Here are eight signs in 2021 that the window to avoid climate catastrophe is closing (though it's still not too late to change course).

Paris Agreement warming targets surpassed

When world leaders signed the climate action pledge known as the Paris Agreement in 2015, they committed to long-term and short-term plans for reducing consumption of fossil fuels and the production of greenhouse gasses linked to climate change. Their goal: restricting global warming to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius). But global average temperatures have already climbed to about 1.8 F (1 C) warmer than they were during pre-industrial times, and the 2015 goal is already out of reach. And the warmer Earth gets, the more warming accelerates; as the planet loses ice and snow, it reflects less heat back into space and absorbs it instead, scientists reported in January in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Read more: We've already blown past the warming targets set by the Paris climate agreement, study finds

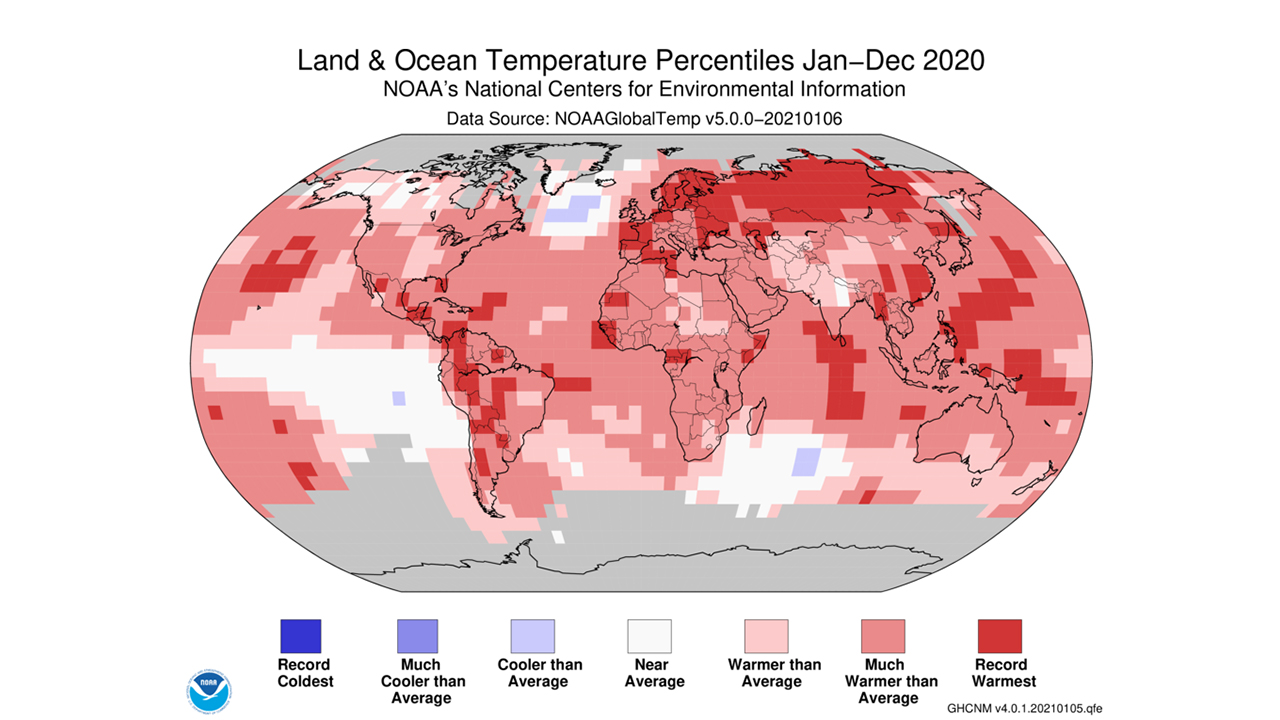

Record-breaking heat in 2020

At the start of 2021, NASA climate scientists announced that 2020 ranked alongside 2016 as the hottest year of all time. Researchers at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York stated in January that 2020's global average surface temperatures were warmer than the 20th-century average by 1.84 F (1.02 C). However, in a separate assessment, researchers with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that 2020 was the second-hottest year after 2016, with temperatures that were 1.76 F (0.98 C) higher than average — just 0.04 F (0.02 C) cooler than 2016's average temperatures. Though the conclusions of the two agencies presented slight variations, both concurred that the current warming trend on Earth is unprecedented, with average global temperatures on the rise for more than 50 years.

Read more: Broiling 2020 was the hottest year ever, NASA climate scientists say

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Faster sea level rise

We've likely been underestimating how quickly sea level rise could happen, a February study showed. Prior models estimated that by the year 2100, global sea-level average would likely rise by 3.61 feet (1.10 meters), but scientists now suggest that oceans will rise even more rapidly than that, based on sea level rise events in Earth's distant past. By evaluating historical data and looking at how quickly seas rose and fell as ancient Earth warmed and cooled, researchers could then estimate a rate for future sea-level rise that was unexplored in previous computations. The scientists found that existing sea-level models predicted more conservative maximums than the new models did, according to the study published in the journal Ocean Science.

Read more: Seas will likely rise even faster than worst-case scenarios predicted by climate models

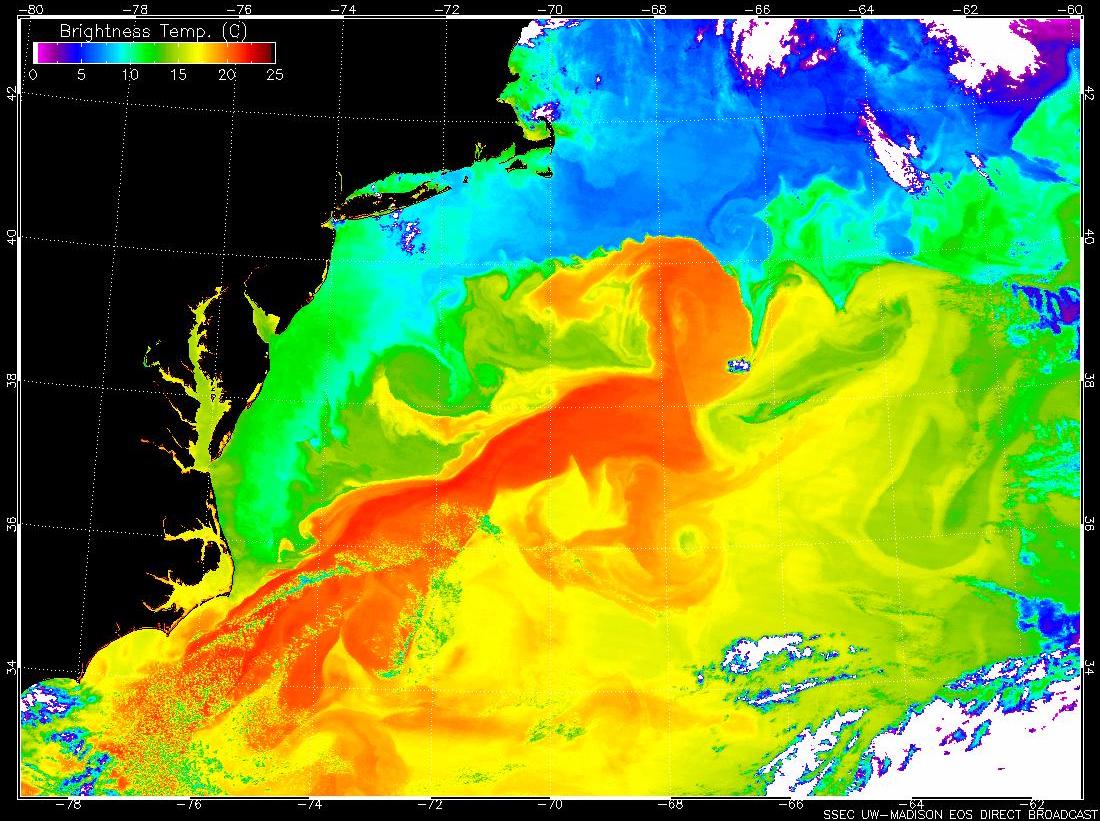

Gulf Stream slowdown

Earth's climate is regulated by ocean currents and one of the most important of these is the Gulf Stream, which acts like a giant conveyer belt transporting heat around the ocean. However, due to human-induced climate change, the Gulf Stream has slowed dramatically and could stop completely by 2100, if global warming continues at its current pace, new research found. The Gulf Stream regulates climate and weather by circulating warm, salty water around the planet. But as Earth warms, melting freshwater ice pours into the ocean, lowering the salinity of the water and disrupting the current's flow. Should the Gulf Stream falter and fail, it could trigger more extreme weather, such as cyclones and heatwaves, and may accelerate sea level rise in coastal Europe and North America.

Read more: The Gulf Stream is slowing to a 'tipping point' and could disappear

Human influence 'unequivocal'

The evidence that humans are driving climate change is crystal clear, according to a report authored by over 200 climate experts who reviewed more than 14,000 studies. In August, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body focusing on climate science, released the first installment of the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report, which stated that human-driven changes are affecting all of Earth's planetary systems in ways that are "widespread and rapid." Hundreds of researchers co-authored the report, finding that the burning of fossil fuels has pumped so much CO2 into the atmosphere that global warming is advancing at a rate that is unprecedented in the past 2,000 years.

Read more: Human influence on global warming is 'unequivocal,' IPCC report says

Carbon factory rainforests

Tropical rainforests are often called the "lungs of the planet" because they produce oxygen and absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). But that pattern has been reversed; the Amazon rainforest is now emitting more CO2 than it absorbs, releasing more than 1.1 billion tons (1 billion metric tons) of CO2 per year, while absorbing only about half a billion tons, according to a July study published in the journal Nature. "Large-scale human disturbances" were responsible for the shift, with wildfires producing much of the excess CO2 — and most of the wildfires were deliberately set in order to clear land for industry and agriculture, the researchers reported.

Read more: The Amazon rainforest is officially creating more greenhouse gases than it is absorbing

'Last Ice Area' melting away

To the north of Greenland lies a frozen zone that previous research suggested would remain mostly frozen even as Earth's climate warmed. But even this so-called Last Ice Area may not survive the current rate of global warming. In 2020, ice cover in the Wandel Sea in the eastern part of the Last Ice Area reached its lowest since record-keeping began, with about 50% of the sea ice melting away during the summer months. When scientists recently analyzed the ice loss, they discovered that year-round melt caused by rising global temperatures was reducing the overall thickness of the region's permanent ice over time. This means that prior models predicting the Last Ice Area's longevity have likely been underestimating the rate of ice loss — and the area could become ice-free as soon as 2040.

Read more: 'Last Ice Area' in the Arctic may not survive climate change

Earthshine gets darker

Scientists recently investigated a previously unexamined consequence of climate change: a decrease in Earth's brightness. Our planet reflects sunlight onto the surface of the moon's dark side, in a phenomenon known as "earthshine." Using satellite views, researchers measured earthshine and tracked variations in brightness based on the reflectiveness of clouds in the atmosphere, and of water, land and snow and ice cover on Earth's surface. They then compared datasets of earthshine observations with other datasets that recorded changes in Earth's cloud cover.

The researchers saw that over the past two decades, Earth's light has dimmed by approximately 0.5% — it now reflects about half a watt less light per square meter. The scientists also found that the dimming corresponded with a decline in bright low-altitude clouds over the eastern Pacific Ocean. Clouds are a complicated piece of the climate puzzle, but this drop is likely linked to other atmospheric changes caused by climate change, the scientists reported in August in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Read more: Climate change is making Earth dimmer

Still not too late

While we can't turn back the clock and reset Earth's climate to conditions that predate the Industrial Age, that doesn't mean there's nothing we can do about climate change. Under the current warming trend, by the year 2050 Earth will become more than 3.6 F (2 C) hotter on average. However, if we reduce fossil fuel use and limit the rise of global temperature averages to no more than 2.7 F (1.5 C) above pre-Industrial levels, we can still slow or stop some of the global changes that are already underway, such as sea level rise and extreme weather events, according to the IPCC report.

If current warming continues, sea level rise could reach 7 feet (2 meters) by 2100. But reducing greenhouse gases and allowing Earth to cool down could slow that process by thousands of years, climate experts wrote in the report. Scientists are also working to develop new computer models to create updated predictions about timescales for ice melt and sea level rise, and to explore how human communities — especially the most vulnerable ones — might adapt to these changes.

But in order to get there, humanity needs to take action, and that begins with dramatically curbing our use of fossil fuels on a global scale, and enacting legislation to rebuild infrastructures around sustainable energy sources, Michael Mann, a climatologist at The Pennsylvania State University previously told Live Science.

"The priority should be on cutting emissions. Getting rid of fossil fuel subsidies is one piece of that. But so are incentives for renewables and carbon pricing," Mann told Live Science in October. "I wouldn't want to put the onus on any of these mechanisms," he added. "We need them all."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus