3,300-year-old ancient Egyptian whistle was likely used by police officer tasked with guarding the 'sacred location' of the royal tomb

Archaeologists in Egypt have unearthed a 3,300-year-old bone whistle carved out of a cow's toe, and it may have been used by an ancient "police officer."

A 3,300-year-old whistle carved out of a cow's toe bone has been discovered in Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna), an ancient Egyptian capital founded by the father of King Tutankhamun.

It is the first bone whistle to be found from ancient Egypt and was likely used by a "police officer" who was monitoring workers of a royal tomb thousands of years ago, according to a new study.

"It is very unique," study co-researcher Michelle Langley, an associate professor of archaeology at Griffith University in Australia, told Live Science in an email.

Archaeologists with the Amarna Project discovered the whistle in 2008 while excavating a site within Akhetaten, but hadn't analyzed it until recently. The city is famous for its founder, the pharaoh Akhenaten, who forbade worship of Egypt's many gods except for Aten, the sun disk. But the capital, established circa 1347 B.C., lasted only about 15 years and was abandoned after the pharaoh's death. Later, King Tut reintroduced the Egyptian pantheon to the kingdom.

The whistle, "a very unassuming artefact," sheds light on the activities of the city's nonroyal inhabitants, Langley said. The bone has a single hole drilled into it, and it "fits comfortably in your palm," she said.

In an experiment, the researchers made a replica out of a fresh cow toe bone and found that the "natural form of the end of the bone creates the perfect surface to rest your lower lip so you can blow across the hole," Langley said.

Related: 30 incredible treasures discovered in King Tut's tomb

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A view of the more than 0.2-inch-long (6 millimeters) hole in the bone whistle, which was crafted from the toe of a juvenile cow (genus Bos).

The bone whistle is about 2.5 inches long (6.3 centimeters) and fits comfortably in a person's hand.

A view of the landscape at Stone Village where archaeologists found the whistle.

Police whistle

The researchers found the whistle at a site known as the Stone Village, which is near another site called the Workman's Village. Both villages likely housed workers involved in the creation of the royal tomb, according to the research team, which was directed by University of Cambridge archaeologists Anna Stevens and Barry Kemp.

Previous excavations revealed that the villages had a complex network of roadways next to a series of small structures, which may have been good vantage points for officers to watch over the area, the researchers wrote in the study, which was published Sept. 1 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

"This area appears to have been heavily policed in order to keep the sacred location of the tomb known and accessed by only those that need to know and go there," Langley said.

In particular, the whistle was found in a structure that the team had interpreted as being some kind of checkpoint for people coming in and out of the Stone Village, Langley said, so "the whistle being used by a policeman or guard makes the most sense."

At another famous site, Deir el-Medina — the village of tomb workers for the Valley of the Kings — tomb workers were policed in a similar way, she said. And other New Kingdom artifacts, such as texts and images, reveal that the Egyptians had police officers known as "medjay."

"The medjay were a semi-nomadic group of people originally from the desert region and who were well-known for their elite military skills," Langley said. "They were used by the Egyptians as a kind of elite police force."

Further clues suggest that the newfound whistle was used by a police officer. For example, the decorated tomb of Mahu, the chief of police at Akhetaten, was previously uncovered in the area.

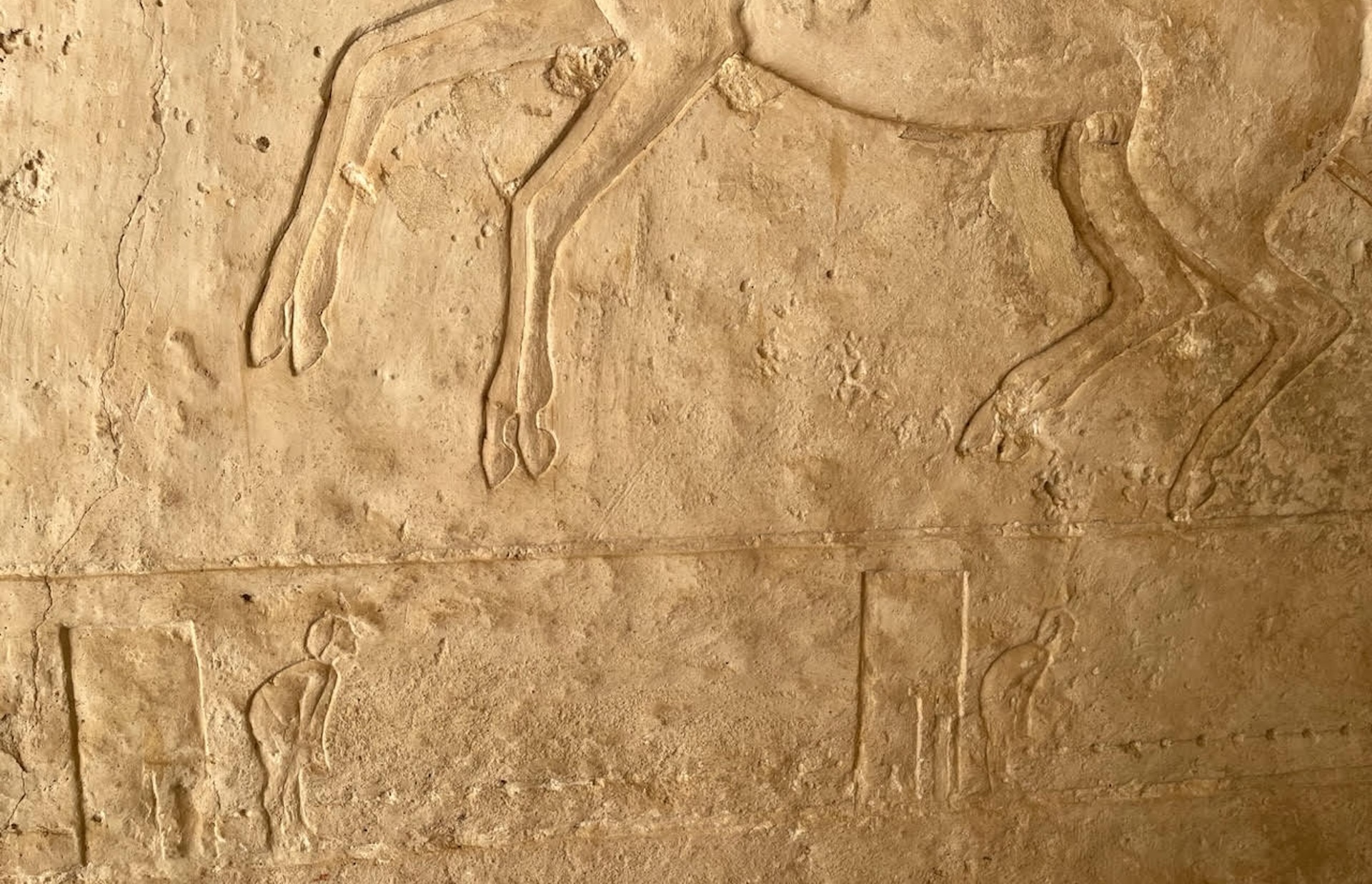

The tomb of Mahu, chief of police at Akhetaten, shows what may be sentries guarding different watch posts.

A detail from the tomb of Mahu showing possible guards overseeing watch posts.

"In his tomb, one scene shows police holding men in custody — apparently having been caught trying to sneak into the city," Langley said. "In other scenes, we see a series of sentries standing along what might be a roadway like that around the villages."

In another image in Mahu's tomb, sentries stand guard at small structures that may be checkpoints. "So, we do know that police were actively guarding the boundary and areas of the city," Langley said.

When Langley first saw the whistle, it reminded her of bone-carved whistles from Stone Age Europe. After ruling out other uses for the Egyptian artifact, such as being a game piece, Langley and her colleagues were excited that they had documented ancient Egypt's first known whistle.

"While there has been a lot of attention given to the tombs and monuments built by the Pharaohs, we still know relatively little about the more average person," Langley said. Sites like Amarna are so important because they record "the lives not only of Pharaoh and his court, but also the regular, everyday people."

Ancient Egypt quiz: Test your smarts about pyramids, hieroglyphs and King Tut

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus