Stunning hoard of Bronze Age jewelry discovered by local hiker in Sweden

The hoard likely belonged to an elite woman.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A Bronze Age hoard brimming with fine jewelry was discovered in Sweden in early April, when a local man investigated what he thought was a piece of scrap metal sticking out from under a pile of rocks in a hilly, wooded area.

Tomas Karlsson was doing an outdoor navigation activity called orienteering when he uncovered the stash, located just outside of the municipality of Alingsås in southern Sweden. He quickly realized that the metal wasn't scrap — it was ancient bronze jewelry that had since turned green. It appeared that a wild animal had recently dug up a few pieces, revealing the metal, so Karlsson contacted the local authorities, who told archaeologists about the site, according to Sveriges Radio, Sweden's national publicly funded radio station.

"It's one of the largest hoards we've ever excavated from the late Bronze Age in Sweden," project leader Johan Ling, a professor of archeology at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, told Live Science. "And, indeed, [they're] also very spectacular bronzes and very well-preserved bronzes."

Related: Photos: A Bronze Age burial with headless toads

The entire hoard has about 50 artifacts, and roughly 80% of the items appear to be associated with a high-status woman (or women) from the late Bronze Age, about 2,700 to 2,500 years ago, judging from the style of the objects, Ling said. The team is currently performing radiocarbon dating on charcoal pieces from the sediment where the hoard was found, he added.

The many treasures that were discovered include neck rings, bronze spirals, necklaces, arm rings, pins and ankle rings, as well as the head of an ax. "The interesting thing is [the hoard objects] are not very common in Scandinavia, although they are common in northern Poland and northern Germany," which indicates the existence of a "strong trade network," Ling said.

This hoard isn't part of a human burial, however. Instead, it's a collection of high-status objects that were purposefully buried, Ling said. It's possible that during the Bronze Age, people in this region performed ceremonies that were similar to potlatch, a custom practiced by Indigenous groups such as the Haida and Tlingit in the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and Canada, Ling said. Although potlatch customs vary across the Pacific Northwest, they generally involve a lavish ceremonial feast, often with dancing and singing, during which people give away or destroy parts of their wealth to show their superior generosity and enhance their social standing, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This buried Bronze Age hoard is likely "a self-investment, it's a manifestation of power that these elites are doing, showing that 'We can afford [this], we have this ability, you do not have this,'" Ling said. "[They] believed it showed their power by offering their surplus, so to speak."

It's also possible that the hoard was buried in parallel with an individual at another location, but archaeologists have yet to find a grave, he said. In this scenario, the hoard might have been buried as a type of potlatch, as well as a way to help the deceased in the afterlife, he said.

It's unlikely the hoard was buried for safekeeping or to hide it from enemies, Ling noted.

During the Bronze Age, people in what is now Sweden were farmers and agropastoralists, meaning they had a mix of farming and livestock. Surpluses were often invested in trade, as it was also a known maritime society, "because we do import all metals in Scandinavia at that phase, both copper and tin, and the bronzes are made of 90% copper and 10% tin," Ling said. The copper, for instance, came from the British Isles, the Iberian Peninsula and Central Europe, he noted.

Ling and his colleagues plan to further analyze the hoard. Its peculiar location might be a clue that there are hoards buried in similar spots, he said.

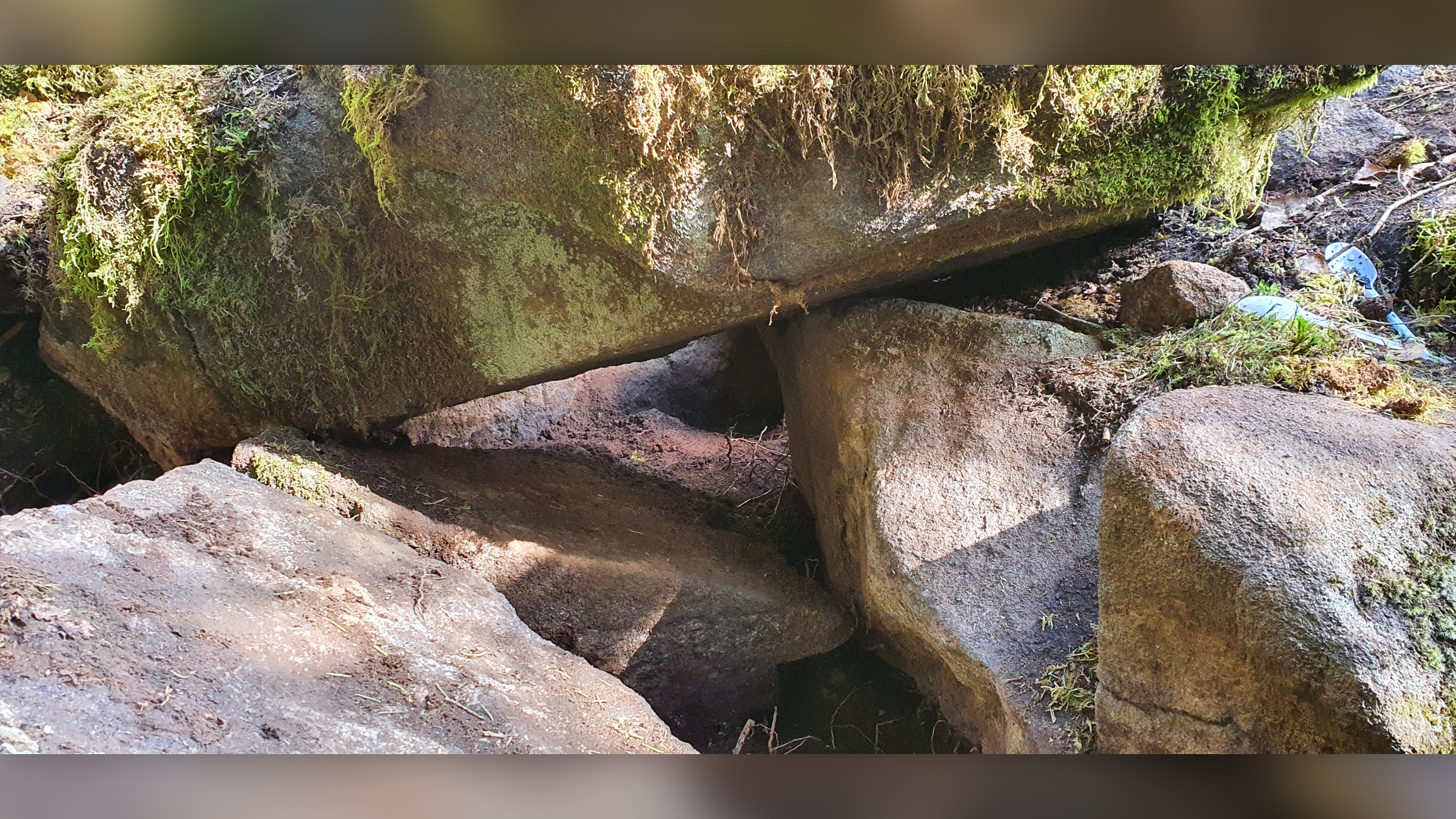

"It was found in a very sloppy, hilly area. I can tell you I would have passed that find and that assemblage of stones a thousand times [without looking there]," Ling said. "But now, we have a new pattern that we have to follow. There could be much more of these that we haven't been able to detect yet."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus