Cannibalism was a common funerary rite in northwest Europe near end of last ice age

Research suggests cannibalism was a funerary rite for the Magdalenian people in northwest Europe, but others preferred to bury their dead.

Cannibalism was common in northwest Europe between 14,000 and 19,000 years ago, when a population of prehistoric people known as the Magdalenians used it in their rituals to dispose of the dead, a new study finds.

But cannibalism seems to have ended when the Magdalenians were supplanted by another group of prehistoric people known as the Epigravettians, who instead buried their dead.

The researchers examined evidence of Magdalenian cannibalism in human remains unearthed at Gough's Cave in western England dating to about 15,000 years ago.

The remains show clear cut marks and indentations made by human teeth. Some of the largest bones have been broken, presumably to scoop out their marrow, and several skull fragments found there have been shaped into cups or bowls, which were probably used for drinking.

"The question has always been, is this cannibalistic behavior exclusive to Gough's Cave?" study co-author Silvia Bello, an archaeologist and anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science. "Was it something strange that happened during a very bad winter, or was it something more?"

Related: Scientists discover what could be the oldest evidence of cannibalism among ancient human relatives

Cultural cannibalism

Bello and William Marsh, a postdoctoral researcher at the Natural History Museum, investigated this question by reviewing human remains from this time; their research was published in the November issue of the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

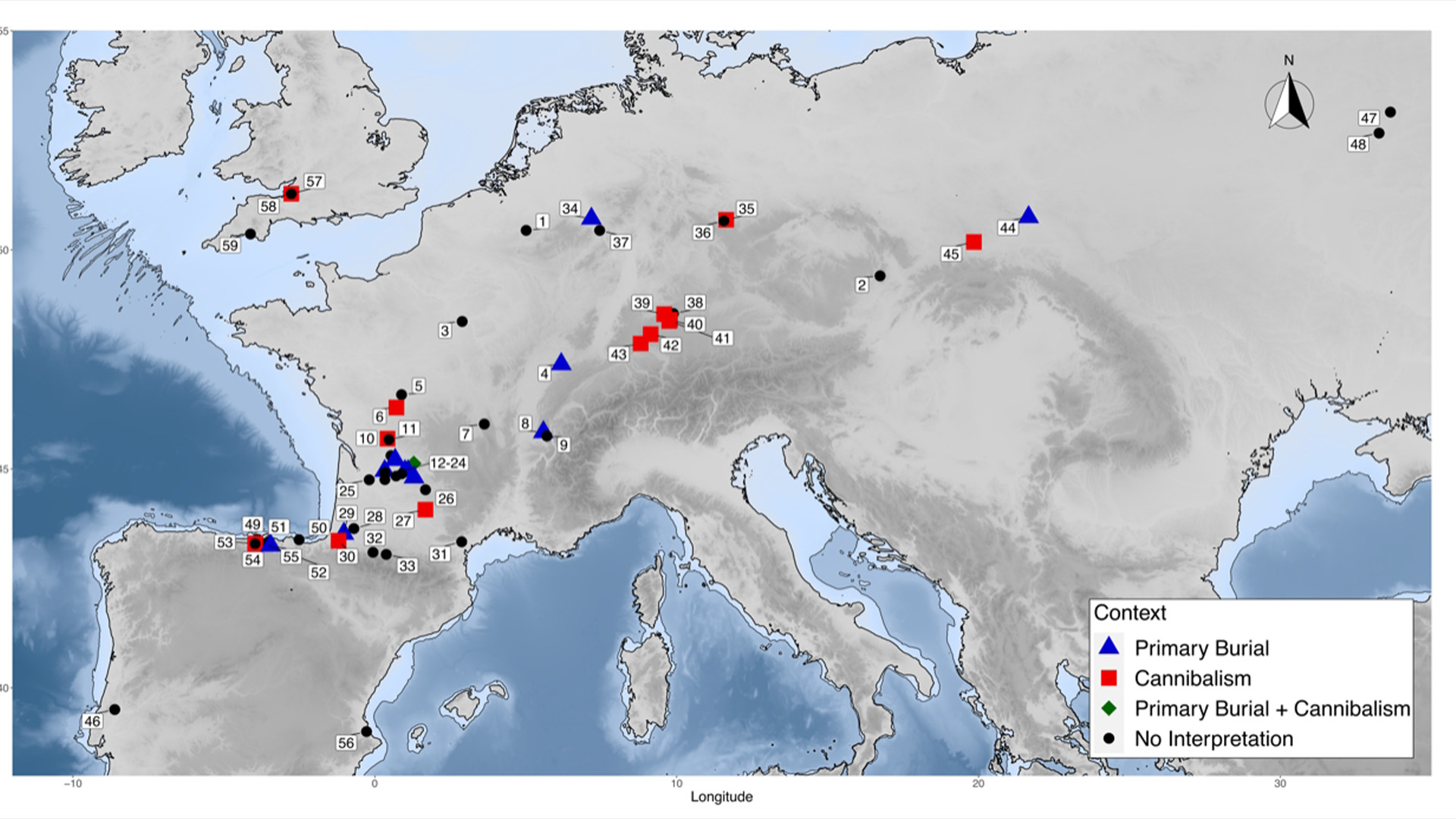

They found widespread evidence of cannibalism throughout northwest Europe at this time, which is known as the Upper Paleolithic period. But they also found a curious cultural link: Genetic research suggests cannibalism was widespread among Magdalenian groups in northern and western Europe but not among Epigravettian groups, who occupied eastern and southern Europe, Bello said.

Bello noted that the conclusions hinge on a small genetic sample — the ancestry of just eight individuals could be reliably determined from their remains.

"I'm very happy to do more studies and be completely wrong," she said.

The researchers also found signs that Epigravettian groups later moved into areas once populated by Magdalenian groups, leading to a dramatic decline in funerary cannibalism.

Stone-Age Europe

The Magdalenians were hunter-gatherers who occupied much of northwest Europe between 17,000 and 12,000 years ago, when the climate was much cooler than it is today. They are named after a rock shelter in the Dordogne region of southwest France where thousands of their artifacts have been found, including a famous engraved antler that shows a bison licking an insect bite.

Early archaeologists identified the Magdalenians as "reindeer hunters," although their sites show they also hunted horses, bison and other large mammals.

Roughly at the time the Magdalenians lived in northern and western Europe, the Epigravettians lived in southern and eastern Europe. They are named after the much earlier Gravettian culture of Europe from which they're thought to have descended.

Archaeologist James Cole, an expert on cannibalism at the University of Brighton in the U.K., told Live Science that the new study gave a "fine-grained look" at the two populations co-existing in the region. But he said the data can only hint that Epigravettian burial culture ultimately replaced the cannibalistic Magdalenian one, because the genetic sample was so small. Michael Pante, a paleoanthropologist at Colorado State University who also wasn't involved in the study, agreed. "The statistical power of what they're saying is very weak," he told Live Science. "Whether it's true or not, they need more data to say it."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus