World's oldest known case of cannibalism revealed in trilobite fossils

The trilobite Redlichia rex likely chomped on its own kind.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

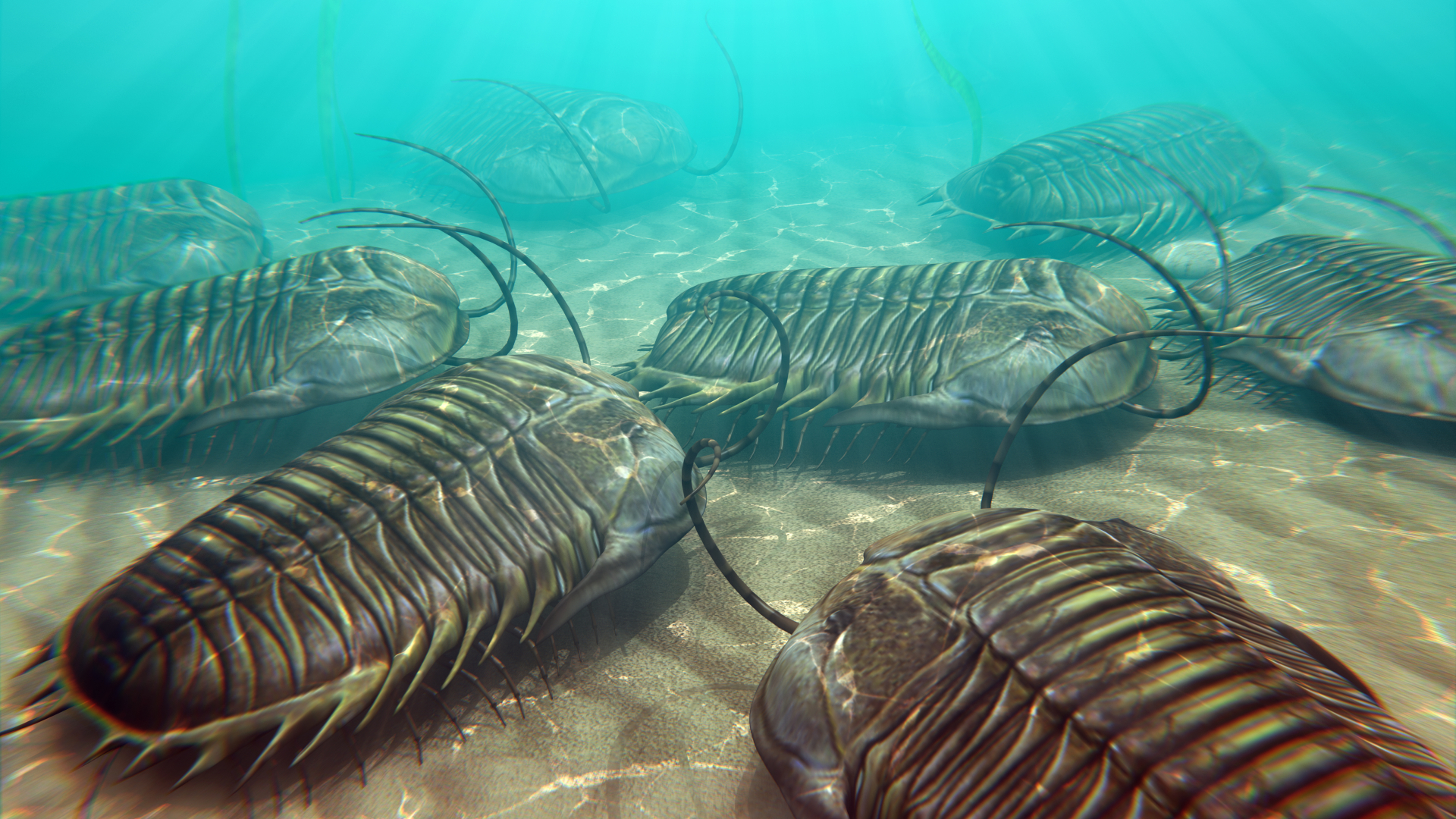

It's a dog-eat-dog world out there. But before there were dogs — or even dinosaurs — there were trilobites brutally biting each other on the Cambrian seafloor. New research has revealed that these armored predators didn't only hunt smaller and weaker animals for food, but would occasionally take bites out of their trilobite comrades of the same species. This finding represents the earliest evidence of cannibalism in the fossil record to date.

Trilobites are now-extinct marine arthropods that first appeared in the fossil record around 541 million years ago. They were stout creatures with thick exoskeletons, which is likely one of the reasons so many trilobite fossils remained preserved all these years; exoskeletons fossilize much easier than softer tissues.

Russell Bicknell, a paleontologist at the University of New England in Australia, spent five years examining trilobite fossils from the Emu Bay Shale formation on Kangaroo Island in South Australia. There are two trilobite species from the same genus found in this formation: Redlichia takooensis, a deposit feeder that ate particles on the ocean floor, and the larger, predatory R. rex.

Many of the R. takooensis fossils were found with what appeared to be bite marks, mostly on their hind ends. This was expected, as paleontologists already knew that R. rex made meals of R. takooensis. In the Emu Bay formation, fossilized feces, called coprolites, left behind by R. rex contain trilobite shell remnants. This suggests that R. rex had the capability of eating the smaller trilobite species. What was unexpected, though, were signs of similar bite marks on R. rex. These injuries, the researchers concluded, were likely the result of cannibalism.

Related: Why did trilobites go extinct?

"There's not much else in this deposit that has the toolkit, is biomechanically optimized for this kind of thing, and could willingly crunch down on something hard," Bicknell told Live Science. While not much is known about trilobite mouthparts, Bicknell is certain that these injuries weren't "bites" in the traditional sense. Instead, the underside of a trilobite featured two rows of legs, and on these legs were little inward-facing spines. If you have ever eaten crab legs or lobster, then imagine an animal with legs like the tool modern chefs use to crack open these shells. R. rex was born to hunt trilobites, and apparently it didn't matter much which species.

Most of the injuries seen on the Emu Bay fossils were injuries to the abdomen and not the head. Bicknell believes this is because the injured animals were trying to get away from their predator's clutches, but he also suggests there may have been a bit of survivorship bias at play too. The injured fossils are from the animals that got away — they weren't eaten. Trilobites that sustained head injuries likely ended up as coprolites.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While this is the earliest documented example of cannibalism for any animal in the fossil record, Bicknell said it's likely that cannibalism is much older and more widespread than even these fossils suggest.

"I would go as far as to say that arthropods have been eating arthropods since the dawn of arthropods becoming arthropods," Bicknell said. However, direct evidence of such ancient cannibalism has not been available in the fossil record, until now.

While it is difficult to prove that cannibalism took place, Bicknell and his colleagues were able to systematically remove all other explanations for the injuries found in R. rex fossils. "What you're left with is this almost demonstrable record of cannibalism, just short of going back in time and watching it happen," said Bicknell.

This research was published April 1 in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Cameron Duke is a contributing writer for Live Science who mainly covers life sciences. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and is an adjunct instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, teaching biology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus