Never-before-seen 'mud mummy' from Egypt discovered in wrong coffin

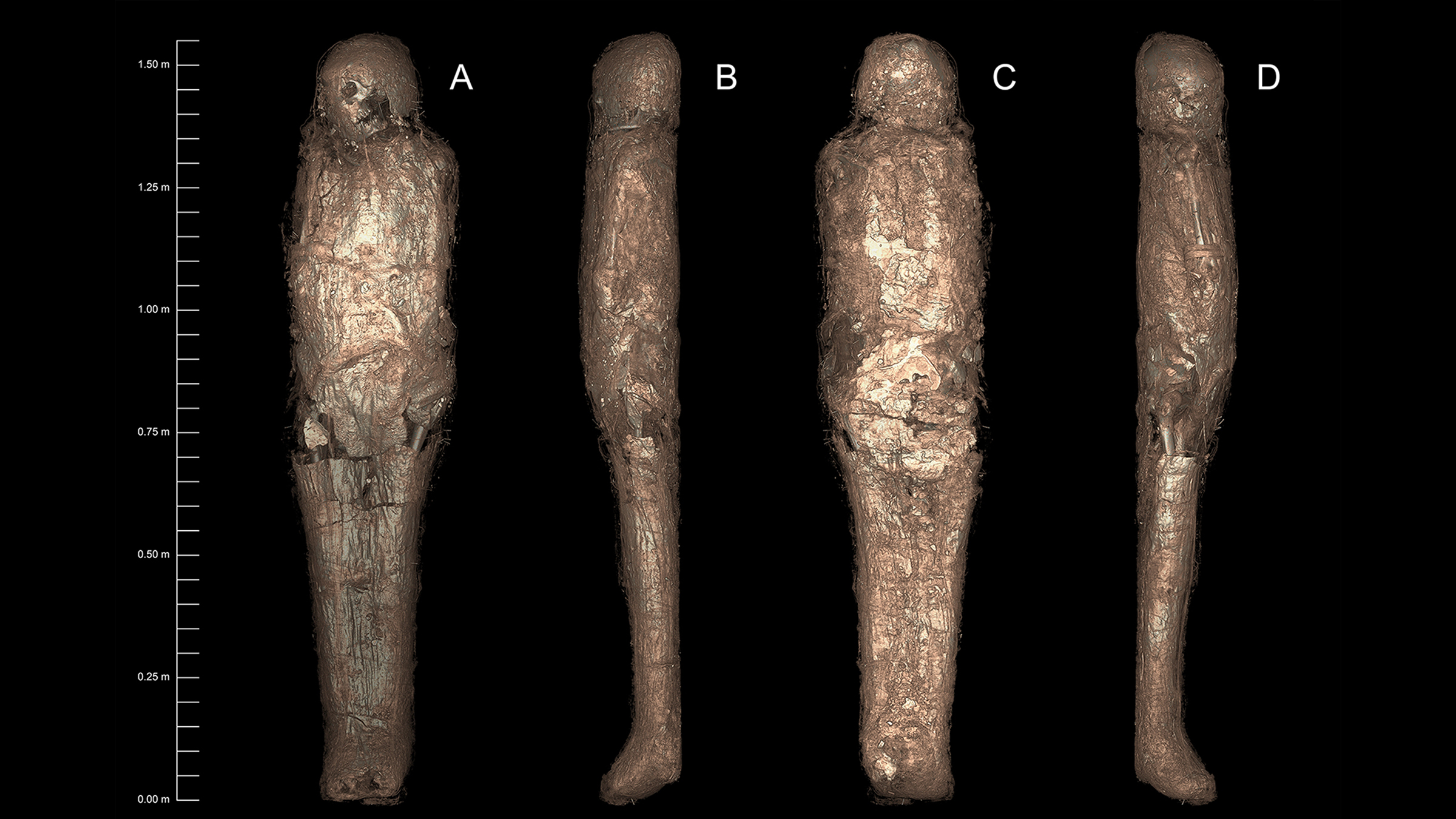

This is the only known mud-wrapped ancient Egyptian mummy.

The discovery of a rare "mud mummy" from ancient Egypt has surprised archaeologists, who weren't expecting to find the deceased encased in a hardened mud shell.

The "mud carapace" is an unparalleled find; it reveals "a mortuary treatment not previously documented in the Egyptian archaeological record," the researchers wrote in the study, published online Wednesday (Feb. 3) in the journal PLOS One.

It's possible the "mud wrap" was used to stabilize the mummy after it was damaged, but the mud may have also been meant to emulate practices used by society's elite, who were sometimes mummified with imported resin-based materials during a nearly 350-year period, from the late New Kingdom to the 21st Dynasty (about 1294 B.C. to 945 B.C.), the researchers said.

So, why was this individual covered with mud, rather than resin? "Mud is a more affordable material," study lead researcher Karin Sowada, a research fellow in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, told Live Science in an email.

The mud sheath isn't the mummy's only oddity. The mummy, dated to about 1207 B.C., was damaged after death, and was even interred in the wrong coffin actually meant for a woman who died more recently, the researchers found.

Related: Image gallery: Mummy evisceration techniques

Like many ancient Egyptian mummies, the "mud mummy" and its lidded coffin were acquired in the 1800s by a Western collector, in this case, Sir Charles Nicholson, an English-Australian politician who brought it to Australia. Nicholson donated them to the University of Sydney in 1860, and today they reside at the university's Chau Chak Wing Museum. But it appears that whoever sold the artifacts tricked Nicholson; the coffin is younger than the body buried in it, the researchers found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Local dealers likely placed an unrelated mummified body in the coffin to sell a more complete 'set,' a well-known practice in the local antiquities trade," the researchers wrote in the study. The coffin is inscribed with a woman's name — Meruah or Meru(t)ah — and dates to about 1000 B.C., according to iconography decorating it, meaning the coffin is about 200 years younger than the mummy in it.

While the individual isn't Meruah, anatomical clues hint that it is a female who died between the ages of 26 and 35, the researchers said.

Muddy treatment

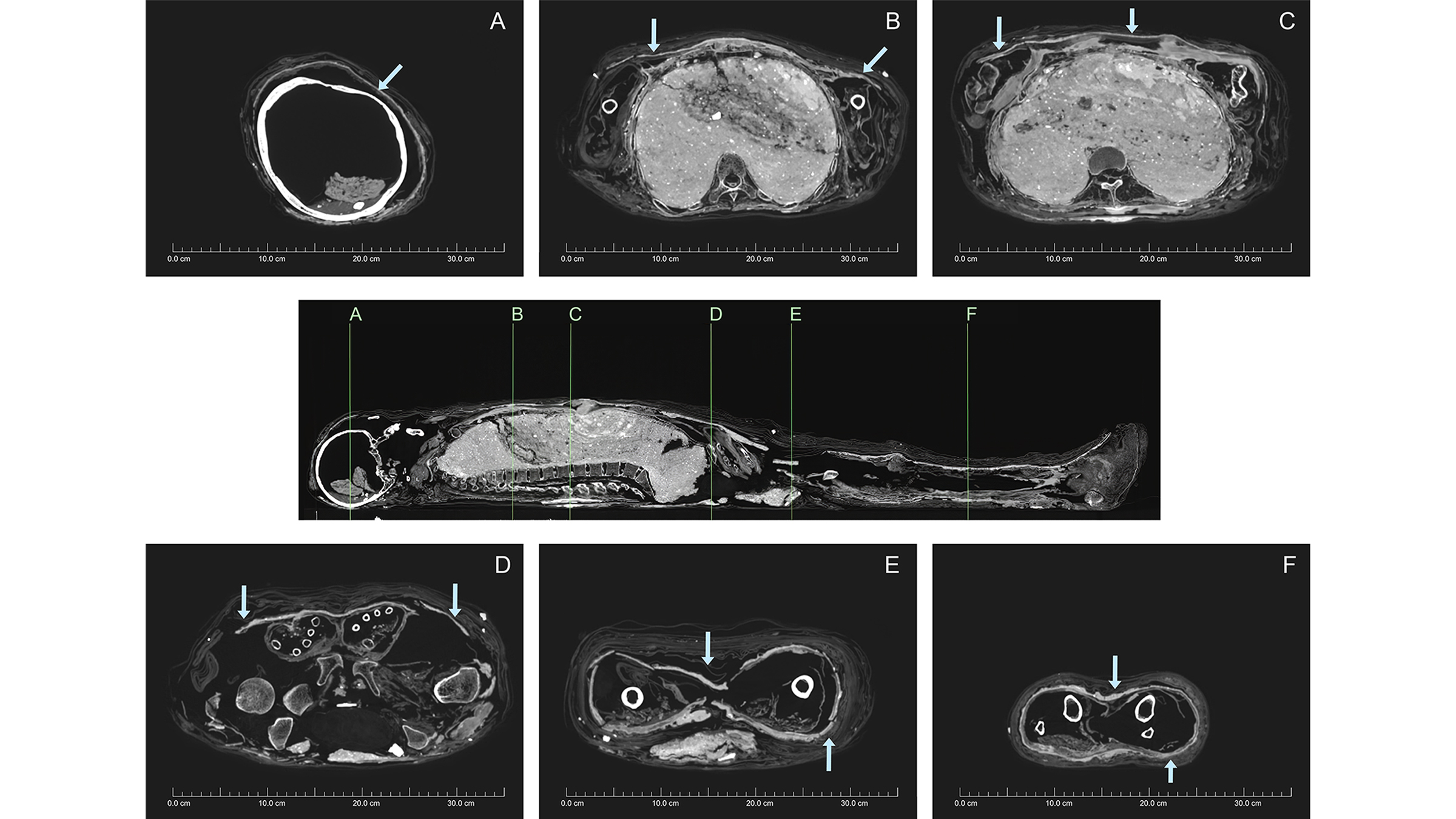

Researchers got their first inkling that the 3,400-year-old mummy was unusual in 1999, when a CT (computed tomography) scan revealed something strange inside. To investigate, the researcher extracted a few samples of the wrappings and discovered they contained a sandy mud mixture. When a new team of researchers re-scanned the mummy in 2017, they uncovered previously unknown details about the carapace, especially when they chemically reexamined the mud fragments.

After she died, the woman was mummified and wrapped in textiles. Then, her remains, including her left knee and lower leg, were damaged in "unknown circumstances," possibly by grave robbers, which prompted someone to repair her mummy, likely within one to two generations of her first burial — a feat that included "rewrapping, packing and padding with textiles, and application of the mud carapace," the researchers wrote in the study.

Whoever repaired the mummy made a complicated earthy sandwich, placing a batter of mud, sand and straw between layers of linen wrappings. The bottom of the mud mixture had a base coat of a white calcite-based pigment, while its top was coated with ochre, a red mineral pigment, Sowada said. "The mud was apparently applied in sheets while still damp and pliable," she said. "The body was wrapped with linen wrappings, the carapace applied, and then further wrappings placed over it."

Related: In photos: The life and death of King Tut

Later, the mummy was damaged again, this time on the right side of the neck and head. Because this damage affects all of the layers, including the muddy carapace, it appears this damage was more recent and prompted the insertion of metal pins to stabilize the damaged areas at the time, the researchers said.

This "mud mummy" isn't the only ancient Egyptian mummy subject to post-mortem repair; the body of King Seti I was wrapped more than once, and so were the remains of King Amenhotep III (King Tut's grandfather), the researchers noted.

As for the woman's mud carapace, "this is a genuinely new discovery in Egyptian mummification," Sowada said. "This study assists in constructing a bigger — and a more nuanced — picture of how the ancient Egyptians treated and prepared their dead."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus