The 10 Biggest Archaeology Discoveries of 2019

A Bronze Age "megalopolis" in Israel, a "cachette of the priests" near Luxor, Egypt, and a massive ancient wall in western Iran are just a few of the many incredible archaeological stories that came to light in 2019. Here, Live Science takes a look at 10 of the biggest archaeology discoveries that emerged this year. As in past years, it was difficult to narrow this list to only 10.

Head-dropping find

The year started off with a heady discovery. Archaeologists found 17 decapitated skeletons, their heads resting between their owner's legs or feet, in a 1,700-year-old Roman cemetery in the village of Great Whelnetham in Suffolk, England.

Their skulls appear to have been removed from their heads after death. "The incisions through the neck were postmortem and were neatly placed just behind the jaw," Andy Peachey, an archaeologist with Archaeological Solutions, the company responsible for excavating the cemetery, told Live Science. "An execution would cut lower through the neck and with violent force, and this is not present anywhere."

No grave goods were found with the headless individuals, though their bones were in good shape, suggesting the individuals were well-nourished. A few of the individuals had tuberculosis, which was common in farming communities at the time.

Why the heads of these people were removed is a mystery. One possibility is that the ancient people there believed that the head was a container of the soul and needed to be removed so one could advance to the afterlife.

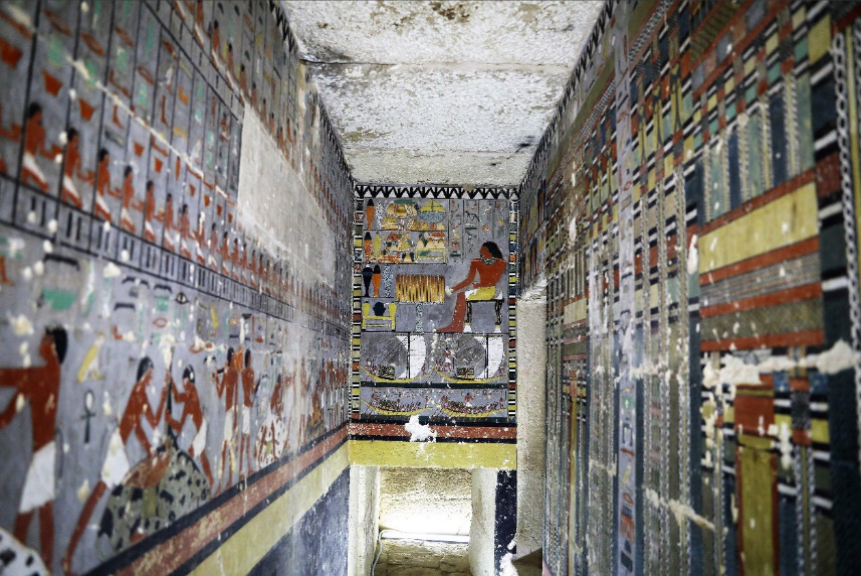

Most colorful tomb

Egypt divulged a wealth of ancient secrets in 2019. By far the most colorful discovery was that of the 4,400-year-old tomb of Khuwy, an official who lived at a time when the pyramids were being constructed in Egypt.

Hieroglyphs found in the tomb reveal Khuwy's many titles included "overseer of the khentiu-she of the Great House," "great one of the ten of Upper Egypt" and "sole friend" of the pharaoh. All these titles indicate that he was an official of some importance.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But what sets this discovery apart is the remarkable preservation of the tomb's colorful paintings. The paintings include depictions of ships at sail, Egyptians working in the fields and complex patterns that are almost impossible to describe in words. The colors bring these paintings to life; and the fact that they are so well preserved, despite the passage of more than 4 millennia of time, is unusual.

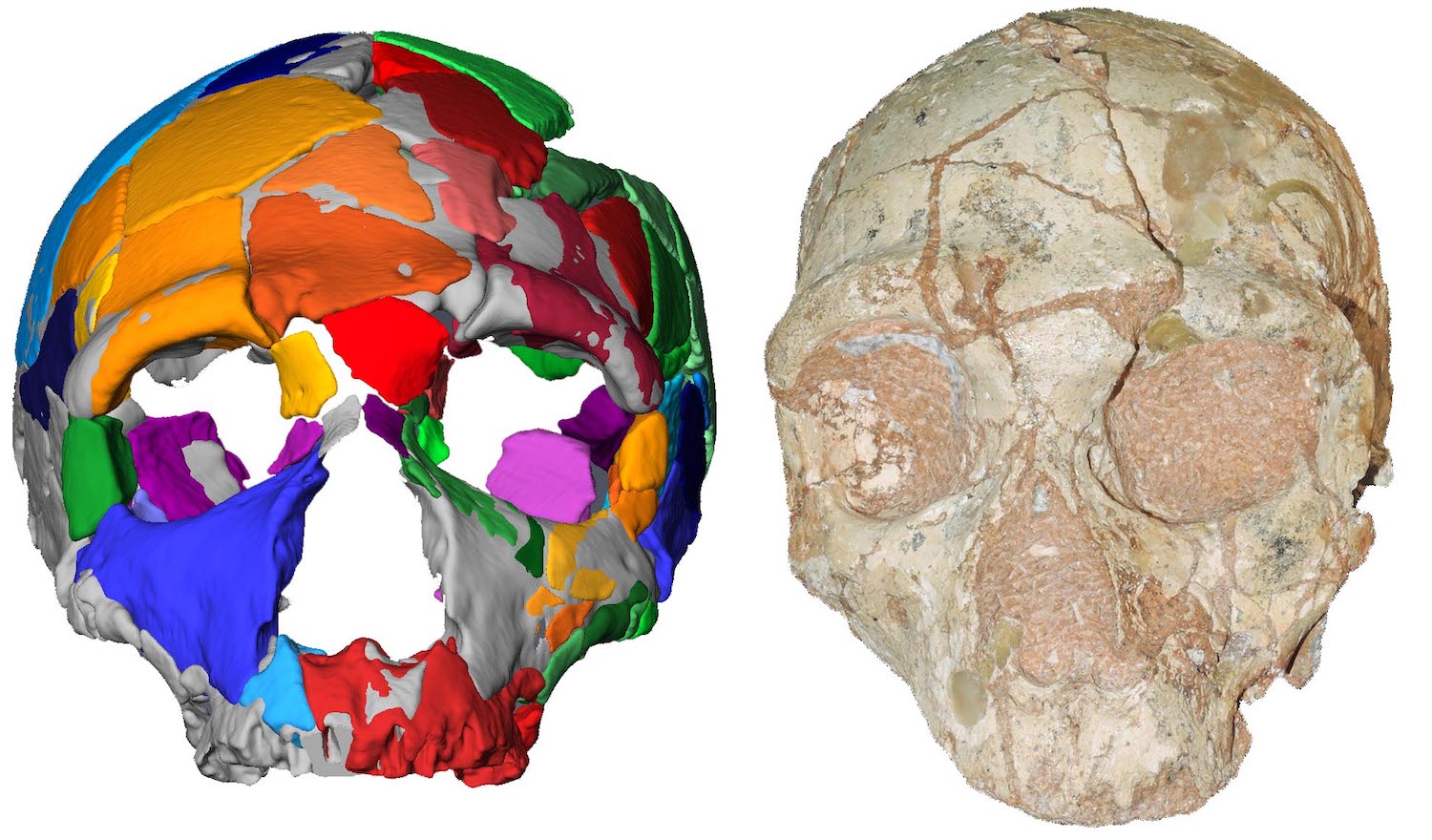

Failed attempt to leave Africa

If at first you don't succeed try, try, again. That's a lesson that Homo sapiens learned about 210,000 years ago, as a skull found in a cave in southern Greece revealed. The skull is the earliest example of a Homo sapiens skull found outside of Africa and reveals a failed attempt by humans to spread beyond Africa, researchers said. But where Homo sapiens, failed Neanderthals succeeded a 170,000-year-old skull found in the same cave reveals that Neanderthals flourished in the region for some time.

It wasn't until much later that Homo sapiens successfully spread outside Africa, the study scientists said. "We know from the genetic evidence that all humans that are alive today outside of Africa can trace their ancestry to the major dispersal out of Africa that happened between 70[,000] and 50,000 years before present," study lead researcher Katerina Harvati, a professor of paleoanthropology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told reporters at a news conference. Homo sapiens eventually became the only hominid species on the planet, with Neanderthals and other hominids becoming extinct.

Valley of the Kings Discoveries

On Oct. 11, 2019, archaeologists in Egypt announced a plethora of discoveries in the Valley of the Kings, where royalty were buried some 3,000 years ago. In the western valley, they found a workshop complex where workers manufactured material for the tombs. There were workshops for coloring pottery, manufacturing furniture and cleaning gold, among many others. They also found a room dug into the valley that was used for mummification, complete with the remains of linen, rope and other materials left over from mummification. They also found a piece of wood with two prongs that may have been used like a forklift to move furniture.

Archaeologists also found new examples of ostraca (pottery with writing on it) that reveal records left behind by the Valley of the Kings workers. They found an area used to bake bread and store food and water. They also found two female mummies near the tomb of the powerful female pharaoh Hatshepsut. To have so many finds made in one year is astonishing and may pave the way for more discoveries in 2020.

Bronze Age "megalopolis"

A 5,000-year-old Early Bronze Age "megalopolis" that was home to around 6,000 people (a large population at the time) was discovered at the site of En Esur in Israel. Millions of pottery fragments, flint tools, basalt stone vessels and a large temple filled with burnt animal bones and figurines were discovered in the city.

One of the figurines depicts a human head with a seal impression on it, showing human hands lifted into the air. The temple had a huge stone basin that held liquids that were probably used for religious rituals. The city's residential and public areas, streets, alleyways and temples appear to have been carefully planned out.

"This is a huge city — a megalopolis in relation to the Early Bronze Age, where thousands of inhabitants, who made their living from agriculture, lived and traded with different regions and even with different cultures and kingdoms in the area," Itai Elad, Yitzhak Paz and Dina Shalem, the directors of the excavation, said in a statement announcing the discovery. They said that the city was the "early Bronze Age New York" of the region.

New Evidence for Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea who presided over the trial of Jesus, has gotten a bad rap throughout history; but in 2019, archaeologists made a find that suggests he may not have been such a bad guy. Archaeologists found that Pilate built a grand street in Jerusalem that stretched for 2,000 feet (600 meters) and connected the Siloam Pool — a place where pilgrims could stop to bathe and get fresh water — to the Temple Mount, the most holy place in Judaism. Researchers were able to tell that the street was built by Pilate because the most recent coins found beneath the street date to A.D. 30-31, a time when Pilate was prefect.

Ancient records say that, in addition to presiding over Jesus' trial, Pilate also seized money from a sacred treasury to build an aqueduct, violated Jewish religious laws and clubbed people protesting his actions. The newly identified street, which would have required 10,000 tons of quarried limestone rock to construct, suggests that Pilate wasn't as corrupt and uncaring as historical records claim. Before this find, very little archaeological evidence linked to Pontius Pilate had been discovered.

Cachette of the Priests

Archaeologists discovered 30 perfectly preserved sealed wooden coffins, dating back 3,000 years, in "El-Assasif," a necropolis near Luxor, Egypt, in 2019. They called the discovery the "cachette of the priests" since some of the mummies appear to be those of ancient Egyptian priests. A cachette is a place where things were hidden away. The vividly colored and complex patterns on the coffins are well preserved despite the passage of 3 millennia.

The mummies within the coffins are also well preserved. When two of the coffins were opened at a news conference, the outer wrappings of the mummies looked untouched. Archaeologists found that 23 adult males, five adult females and two children were buried in the 30 wooden coffins. Analysis of the mummies and translation of the hieroglyphs is ongoing, and more finds about this cache will likely emerge in the next year or two.

It's remarkable that so many sealed coffins, their mummies still intact, were preserved for such a long period of time. Grave robbing was a common occurrence in Egypt in both ancient and modern times.

Huge UK discovery

This 2,200-year-old grave containing the remains of a man who died in his 40s and who was buried with an intricate bronze shield, a chariot and two horses in a "leaping" pose, was hailed as being one of the most important ancient archaeological discoveries ever made in the United Kingdom. The shield is about 30 inches (75 centimeters) across and is decorated with a series of complex swirls and what looks like a sphere protruding from its center.

The man was likely a "a significant member of his society," said Paula Ware, an archaeologist with MAP Archaeological Practice Ltd., who led the team that discovered the grave near Pocklington, England. That it was found intact and excavated using modern archaeological techniques makes the site particularly important, Ware said.

Massive wall

A wall stretching for about 71 miles (115 kilometers) was documented in western Iran. Running north-south between the Bamu Mountains in the north and an area near Zhaw Marg village in the south, it took an estimated 1 million cubic meters [35,314,667 cubic feet] of stone to build. While local people and a few archaeologists had known about the existence of the wall, it had never been described in a journal until this year when an article in the journal Antiquity, written by Sajjad Alibaigi, an assistant professor of Iranian archaeology at Razi University in Kermanshah, Iran, was released.

"Remnants of structures, now destroyed, are visible in places along the wall. These may have been associated turrets [small towers] or buildings," Alibaigi wrote. He noted that the wall is made from "natural local materials, such as cobbles and boulders, with gypsum mortar surviving in places."

It's not clear when the wall was built, who built it or why. Pottery found beside the wall suggests that it was constructed between the fourth century B.C. and sixth century A.D., Alibaigi wrote. The Parthians (who ruled between 247 B.C. and A.D. 224) and the Sassanians (A.D. 224-651) are two empires that flourished in the area, and either one of them could have built the wall.

Helmets from the skulls of kids

Two infants, buried about 2,100 years ago, were found with "helmets" made from the skulls of other children. The two infants with helmets were found buried with the remains of nine other people at the site of Salango, on the coast of central Ecuador.

The helmets were placed tightly over the infants' heads, the archaeologists found. It's likely that the older children's skulls still had flesh on them when they were turned into helmets, because without flesh, the helmets likely would not have held together, the archaeologists noted.

Archaeologists say that this is the only known case in which children's skulls were used as helmets for buried infants. It's not clear what killed the infants or the children. It's also not clear why these helmets were placed on the infants. It "may represent an attempt to ensure the protection of these 'presocial and wild' souls," the archaeologists wrote in a paper published in the journal Latin American Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus