Could we ever eradicate the flu?

Eradication isn't the only worthwhile goal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For many people, catching the flu might not seem like that big of a deal — you might feel crummy, miss a few days of work or school, and then return to daily life. But this common illness causes tens of thousands of hospitalizations and deaths each year: Between 2010 and 2020, up to 342,000 people died of influenza in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). During three out of the four flu pandemics in the past two centuries, including the 1918 influenza pandemic, that number jumped into the millions worldwide.

Ending this disease would prevent countless deaths. But is it possible to eradicate the flu?

The short answer is no, said Mark Slifka, an immunologist at the Oregon National Primate Research Center. The closest we came to this holy grail of epidemiology was in the 2020-2021 flu season — the first full winter of the coronavirus pandemic, when masking and isolating at home were more common, he said. That season, the CDC reported roughly 150,000 confirmed flu cases (the true number was likely higher), which pales in comparison to the 39 million who contracted the flu during the 2019-2020 season. One type of the flu virus likely went extinct, Slifka said.

"That's exciting, but it doesn't make much of a dent," Slifka said. With the return to air travel, school, work and regular socialization, the flu is back with a vengeance, he said.

That's because influenza viruses, which cause the flu, constantly mutate, creating thousands of versions of themselves; these different versions of the viruses are called "variants" or "strains." If one strain disappears, "others just fill in," Slifka said. Each year brings new influenza variants, which necessitates a new vaccine. That makes it difficult to manufacture a vaccine. To get ready for flu season, scientists have to predict which variants will be dominant in the upcoming season, based on which variants are circulating in humans in the opposite hemisphere.

"It's a guess; sometimes they don't get it right," said Marc Jenkins, an immunologist at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

Related: Why is the flu shot less effective than other vaccines?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some years, the flu virus mutates so quickly that it outpaces vaccine manufacturers. By the time a shot is ready to be administered to the general population, it might not be very effective against the newest variants. And sometimes, the viruses used in the flu vaccine mutate during the manufacturing process; this means that the viruses aren't a "good match" by the time they're killed and added to the vaccine. As a result, the flu vaccine's effectiveness ranges from 10% to 60% from year to year, according to the CDC. In other words, a person who receives the flu vaccine has a 10% to 60% lower chance of getting the flu than someone who did not receive the vaccine. That effectiveness peaks one month after vaccination and then weakens over time, declining by roughly 10% each month.

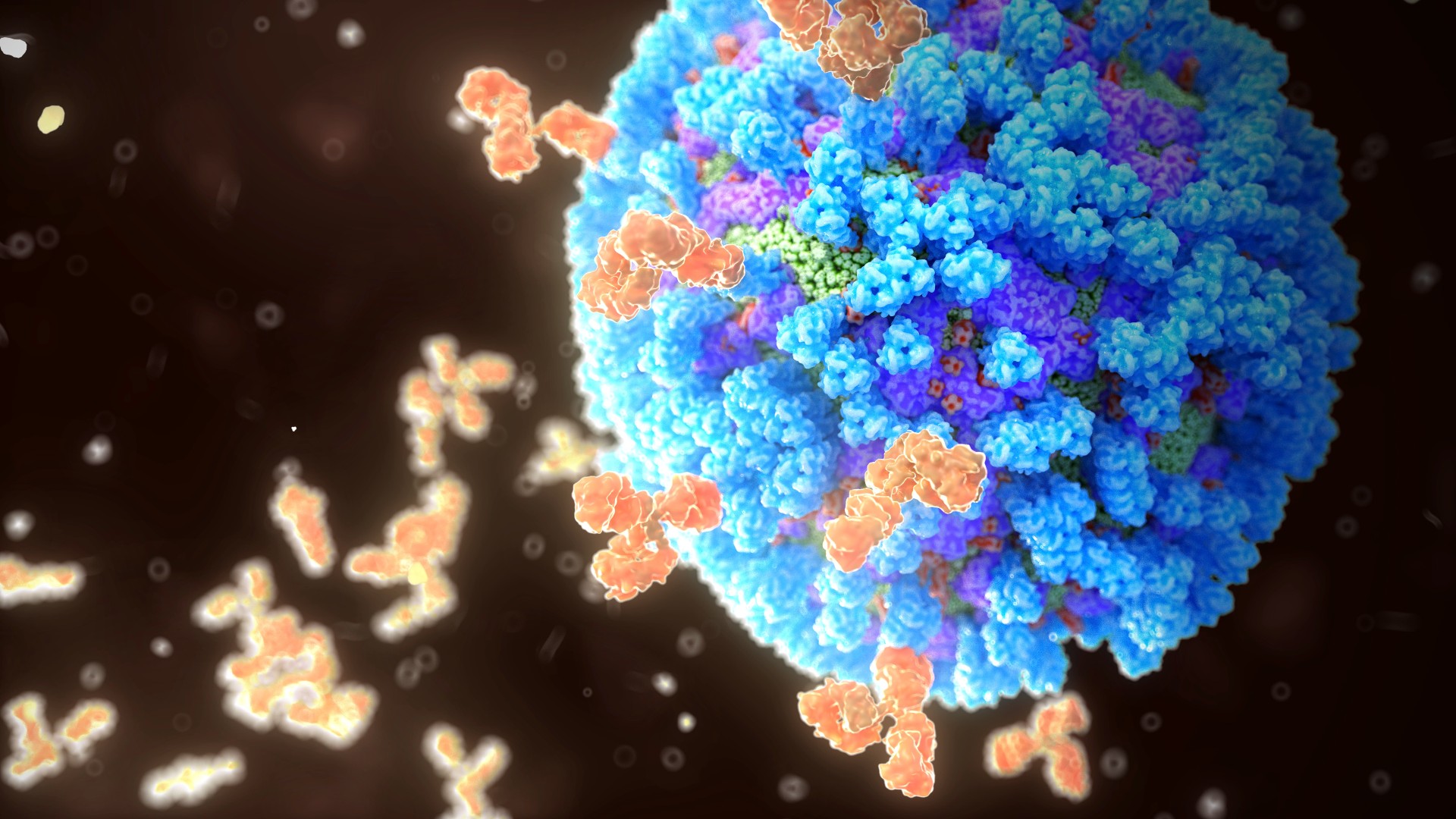

There might be a way to keep up with these rapid mutations, Jenkins said. Some scientists are working on producing a universal flu vaccine — that is, a vaccine that would work against many possible variants of influenza. Currently available flu vaccines present the immune system with a protein from the surface of the flu virus, called hemagglutinin. In response, the immune system produces antibodies, proteins that prevent invading pathogens from hijacking our cells, produced to recognize and target that specific protein.

Here's the problem: the antibodies we produce in response to the flu vaccine tend to recognize just one part of hemagglutinin. This protein is shaped a lot like a piece of broccoli. "The immune system tends to make antibodies against the top part, the broccoli's floret," Jenkins said. Unfortunately, this top part, also called the head, tends to mutate rapidly. In contrast, the "stalk" of the protein doesn't change much — but the immune system pays very little attention to it, producing just a small amount of stalk antibodies.

A universal flu vaccine would teach the immune system to recognize hemagglutinin's stalk, rather than its head. Recently, scientists did just that: They engineered live, weakened versions of influenza to have what they called "chimeric" hemagglutinin. This version of the protein has unusual heads that don't trigger the immune system. No longer distracted by the head, the immune system produces more antibodies in response to the stalk.

Phase I clinical trials for this universal vaccine wrapped up in 2020. The results, published in the journal Nature Medicine, included 51 participants and found that, overall, the vaccine was safe and that vaccinated individuals produced stalk antibodies. However, this trial was very small and didn't measure infection rates in the population, so it's too soon to say whether those antibodies will provide actual protection against the flu. "You can certainly have antibodies and not good protection," Jenkins said.

Related: It's safe to follow the vaccine schedule for babies. Here's why.

Let's say we do eventually adopt a universal vaccine. In one extremely unlikely hypothetical scenario, the vaccine is nearly 100% effective and all humans receive it. Even that wouldn't be enough to eradicate influenza. That's because influenza infects many kinds of animals, and from time to time, it makes the jump from a different species into humans or vice versa — these are called zoonotic infections. Since the first recorded zoonotic influenza outbreak in 1958, scientists have identified 16 zoonotic influenza variants in humans. The 2009 swine flu outbreak was caused by a strain of H1N1, which looked "suspiciously" like the deadly 1918 flu, Slifka said. At some point, this variant had jumped into pigs, combined with a different influenza virus, and then jumped back into humans.

"To stop transmission, we'd have to vaccinate every duck and pig simultaneously," Slifka said. Otherwise, it's feasible that influenza could persist and mutate in a different animal species until it's once again unrecognizable to the human immune system.

A universal flu vaccine isn't the only tool for tackling the flu. Some researchers aim to develop an mRNA vaccine for the flu. Similar to the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, this vaccine would teach the immune system to produce the target protein — hemagglutinin for example — in house, Ryan Langlois, a virologist at the University of Minnesota, told Live Science. These vaccines don't take as long to produce as traditional flu vaccines, and would give scientists more time to guess the next flu season's dominant variants.

Other scientists, including Mark Slifka's team at Oregon Health and Science University, are working to develop more effective vaccines by using intact viral proteins, in contrast to current flu vaccines, which break those viral proteins into small, soluble pieces. With a more effective vaccine or one that protects against more variants, it's possible to prevent hospitalizations and deaths, Jenkins said.

In the end, eradicating the flu isn't the only worthwhile goal, Jenkins said: "It's a high bar. I'm not convinced we need to achieve it in order to have clear benefits."

Originally published on Live Science.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus