500 million-year-old fossil is the granddaddy of all cephalopods

These tiny creatures existed during the early Cambrian.

The oldest known cephalopod — part of the group that includes octopuses, squid, cuttlefish and nautiluses — is more than half a billion years old, a new study suggests.

The fossils date to the early Cambrian period and are about 522 million years old, according to the researchers, who found the fossils on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada. Until now, the oldest cephalopod on record was a shelled creature known as Plectronoceras cambria, which lived about 30 million years after the recently discovered, yet-to-be-named cephalopod, the team said.

The finding suggests "that cephalopods emerged at the very beginning of the evolution of multicellular organisms during the Cambrian explosion," study lead researcher Anne Hildenbrand, a geoscientist at the Institute of Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University in Germany, said in a statement.

Related: Release the kraken! Giant squid photos

Previously, molecular studies based on rates of genetic change over time suggested that cephalopods originated in the early Cambrian. But the new findings — which "arguably represents the earliest cephalopod known to date" — are the first concrete evidence that supports this idea, the researchers wrote in the study.

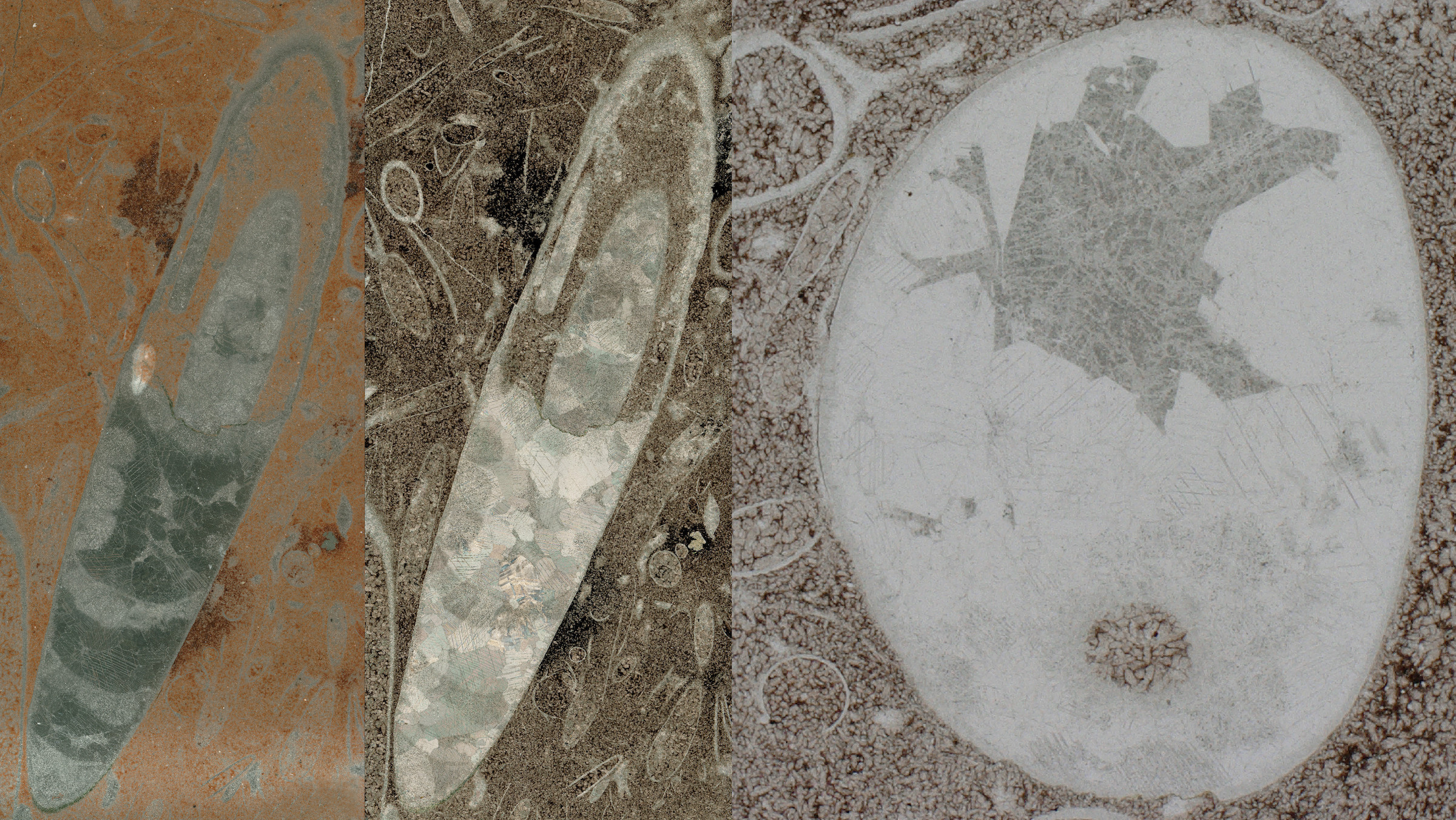

The ancient, pill-shaped cephalopod fossils are tiny — one measured just half an inch tall (1.4 centimeters) and 0.1 inch (0.3 cm) wide, the researchers said. But that's to be expected, because "all of the cephalopod-ish things from back in the Cambrian were pretty small," Michael Vecchione, an invertebrate zoologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

The fossils show that this ancient creature had a cone-shape shell that was subdivided into different chambers. These chambers were connected by a siphuncle — an internal tube seen in shelled cephalopods, including extinct ammonites and modern-day nautiluses — that pumps fluids and gases through the different chambers to help the animal adjust its buoyancy.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By evolving a siphuncle, cephalopods became the first known organisms to be able to actively move up and down in the water, the researchers said. With this ability to move, early cephalopods picked the open ocean as their chosen habitat, the researchers noted.

The researchers discovered the fossils on the ancient micro-continent of Avalonia, which encompassed parts of eastern Newfoundland and Europe. The team hopes to find more fossils of this ancient creature so that they can confirm, with greater certainty, that it's an early cephalopod, they said.

However, based on the data presented in the new study, published online March 23 in the journal Communications Biology, Vecchione said that the team's analysis was on point.

"I think it is a cephalopod based on what they found," Vecchione said. He added that this discovery "means that [cephalopods] separated from the other mollusks really early." Today, mollusks include soft-bodied invertebrate animals such as sea snails, clams and abalones.

"Cephalopods are really different from other mollusks," Vecchione said. Still, "we do know that they're mollusks, they're not from outer space like some people have said."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus