'We were freaking out': Scientists left 'flabbergasted' by detailed dinosaur footprints covering a cliff in Alaska

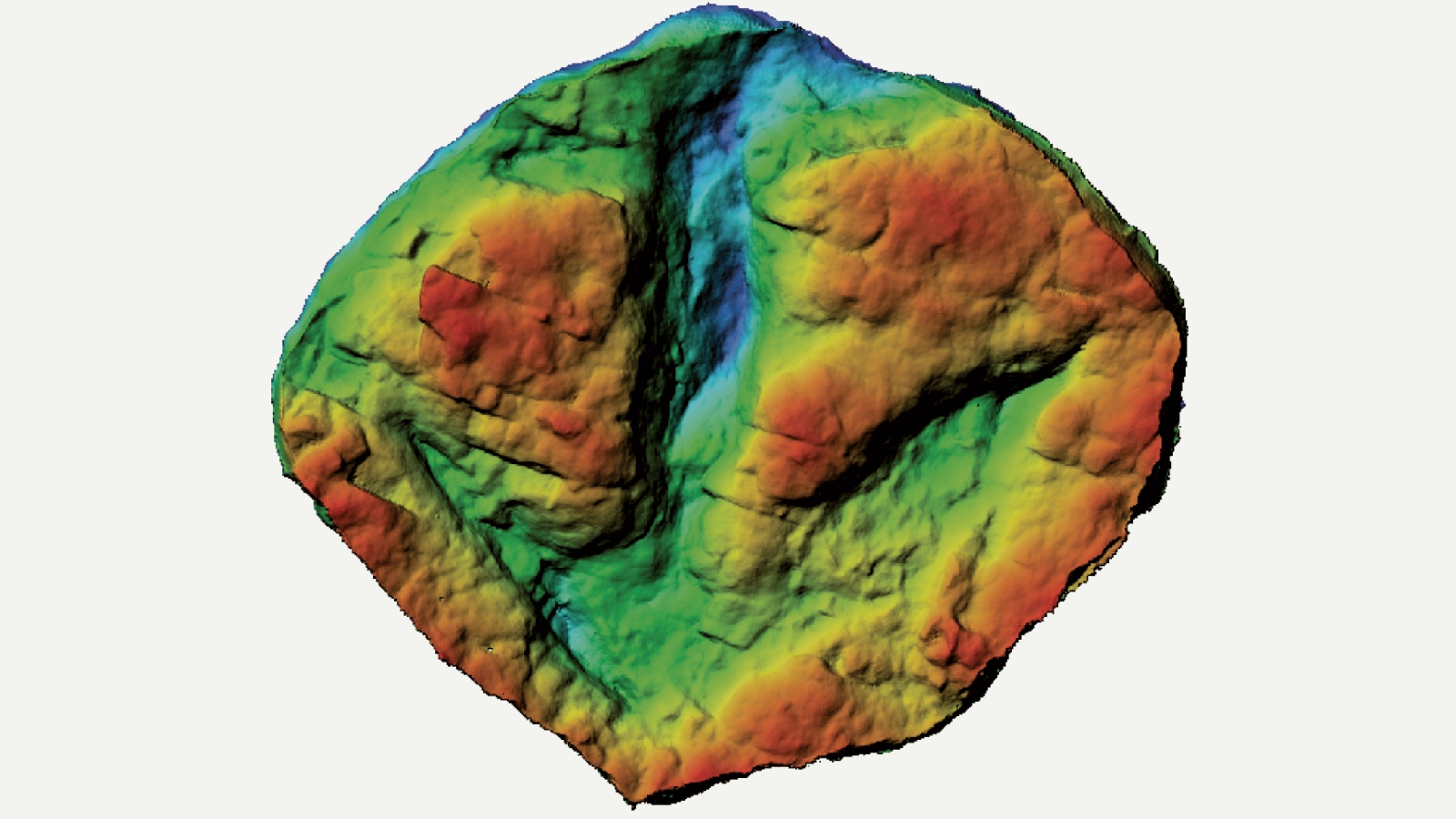

A 20-story rock face in Alaska known as "The Coliseum" is covered with layers of footprints belonging to a range of dinosaurs, including a tyrannosaur.

"Flabbergasted" researchers have discovered that the face of a 20-story cliff in Alaska is covered in the fossilized footprints of dozens of dinosaurs, giving the impression that the creatures defied gravity to walk across its surface, though a geological process is actually to blame.

The rock face, located in Denali National Park and Preserve, currently stands around 218 feet (66 meters). But around 70 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous period, the rock was muddy sediment that likely surrounded a watering hole on a large floodplain. This likely explains the diverse array of dinosaur prints in the cliff face — including the juveniles and adults of various large, plant-eating, duck-billed and horned dinosaurs, as well as carnivores such as raptors, nonavian flying reptiles and at least one tyrannosaur.

Long after the dinosaurs had left their mark in the area, the tracks were lifted up and dumped on their side as the ground bulged upward during a tectonic plate collision, similar to how the hood of a car buckles under the force of a collision. This tectonic activity was part of the geological commotion that birthed the 600-mile-long (966 kilometers) Alaska Range near Denali National Park, according to the National Park Service.

Researchers have nicknamed the site "The Coliseum" due to the array of dinosaurs that likely mingled with one another at the water's edge. The team's analysis of the site was published July 27 in the journal Historical Biology. (A coliseum can be a theatre, stadium or other large public space.)

Related: 4-year-old discovers impressive dinosaur footprint on Wales beach

The cliff is part of a massive rocky outcrop that is around a seven-hour hike from the nearest road. Other researchers had previously discovered a set of tracks at the base of the cliff but missed the complex patchwork of footprints looming above them, mainly because most had been filled in by other sediments. But when their colleagues visited the site they spotted the hidden tracks.

"When we first went out there, we didn't see much either," study co-author Pat Druckenmiller, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and curator at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, said in a statement. But in a certain light, the footprints became much more visible.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When the sun angles itself perfectly with those beds, they just blow up," study lead author Dustin Stewart, a paleontologist at Paleo Solutions and a former student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said in the statement. "Immediately all of us were just flabbergasted," he added. "We were freaking out."

Upon closer inspection, the team realized that the footprints were incredibly detailed. "They are beautiful," Druckenmiller said. "You can see the shape of the toes and the texture of the skin."

The researchers also discovered even more tracks layered beneath those on the rock's surface.

"It's not just one level of rock with tracks on it," Stewart said. "It is a sequence through time." Other dinosaur tracks have been found in Denali National Park but "nothing of this magnitude," he added.

The cliff also contains fossilized plants, pollen and shellfish, as well as footprints left behind by wading birds. The researchers hope these finds will help them paint a detailed picture of the ecosystem 70 million years ago. "All these little clues put together what the environment looked like as a whole," Stewart said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus