Weathered face of 'old man' Neanderthal comes to life in amazing new facial reconstruction

A new facial reconstruction depicts a Neanderthal whose skeleton was found by priests in a French cave.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 1908, a group of Catholic priests discovered what looked like the skeletal remains of a man buried inside a cave in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, a commune in south-central France. The nearly complete skeleton lacked several teeth, earning him the nickname the "old man."

However, further investigation by scientists revealed that the skeleton wasn't a modern human (Homo sapiens) but rather a Neanderthal, a close relative that went extinct approximately 40,000 years ago.

The skeleton had many hallmark traits of a Neanderthal, including an oversize brow ridge, a flat cranial base and large eye orbits, according to eFossils.com, a site run by the University of Texas at Austin’s Department of Anthropology.

Now, 115 years later, forensic artists have created a digital facial approximation of the Neanderthal, who lived to be about 40 years old, offering a glimpse of what he may have looked like when he lived sometime between 47,000 and 56,000 years ago, according to a new facial approximation that researchers unveiled at a conference presented by the Italian Ministry of Culture in October.

Related: Facial reconstructions help the past come alive. But are they accurate?

For the facial approximation, a forensic artist used existing computed tomography (CT) scans of the skull and then imported measurements along the Frankfort horizontal plane (a line that passes from the bottom of the eye socket to the top of the ear opening) based on a human skull pulled from a database of donors. This gave researchers the necessary framework to generate the face shape.

Next, artists used soft-tissue thickness markers in living human donors to digitally build the "old man's" skin and muscles. They then enhanced the approximation to make it more lifelike by adding details such as color to the skin and hair. It wasn't clear from the research whether these colors were based on a DNA analysis or an educated guess.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

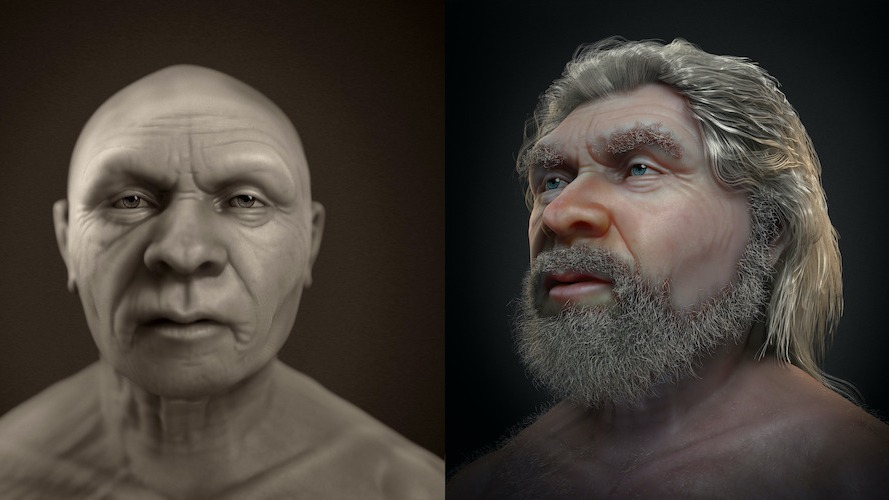

"We generated two images, one more objective with just the bust in sepia tone without hair and another more speculative [and] colorful with a beard and hair," study co-author Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, told Live Science in an email. "This image shows how Neanderthals were similar to us, but at the same time they were different, with more obvious peculiarities such as the absence of a chin, for example. Even so, it is impossible not to look at the image and try to imagine what that individual's life was like, thousands of years ago."

While this isn't the first time that artists have attempted to create a facial approximation of this Neanderthal, it's novel in that researchers used CT scan data to make the image.

Previous (inaccurate) reconstructions have looked exaggeratedly ape-like, such as a 1909 drawing by Czech painter František Kupka and a hunched-over skeleton created by French paleontologist and anthropologist Marcellin Boule, according to Linda Hall Library, an independent science research library in Kansas City, Missouri.

Having the CT scan's digital measurements readily available helped inform the new research team's accuracy and provided new insight into one of modern humans' relatives.

"If one carefully observes the approximations offered over the years, spanning almost over one century, it can be seen how the facial traits of this Neanderthal man have been softened and 'humanized,' abandoning a more brutal perception or interpretation of it, which characterized the idea past anthropologists once had of Neanderthals," study co-author Francesco Galassi, an associate professor of physical anthropology at the University of Lodz in Poland, told Live Science in an email. For instance, in recent decades, research has shown that Neanderthals buried their dead, made tools, used fire to cook food and may have even had ritual practices.

He added, "This change in perception can certainly be attributed to numerous advances in the study of Neanderthals that have shown how they were much closer in anatomy — hence likely in physiology — to us, the anatomically modern Homo sapiens. Our reconstruction offers a new perspective on this ancient man and reflects on this evolving notion."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus